Psychology

Psychological Science Needs to Take Off Its Orientalist Lens

As psychologists, we often do not explore the gaps in cultural knowledge.

Posted July 15, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Close your eyes and think of an idealized version of yourself. Do you envision a content, happy person, who is independent and efficacious? This is the positive psychological framework of an individual. Positive psychology aims at maintaining and advancing individual, psychological health. This was a major shift from the disease model of the human mind prevalent in then-psychology. Seems vital enough, doesn’t it? To understand the human mind, we must understand and promote what makes it healthy and not just figure out and avoid what makes it unhealthy.

Positive psychology propels towards strengthening four basic traits — optimism (glass is half full), subjective well-being (how is my quality of life?), happiness, and self-determination (am I competent and independent enough?). These overarching goals, however, are largely based on a Western, individualistic pursuit of a perfect life. Yet the self is not always individual-centric. There exist varied interpretations of the self, with respect to emotions, morality, and temperaments across different cultures. In fact, these interpretations often contrast Western perspectives vividly.

Now, think about the East. What, in your opinion, constitutes the sense of self in Eastern countries (apart from what is shown in say, Miss Saigon or Memoirs of a Geisha)? Academic psychology is also interested in understanding cross-cultural differences of the human mind. However, most reported differences in what is observed in the West versus the East lacks nuance and context. For instance, such a difference is often described in binary terms (e.g., individualism versus collectivism). Academic, and therefore popular understanding of the Eastern mind is rooted in Otherization, while scant attention is paid to social contexts with roots in history, especially colonial history.

Postcolonial theories provide a critical lens to understand such a social context. For example, a key term in understanding how the West views the East is Orientalism. In simple terms, Orientalism is the colonial practice of creating, justifying, and prescribing certain characteristics onto the colonized. European colonizers often believed that the occupied colonies were in dire need of Western, modern civilization. In fact, the rationale for colonization was purported to be the "civilizing mission," implying that colonies comprise inferior, barbaric savages in need of saving.

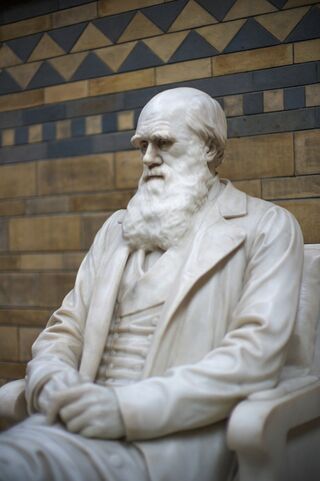

It is extremely important to understand the impact of this regimented thought. Western academia observed the colonized through Orientalism. Hence, academics perceived the Other through an unconscious notion of inferiority and incorporated the same thinking process amongst the local colonized population. This understanding was not an outcome of conscious politically-motivated biases. They were writing at a time when dichotomies such as science versus belief were furnishing. Hence, they strongly believed that their observations were based in scientific inquiry, free of ideological biases.

With the advent of cross-cultural studies in a (largely) postcolonial world, the late 20th century saw a shift in psychology. Not so much in the Orientalist attitudes directly, but the language associated with the Other. Now, the latter was defined in terms of the ‘Third World.’ Academics from these ‘First World’ countries aimed at replicating social and cultural experiments amongst the non-Western population. To cement its place as a serious scientific discipline (as defined by modern, western principles), psychology adapted the scientific principle of generalization — concepts and principles developed are replicable to an exacting degree in all contexts. Therefore, hypotheses simply need to be exported and the results compared. This blatant lack of acknowledgment of cultural demands has only recently been challenged.

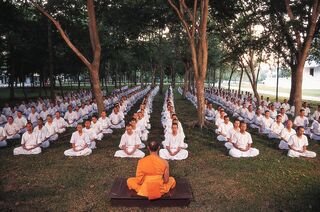

This has led to a growing interest in ‘indigenous’ explanations of psychological principles, some of which propagate the postcolonial ideas of the ‘exotic’ and the ‘mystic.’ For example, research has looked at Buddhist-derived interventions (BDIs) in different clinical settings. These are modeled around tenets of Buddhist belief — wisdom, meditation, mindfulness, non-self, non-attachment, compassion, and ethical decision, among others. However, there has been some degree of confusion regarding the appropriate transmission of these principles to the western cultural setting. Hence, the perspective that the aforementioned principles are inherently ‘mystical’ and aimed at ‘spiritual development’ remains.

In recent times, the practice of mindfulness, specifically, has found its way into positive psychology. Upon assessment, this practice has resulted in psychological and physiological betterment. However, cramming such practices into a tradition vastly opposite to them, automatically decontextualizes said practices, thereby establishing the mystical Other. Although this recent movement in psychology recognizes the viable impact of ‘indigenous’ practices on individual well-being, their unchallenged acceptance lies in the degree of submission into the Western model of psychology. By labeling such concepts and practices as ‘indigenous,’ the language automatically creates a covert perception of the non-western (inferior) and non-modern (primitive) Other.

It is becoming increasingly important to question dogmas guiding theories that are established and taught. However, it is equally important to argue that as all traditions, Eastern conceptualizations of the human mind (and Eastern societies in general) are not without flaws. Deeply embedded within these schools of thought also lie discriminatory practices, such as caste in India. Hence, future academics need to be wary of contextualizing interpretations — exercising caution before we create, justify, and prescribe certain characteristics (such as the collectivist mind) to this historical Other.

This post was written by Yarshna Sharma and Arathy Puthillam. Yarshna Sharma is a postgraduate student, pursuing her MSc in clinical psychology. You can get in touch with her here. Arathy Puthillam is a research psychologist at Monk Prayogshala, India. Her research focuses on social, moral, and political psychology. She tweets @WallflowerBlack