Animal Behavior

Do Turtles Play?

Our human view may be too narrow.

Posted April 30, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- An old tale helps redirect our view of play.

- Play may not be a talent and a pleasure reserved only for warm-blooded mammals like us.

Here’s a story that recruits ancient folklore, Bugs Bunny cartoons from the 1940s, and leading-edge animal behavior science to tell a tale about the deep history of play.

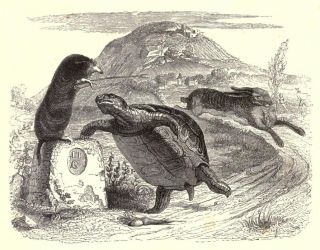

It begins with Aesop, the fabulist, possibly a real person who may have lived in ancient Thrace, who left us a series of catchy paragraph-long fables that often feature talking animals. Each of these carries a simple, memorable moral. Nearly three millennia later, the stories still circulate.

Slow but Steady Wins the Race

We are best familiar with Aesop’s amusingly twisty “Tortoise and the Hare.” In that tale a fox arranges a footrace between a rabbit and a reptile. The rabbit should win, of course. He’s amazingly fleet of feet, after all. But he’s also unbearably mouthy, impulsive, overconfident, and lazy. He’s poised for a comeuppance. Not long after leaving the plodding terrapin eating his dust, and bored with the contest, the odds-on favorite stops for a nap. Meanwhile, the tortoise plods intently ahead and crosses the finish line just as the outraged bunny wakes up.

The moral, as the translator Francis Barlow rendered it in verse in 1687, “Mean parts by Industry have Luckyer hitts/ Than all the fancy’d Power of Lazyer witts.” Or as we would put it more directly today, “slow but steady wins the race.”

Bugs Bunny and Cecil Turtle Revive the Old Tale

I came to know the tale by watching Saturday morning cartoon reruns. Some of these pitted Bugs Bunny, the very model of the American trickster, against the slow-moving but, as it turns out, not so slow-thinking Cecil Turtle.

Ready with wisecracks delivered in his cheeky Flatbush accent, Bugs Bunny, like his predecessor, is asking for it. In the first of three Warner Bros. variations on Aesop’s tale, Tortoise Beats Hare (1941), Bugs vastly underestimates his slow-moving opponent, who enlists nine of his turtle cousins to station themselves ahead and along the race’s path. The last lookalike co-conspirator lounges unaccountably at the finish, ready to share his $10 winnings from the breathless rabbit. Bugs loses a rematch in a more whiz-bang animated short, Rabbit Transit, (1947). But this time Cecil has concealed rockets in his shell. It’s not with persistence like the tortoise of old that he challenges Bugs Bunny but with brains and blinding speed. (Spoiler alert: Bugs crosses the line first but loses in the end as a traffic cop hauls him off to jail for speeding.)

In these cartoons, Cecil Turtle not only outsmarts the smart alec but he outpaces him. And this brings us to the modern, scientific, surprising, story of the speeded-up turtle.

A Warm-Blooded Bias?

A sidebar. I have casually observed the same gopher tortoise, the only native North American reptile of his kind, from a perch above a southeastern beach every year for the past three and a half decades.

Over this long interval, he has endured a beach fire, three hurricanes, and a couple of suspected tornadoes. Otherwise, nothing much outside of occasionally flinging sand from his burrow and basking in the afternoon sun seems to punctuate his days. No Shaolin monk has ever zzzzzed so serenely. Oh, once I witnessed a slo-mo wrestling match with an invader who was eventually overturned. I was tempted to say that the interloper was “chased off.” But that would have vastly speeded up the action.

I might be forgiven for this unsympathetic choice of words. (We warm-blooded mammals last shared a common ancestor with reptiles some 250 million years ago.) But it may not be our lack or armor, our warm blood, or our comparatively feverish movements that condition our opinions. It may be the vastly different time-scale we and the gopher tortoises live by.

As a result, when it comes to observing play among them, we mammals may be selling turtles and their cousins, tortoises, short.

An Egyptian Turtle at High Speed

Here’s the twist. More than a decade ago, the eminent evolutionary biologist and ethologist Gordon Burghardt told me that he had videos of an Egyptian aquatic Nile turtle that could play. Thinking that warm blood and a cognitively sophisticated brain were prerequisites for play, I suspected that his perception of a playful turtle was a version of confirmation bias. After all, once you deeply examine a subject, you are likely to see evidence of it everywhere. And again, because of the evolutionary distance, how could we even hope to get inside the mind of a turtle to understand its alleged impulse to play?

Identifying Play

Burghardt had plausibly proposed that play (always hard to define) can instead be identified by five basic criteria—that the behavior is not functional per se, that the activity must be pleasurable and often spontaneous, that it differs from serious behaviors, that it is not abnormal (like compulsive rocking or pacing), and that it starts without stress. And his turtle seemed to fit these criteria as it bobbed about bumping into a ping pong ball and a hoop that floated with him.

Still, I remained a skeptic. But a mischievously simple demonstration had me ready to believe. Burghardt sent me two videos of the turtle interacting with the ping pong ball. The first, again, seemed random. But he sent me a second speeded-up version. In this view, more accommodating of a human time scale, the turtle seemed to be dribbling the ping pong ball—chasing it, dodging it, nudging it purposefully and playfully.

Burghardt’s schema opens play broadly to other species. Thus, he notes that fish leapfrog. Komodo Dragons bat around old shoes and play tug of war with their keepers. Stingrays nudge floating objects and seem to compete for the pleasure. Poison dart frogs wrestle. Vietnamese mossy tadpoles ride bubbles. Saltwater crocodiles play with basketballs. And so on.

Seeing these behaviors as play requires only a little adjustment and a minor suspension of mammalian disbelief. Apparently, I had been suckered into an underestimation as basic as Bugs Bunny’s misreading of the rocket-powered Cecil Turtle!

The Moral of the Story

Look carefully and cleverly enough and you may find play everywhere there is life on Earth.

References

Gordon M. Burghardt, The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits, (2005).

Gordon M. Burghardt, “The Comparative Reach of Play and Brain: Perspectives, Evidence and Implications,” American Journal of Play, vol. 2., no. 10, (2010).

Gordon M. Burghardt, “Play in Fishes, Frogs, and Reptiles,” Current Biology, vol. 25, no. 1, (2015).