Positive Psychology

When Demographics Aren't Destiny

Most people falsely believe positive outlooks indicate privileged backgrounds.

Updated December 28, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Approximately 1,000 researchers and non-researchers predicted whether worldviews reflect privilege.

- They predicted that the rich would see the world as much more abundant, men would see the world as safer, etc.

- Yet large studies of more than 15,00 people found that all their predictions were wrong.

- This is good news: Positive world beliefs may be key to well-being yet aren't determined by privilege.

Many people today are realizing how demographics—such as sex, income, neighborhood affluence, and crime—can shape success and happiness. This awakening is a positive step. Yet a new study also reveals a major way that demographics are not destiny, contradicting what hundreds of researchers, including my own research team, predicted.

Primal World Beliefs

People hold beliefs about all sorts of things, from politics to family and more. Since 2019, psychologists have studied a special type that researchers call primal world beliefs, or “primals” for short. Primals describe people’s most basic beliefs about the character of the world as, essentially, one whole, huge place.

People have lots of different primals. Take a hundred people on the street and you’re bound to find some who view the world as safe and some who see it as a battleground (that's one dimension of primals, called "safe world belief"); similarly, some will consider it a barren desert and others think the world is overflowing with abundance (that's "abundant world belief"). Researchers know of 26 dimensions. Most boil down to the belief that the world is usually a good, wondrous place or a bad, miserable place.

Primals matter. A 2022 study showed that positive primals are strongly correlated to many positive outcomes, including well-being (which correlated at around .60, the same correlation as that between Earth's surface temperature and distance from the equator). Much existing theory (like that underlying cognitive behavioral therapy) suggests a chunk of this covariation is causal, and research exploring that possibility continues.

Yet we wondered: Could living an easy, privileged life drive both positive outcomes and positive primals?

Maybe positive worldviews are super great for the rich, for men, and for healthy folks living in safe and wealthy neighborhoods and strolling through life trauma-free, but not for the less privileged among us. To paraphrase a study subject:

"I wish I could see the world as abundant, but I grew up poor, and that's just not in the cards for folks like me."

If primals are indeed mirrors that reflect our backgrounds then, if I know your primals, I know your background. Maybe people who see the world as abundant, for example, have truly experienced more abundance; and people who see the world as more dangerous have been through more danger; etc.

So we ran another set of studies, recently published in the Journal of Personality, exploring the connection between primals and privilege

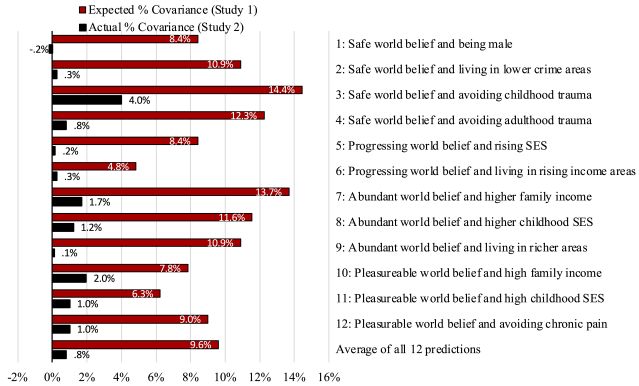

We started by asking about 500 professional psychologists and about 500 non-academics to predict the strength of 12 correlational relationships between specific primals and specific indicators of privilege (not including race, unfortunately, due to potential confounds, but that is also being looked into).

They predicted substantial relationships. For example, they thought that men should see the world as much safer than women; people in high-crime neighborhoods should see the world as more dangerous; poor people should see the world as more barren; residents of rich neighborhoods should see the world as more abundant; and so forth.

Then, we ran several large studies (involving ~14,500 people) to determine actual relationships.

The Results Were a Big Surprise

Not one prediction was correct or even close (see figure below). The prediction least wrong was 3.5 times bigger than the actual relationship (between childhood trauma and the belief the world is dangerous), and, on average, predictions were 12 times too big (r-squared of .8 versus 9.6).

Because we were so surprised, we did another study of ~1,000 more people finding, for instance, that even people suffering from terrible illnesses (cancer and cystic fibrosis) didn't see the world more negatively (bad, dangerous, or unjust) compared to control groups.

What Do the Findings Tell Us?

In one way, not much. Just knowing the correlation between primals and privilege is unsatisfactory. A deeper understanding will require longitudinal and experimental research.

Yet a reasonable takeaway is that making life more abundant is unlikely to greatly increase abundant world belief, making life safer likely won't greatly increase safe world belief, and so forth. This is consistent with another study that showed that when the pandemic made the world objectively more dangerous, dangerous world belief did not go up.

But the much bigger takeaway here is the big and consistent gulf between prediction and reality. When it comes to primals, we thought demographics would be destiny, and we were wrong.

Instead, Primals Are Hidden

For me, this study hammered home the point that humans are really bad at guessing people's primals. Past research shows, for instance, that intuitions can be wrong about the primals of successful people and the primals that separate the political left from the right.

- This means we can’t see someone on the street and make good guesses about their primals.

- This means many of us are probably wrong about the primals of people we know well. True story: I (a primals expert) couldn't guess the primals of some of my own family members. For me to find out my mother's primals, she had to take the same scientifically-validated survey as everyone else and send me her results.

- This means if you do learn someone's primals, you can't assume much about their background. For example, if I see the world as more dangerous than you, it'd be reductive and wrong to assume that's because I've experienced more danger than you.

- This means many of us are wrong about where our own primals come from. We tell ourselves stories—that we see the world like we do because of our experiences of poverty, etc.— that can't all be true.

- This means that seeing the world negatively out of a sense of solidarity with those less fortunate might be misguided.

What's the Good News?

Maybe we aren’t stuck. These findings do not mean primals can’t change. It only means that many experiences outside of our control likely don't shape our primals in an inevitable, reductive way.

For instance, my research team is exploring possibilities that (a) the things we pay attention to and (b) exposure to people in our lives with very different primals can shape primals. But whatever determines our primals appears to transcend the indicators of privilege and hardship measured in this study.

Considering the well-established link between positive primals and well-being, it’s a good thing. For many of us, viewing the world more positively may not be out of reach.

References

Kerry, N., White, K. C., O'Brien, M., Perry, L., & Clifton, J. D. W. (2023). Despite popular intuition, positive world beliefs poorly reflect several objective indicators of privilege, including wealth, health, sex, and neighborhood safety. Journal of Personality. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12877

Clifton, J. D. W., & Meindl, P. (2021). Parents think—incorrectly—that teaching their children that the world is a bad place is likely best for them. Journal of Positive Psychology, (17)2, 182-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.2016907

Clifton, J. D. W. (2020). Testing if primal world beliefs reflect experiences—At least some experiences identified ad hoc. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01145

Clifton, J. D. W., & Kerry, N. (2022). Belief in a dangerous world does not explain substantial variance in political attitudes, but other world beliefs do. Social Psychological and Personality Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221119324

Lansford, J. E.,... (2023). Development of Primal World Beliefs. Human Development 2023; https://doi.org/10.1159/000534964

Ludwig, V. U., Crone, D., Clifton, J. D. W., Rebele, R. W., Schor, J. & Platt, M. L. (2022). Resilience of primal world beliefs to the initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Personality. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12780