Trust

How Robinson Crusoe Managed His Man Friday

The castaway was an intuitive game theorist – just like your dad.

Posted February 9, 2014

Robinson Crusoe was stranded on a desert island. He behaved as if he were the only person on the island until one day he discovered a footprint on the sand. From that moment he realized that he was not playing against nature anymore. He was facing rational opponents. ~ G. Tsebelis (1989)

When Robinson Crusoe discovered his cannibal neighbors, his perspective on life changed. He realized that he had to act strategically. When he saved Friday from becoming the cannibals’ dinner this change came home. He was no longer alone; he had human company. This he had wanted for so long, but when he had the chance to get it, it frightened him. How would he relate to another human being who had a phenomenally different cultural background? Would he, in fact, have to fear for his own life? It would not have been the first time that the saved kill their saviors. Those of us who have read Daniel Defoe’s masterly novel (and those who remember Hollywood’s various rehashes) know that Crusoe and Friday got on well with each other, mostly. They solved, it seems, some of the elemental challenges of human interdependence. It is remarkable that these two fictional characters did not carnivorate each other within the first year.

In their new book on social dilemmas, Paul van Lange and his co-writers (2014, p. vii) note in their preface that “even the literary character, Robinson Crusoe, must have quickly learned about social dilemmas after Friday entered his life.” Yes! But then, agonizingly, van Lange et alii move on without telling us what Crusoe was faced with and how he prevailed in a difficult situation. So, Paul et alii, I’ll have to do the job for you. Here goes.

The appearance of Friday poses a problem for Crusoe inasmuch his preferences are not perfectly aligned with Friday’s (eurocentrically, we begin by taking Crusoe’s perspective). Crusoe has a choice between two strategies. He can be harsh and lord if over the savage, banking on his superior firepower and the savage’s assumed sense of gratitude. He can also be gentle, hoping that nice guys finish first and knowing that niceness takes less effort than harshness. Crusoe’s situation requires him to consider Friday’s options as well. Friday has a choice between submission and rebellion. He might submit out of gratitude or fear, and he might rebel out of pride, greed, or a sense of fairness.

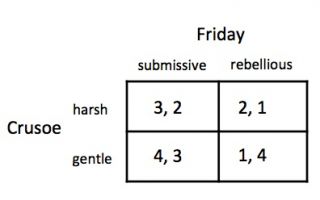

Having 2 people in play, each with 2 strategies at their disposal, yields 4 potential outcomes for Crusoe to contemplate. Let us make an educated guess as to how Crusoe might rank these outcomes. Arguably, Crusoe would most like to be gentle with a submissive Friday. That would be nice and convenient. If this outcome is not attainable, Crusoe would be harsh with a submissive Friday. Next, he would be harsh with a rebellious Friday, and his least preferred outcome would be gentle with a rebellious Friday. This outcome would signal his undoing or enslavement. Stated differently, Crusoe’s primary wish is for Friday to be submissive rather than rebellious. His secondary wish is reciprocation. He would respond to submission with gentleness and to rebellion with harshness.

Friday has his own preferences. He would most like to rebel against a gentle Crusoe and become master himself. Next, he would settle into a submissive role with a gentle Crusoe. Submitting to a harsh Crusoe would be worse, and – futilely – rebelling against a harsh Crusoe would be the worst scenario. Stated differently, Fridays’s primary wish is for a gentle Crusoe. His secondary wish is contrarian. He would respond to harshness with submission and to gentleness with rebellion.

Now, let us suppose the ranked preferences of the two are as clear to them as they are to us. The matrix displayed in the margin summarizes what we know. Within each of the four cells, the number to the left of the comma is the row player’s (Crusoe’s) preference rank (larger numbers are preferred to small numbers), and the number to the left is the column player’s (Friday’s) preference rank.

Now we are ready to play, using the rules of Steven Brams’s Theory of Moves (Brams, 2011). As Crusoe, we might leer at the lower left cell of the matrix with our preference of being gentle with a submissive Friday. That’s 4 points for us and 3 for him. We notice, though, that Friday would have an incentive to rebel, which would give him 4 points, while reducing us to 1. In response, we, Crusoe, would become harsh, moving from the lower right cell to the upper right. Now, we have 2 points, while Friday is left with 1. In turn, Friday would submit, improving his take from 1 to 2 and ours from 2 to 3. Now we are in the upper left cell of the matrix, and unfortunately, this is not an equilibrium. We, Crusoe, have an incentive to slip into gentleness, which would give Friday an incentive to rebel – and round we go ad infinitum and nauseam.

But this is not what happens in the novel. Perhaps our preference rankings are wrong, or either Crusoe or Friday understood the threat of an infinite cycle of harshness, submission, gentleness, and rebellion. Crusoe, for example, could have refrained from moving from harshness to gentleness while Friday was submissive, knowing that Friday would turn to rebellion. In turn, Friday could have refrained from rebellion when Crusoe was being gentle, knowing that Crusoe would respond harshly. Put together, these two sets of over-the-horizon perspectives would keep Crusoe and Friday on the left side of the matrix.

There is still a critical asymmetry between Crusoe’s and Friday’s perspective. Crusoe can contemplate a potentially destabilizing move from harsh/submit to gentle/submit with the goal of improving the well-being of both players. Friday, however, can make his destabilizing move from gentle/submit to gentle/rebel only with an overall loss of well-being, which, in turn, Crusoe knows. To the extent that over time, the two came to an understanding of their interdependence, Crusoe’s social dilemma turns into a trust game. He can move from harshness to gentleness, trusting that Friday would not betray him and miss the opportunity of having an overall agreeable outcome. The way Defoe tells it, Friday was trustworthy and both he and Crusoe made good.

It seems to me that the Crusoe – Friday dilemma is a general one. You can find it in social situations involving a power differential where neither the ruthless exercise of that power nor stubborn rebellion solves the dilemma (think about your dad and yourself). You might complain that in my analysis the more powerful party reaps the higher payoff in the end. The existence of the power differential entails this result. If you define the differential away by putting a cell into the payoff matrix where both parties get what they want the most, you have solved the problem by denying it, and what kind of a solution is that?

A close reading of the text shows that Defoe lets Crusoe worry about the possibility of rebellion. At night, he withdraws into an inner enclosure that Friday cannot breach without making a noise. With time, however, Crusoe realizes that “I needed none of all this precaution; for never man had a more faithful, loving, sincere servant, than Friday was to me” (Dover edition, p. 153).

See here for Crusoe on happiness and morality and here for another application of game theory in this blog.

For a discussion of the interplay of power and trust, see Krueger & Evans (2013).

Brams, S. J. (2011). Game theory and the humanities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Defoe, D. (1998/1791). Robinson Crusoe. Mineola, NY: Dover.

Krueger, J. I., & Evans, A. M. (2013). Fiducia: Il dilemma sociale essenziale / Trust: The essential social dilemma. In-Mind: Italy, 5, 13-18. http://it.in-mind.org/article/fiducia-il-dilemma-sociale-essenziale (published in Italian and English)

Tsebelis, G. (1989). The abuse of probability in political analysis: The Robinson Crusoe fallacy. The American Political Science Review, 83, 77-91.

Van Lange, P. A. M., Balliet, D., Parks, C. D., & Van Vugt, M. (2014). Social dilemmas: The psychology of human cooperation. New York: Oxford University Press.