Sex

Identification of Red-Flag Sexual Grooming Behaviors

A new study sheds light on red-flag sexual grooming behaviors.

Posted March 9, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- A new study identifies red flag sexual grooming behaviors that are significantly more reported in cases of childhood sexual abuse.

- Individuals who experience childhood sexual abuse report twice as many sexual grooming behaviors compared to those who did not report abuse.

- Identification of red flag sexual grooming behaviors can help in the prevention and detection of child sexual abuse.

- Behaviors involving desensitizing a child to physical contact and sexual content were more likely reported by those who experienced abuse.

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a serious global problem; it is estimated that one in four girls and one in 13 boys will experience CSA by the time they reach adulthood. However, the prevention of CSA can be challenging as children frequently do not report CSA, and even if they do, it may be many years after it happened. While there are many barriers to reporting sexual abuse, one of the reasons that children may not disclose the abuse they experience is because the perpetrator used sexual grooming behaviors. As the onus of protecting children lies with parents, guardians, and child serving institutions, new research on the identification of red-flag sexual grooming behaviors can help adults identify high risk behaviors directed toward children in order to prevent CSA before it occurs.

What Is Child Sexual Grooming?

Sexual grooming broadly refers to the behaviors and tactics that perpetrators use to manipulate children, their guardians, and their surroundings to facilitate sexual abuse while decreasing the likelihood of disclosure or detection. It is estimated that up to 99% of all cases of CSA involve some elements of sexual grooming. Our research further broke the process down into five stages described in the content-validated Sexual Grooming Model (SGM).

- Victim Selection

- Gaining Access and Isolation.

- Trust Development.

- Desensitizing the Child to Sexual Content and Physical Contact

- Post Abuse Maintenance Behaviors

A comprehensive description of the stages of sexual grooming and a list of identified sexual grooming behaviors as delineated in the SGM can be found here.

Why Is It Hard to Recognize Sexual Grooming?

While there is increasing public awareness of what sexual grooming means, several studies have found that it is often hard to detect sexual grooming behaviors before the abuse happens. This is because on the surface many sexual grooming behaviors look like normal adult/child interactions and it is only their intent that is deviant. For example, spending time one-on-one with a child and giving them a lot of attention can be vital to developing their self-esteem and psychological well-being. However, someone who wants to abuse a child may use those same strategies so that the child will trust them and value the relationship and thus they may be less likely to report once the abuse occurs. Guardians can also be groomed such that they will overlook warning signs and fail to detect abuse because the perpetrator has become a trusted individual who appears to care for their child.

We have also done research that shows that people may overestimate their ability to detect sexual grooming once they already know that the abuse has occurred. This is known as the hindsight bias – or the “I knew it all along” phenomenon. While there is some evidence that it may be easier to identify sexual grooming behaviors that involve touch, overall recognition rates of sexual grooming behaviors were low.

Red-Flag Sexual Grooming Behaviors

To identify which specific grooming behaviors differentiate normal adult/child interactions from those that are indicative of sexual abuse – also known as “red flag” sexual grooming behaviors — a new study published by our team compared established sexual grooming behaviors reported in cases of CSA that differentiate them from non-abusive adult/child interactions. Specifically, we had 411 adults who had experienced CSA complete our self-report measure of sexual grooming behaviors and then we had a sample of 502 adults who did not report a history of CSA complete a modified version of the self-report measure about an adult male (see the three relationship conditions below) with whom they had the most interpersonal contact and they were randomly assigned to one of three conditions:

- Immediate Family member (parent, sibling, stepparent, step-sibling, grandparent, uncle)

- Non-family member (romantic partner, ex-partner, friend, friend of a friend, acquaintance)

- Community Member (coach, teacher, religious leader, other)

Overall, the results were pretty clear. Individuals who had experienced CSA reported more than twice as many sexual grooming behaviors compared to those who did not experience CSA and there were significant differences between those who experienced CSA and those who did not on 38 out of a possible 42 sexual grooming behaviors. Further there were significant differences between groups for all five stages of the sexual grooming model with those who experienced CSA reporting significantly more sexual grooming behaviors at each stage than those who did not experience CSA.

There were few differences between groups based upon the identity of the adult male (family member, non-family member or community member); however, overnight stays, being affectionate and loving and giving rewards and privileges were not significantly more reported for family members but were significantly more likely to be reported for non-family and community members. This means that these behaviors (overnight stays, being overly affectionate and gift giving) may not be red flags for family members but they are for those who are not family members and for community members.

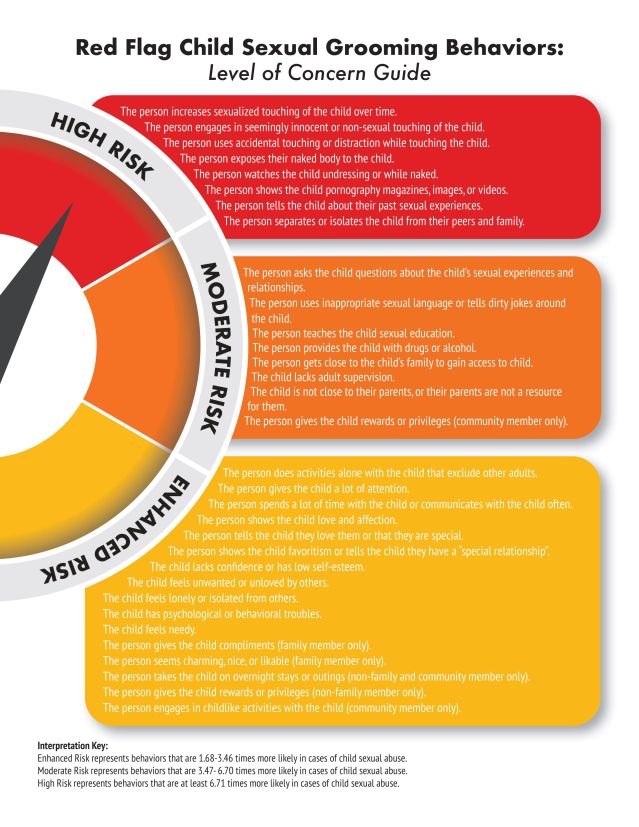

The sexual grooming behaviors that differentiated between the two groups (those who experienced CSA and those who did not) are listed below and can be viewed here. High-risk behaviors represent large effect sizes, moderate risk behaviors represent moderate effect sizes and enhanced risk behaviors represent small effect sizes.

High Risk Behaviors: These behaviors are 8 times or more likely to be reported in cases of CSA. The number in parentheses represents how many times more likely these behaviors were reported in cases of CSA compared to non-CSA.

- The person increases sexualized touching of the child over time (34 times).

- The person engages in seemingly innocent non-sexual touching of the child (8 times).

- The person uses accidental touching or distraction while touching the child (21 times).

- The person exposes their naked body to the child (26 times).

- The person watches the child undressing or while naked (11 times).

- The person shows the child pornography magazines, images or videos (8 times).

- The person tells the child about their past sexual experiences (9 times).

- The person separates or isolates the child from their peers and family (19 times).

Moderate Risk Behaviors: These behaviors are between 3.5-6.4 times more likely to be reported in cases of CSA. The number in parentheses represents how many times more likely these behaviors were reported in cases of CSA compared to non-CSA.

- The person asks the child questions about the child’s sexual experiences and relationships (6.4 times).

- The person uses inappropriate sexual language or tells dirty jokes around the child (5.7 times).

- The person teaches the child sexual education (4 times).

- The person provides the child with drugs and/or alcohol (4.6 times).

- The person gets close to the child’s family to gain access to the child (3.8 times).

- The child lacks adult supervision (5.5 times).

- The child is not close to their parents, or their parents are not a resource for them (3.8 times).

- The person gives the child rewards or privileges (community member only) (4.8 times).

Enhanced Risk Behaviors: These behaviors are 1.8 to 3.4 times more likely to be reported in cases of CSA. The number in parentheses represents how many times more likely these behaviors were reported in cases of CSA compared to non-CSA.

- The person does activities alone with the child that excludes other adults (3.4 times).

- The person gives the child a lot of attention (3.2 times).

- The person spends a lot of time with the child or communicates with the child often (1.8 times).

- The person shows the child love and affection (1.9 times).

- The person tells the child they love them or that they are special (3 times).

- The person shows the child favoritism or tells the child they have a “special relationship” (2.6 times).

- The child lack confidence or has low self-esteem (3.1 times).

- The child feels unwanted or unloved by others (3.4 times).

- The child feels lonely or isolated from others (2.3 times).

- The child has psychological or behavioral troubles (2.6 times).

- The child feels needy (2 times).

- The person gives the child compliments (family member only) (2 times).

- The person seems charming, nice, or likable (family member only) (1.8 times).

- The person takes the child on overnight stays or outings (non-family member and community member only) (2.7 times).

- The person gives the child rewards and privileges (non-family member only) (1.8 times).

- The person engages in childlike activities with the child (community member only) (2.7 times).

Given that the post-abuse maintenance behaviors occur after the abuse has already happened, we found that these behaviors were reported by adults who experienced CSA between 3 and 57 times more than those who did not experience CSA.

The findings of this study represent a big step forward in the identification of red-flag sexual grooming behaviors and have significant implications for the prevention, detection, and prosecution of CSA.

For a full copy of the research study click here and a copy of the infographic of red-flag sexual grooming behaviors can be accessed here.

References

Jeglic, E., Winters, G.M., & Johnson, B.N. (2023). Identification of red flag child sexual grooming behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 136 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105998

Winters, G.M., & Jeglic, E.L. (2022) Sexual Grooming: Integrating Research, Practice, Prevention, and Policy. Springer