As a young boy in New York, I was bitten by an animal you wouldn’t typically worry much about – a squirrel. I deserved it; having foolishly tried to pick the poor little rodent up by its furry tail. Despite the critter’s small size, though, there was an immense amount of blood spurting out of the wound on my ankle.

When I moved out West, there were bigger and more ominous mammals to worry about. Hiking down a trail in Montana one day, I saw what looked like a large dog heading toward me. As it got closer, however, I saw that it had a very long thick tail. It was a mountain lion. Just a big cat, I figured, and continued walking toward it. My colleagues later informed me that this was probably unwise, because mountain lions attack human beings all the time. I was lucky, though, the big cat turned around and disappeared into woods, and did not later pounce on me from a tree.

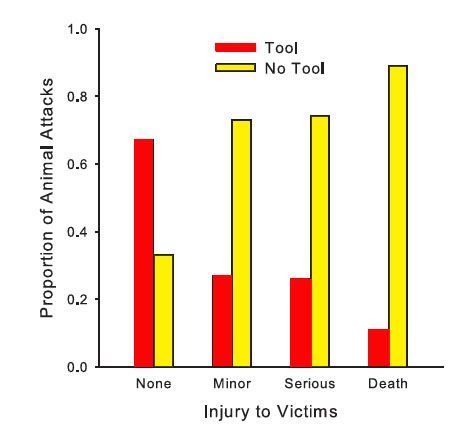

Because I just finished John Vaillant’s brilliant story of a man-eating tiger in Eastern Russia, and because I often go for hikes on trails marked with mountain lion warnings, I was inspired to check online about the actual frequency of mountain lion attacks. I found a list of confirmed cougar attacks in the United States and Canada (in case you live closer to the squirrels in Central Park, cougars, pumas, and mountain lions are all the same thing). I discovered that many of the confirmed cougar attacks happen in British Columbia, where I travel every summer, frequently seeking out remote trails in the mountains. Mountain lions do a lot more damage than squirrels, of course, occasionally killing a mountain biker or someone out for a casual stroll in the woods. But most of these stories have a non-fatal ending. One man in British Columbia used his bicycle as a weapon to drive away a mountain lion that had pounced on him; other folks used knives or rocks to defend themselves. My colleague Peter Crabb collected reports of 542 animal attacks from all around the world, and found that when either the victim or a passerby used a tool to defend against the attack, their odds of walking away alive went up dramatically (see the figure). Guns were used in about 28 percent of the cases; sticks, stones, and knives made up another 25 percent; and the remainder included a wide range of objects from brooms and bicycles to snowballs and telephones.

Of course, if you play by the numbers, you should be much more worried about the other drivers you pass on the way to the trailhead. They are thousands of times more likely to kill you than any of the wild animals you will you encounter. Although at least one Canadian and 2 Americans have been killed by mountain lions since 2001, over 25,000 Canadians, and more than 400,000 Americans have died in automobile collisions during the same period. Most of those deaths are accidents. Add to that the fact that over 200,000 humans have been intentionally murdered by other humans in North America during that same period, and my money says I’m a lot safer out walking in mountain lion country.

Despite my knowledge of those odds, however, I’m still a little nervous about a big cat pouncing on me from the trees when I go for a hike. Why?

I found some answers to these questions in John Vaillant’s The Tiger: A true story of vengeance and survival. Vaillant’s book is one of the most thoughtful, and thought-provoking works of non-fiction I’ve read in some time, one of those books that made me feel as if I was learning something new in every chapter. It combines elements of mystery, natural history, cultural geography, and evolutionary psychology. The center of the story is a Russian game inspector named Yuri Trush. Trush is tracking down a tiger that has killed several people near Primorye, a remote town in the frozen wilderness just North of the Chinese border. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, many of the residents of the area are without reliable sources of income, and they survive partly be poaching wild animals. In two separate incidents, the tiger has killed poachers, and has himself been injured. Now the hungry man-eater’s tracks are coming closer and closer to the village, although he remains elusive. At the book’s end, Trush and his men finally track down the beast, only to have it attack Trush himself. Vaillant paints a vivid picture of this final scene, and it plays out like a movie episode (I won’t ruin it by telling you whether it’s a horror movie or a James Bond episode).

In telling this particular story, Vaillant also paints a vivid anthropological account of another place in the world: a remote outpost of Russian society in which people are much more likely to confront the problems our ancestors faced – not enough food on your own table, and animals that want to eat you for dinner. He delves also into the mind of the tiger, noting that the locals, as well as some of the biologists who study these predators, believe that tigers can hold personal grudges against particular humans, and spare other folks who intend them no harm. Along the way, Vaillant even covers some interesting research from evolutionary psychologists such as Clark Barrett and Joshua New on the ways humans think about animals.

I myself picked the book up because it contained a cover blurb from the eminent field biologist George Schaller (who has himself studied lions and tigers and snow leopards, if not bears). Schaller says: “There have been many tiger books, but none which so deeply try to probe the mind of tigers and the mind and habits of humans living in the same forest.” As luck would have it, I mentioned the book to my friend Mark Schaller, who is George’s son, and who will be my host when I visit British Columbia in a couple of weeks (I have discussed Mark’s research on the behavioral immune system earlier). Mark had not only read and enjoyed the book himself, but he pointed out that Vaillant was one of his neighbors in Vancouver. Perhaps I will try to get Mark to invite John to take a hike with us, down some trail where we can get in touch with our ancestral fears by serving as mountain lion bait. Indeed, we might not need to go very far. Last year a mountain lion showed up in Santa Monica. So given that Vancouver has abundant forests nearby, I shall not be surprised to see one show up on Mark’s porch. I will be sure to carry a broom, a telephone, or some other defensive tool wherever I go.

References.

Crabb, P. B., and Elizaga, A. (2008). The adaptive value of tool-aided defense against wild animal attacks. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 633-638.

Vaillant, J. (2010). The tiger: A true story of vengeance and survival. New York: Knopf.