Attention

How Eye Contact Brings You Together (or Pulls You Apart)

Mutual glances signal everything from interest to confrontation.

Posted September 11, 2016

In a social situation, eye contact with another person can show that you are paying attention in a friendly way. But it can also be antagonistic, such as when a political candidate turns toward their competitor during a debate and makes eye contact that signals hostility. Here's what hard science reveals about eye contact:

Eye contact can be a friendly social signal. We know that a typical infant will instinctively gaze into its mother’s eyes, and she will look back. This mutual gaze is a major part of the attachment between mother and child. In adulthood, looking at someone else in a friendly way can be a complimentary sign of paying attention. It can catch someone’s attention in a crowded room. "Eye contact and smiles" can signal availability and confidence, a common-sense notion supported in studies by psychologist Monica Moore.

Biological factors behind eye contact are being investigated. As I recently reported, neuroscientist Bonnie Auyeung from the University of Cambridge found that the hormone oxytocin increased the amount of eye contact from men toward the interviewer during a brief interview when the direction of their gaze was recorded. This was also found in high-functioning men with some autistic spectrum symptoms, who may tend to avoid eye contact. Specific brain regions that respond during direct gaze are being explored by other researchers, using advanced methods of brain scanning.

It can also be aggressive. If you watched the recent presidential primary debates, you saw that two speakers turning toward each other can accompany an aggressive argument. When it’s inappropriate, like from a stranger on a city street, steady eye contact can appear threatening.

With the use of eye-tracking technology, Julia Minson of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government concluded that eye contact can signal very different kinds of messages, depending on the situation. While eye contact may be a sign of connection or trust in friendly situations, it's more likely to be associated with dominance or intimidation in adversarial situations. "Whether you're a politician or a parent, it might be helpful to keep in mind that trying to maintain eye contact may backfire if you're trying to convince someone who has a different set of beliefs than you," said Minson.

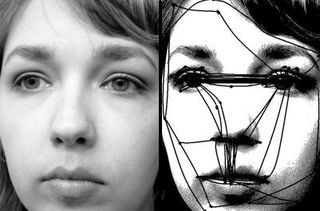

Eye fixations are brief. When we look at a face or a picture, our eyes pause, or fixate, on one spot at a time, often on the eyes or mouth. These fixations typically occur at about three per second, and the eyes then jump to another spot, until several important points in the image are registered like a series of snapshots. An example of such eye movement is shown in this picture. How the whole image is then assembled and perceived is still a mystery although it is the subject of current research.

These jumping or saccadic eye movements are governed largely by a part of the brain called the frontal eye field, located near the prefrontal cortex, a region important for directing attention as well as several other functions.

Personality can modulate how a person reacts to eye contact. In people who score high in a test of neuroticism, a personality dimension associated with self-consciousness and anxiety, eye contact triggered more activity associated with avoidance, according to the Finnish researcher Jari Hietanen and colleagues.

"Our findings indicate that people do not only feel different when they are the centre of attention but that their brain reactions also differ. For some, eye contact tunes the brain into a mode that increases the likelihood of initiating an interaction with other people. For others, the effect of eye contact may decrease this likelihood," Hietanen explained. The study compared brainwave activity from left and right sides of the frontal lobes to infer positive or negative emotions.

A more direct finding is that people who scored highly for negative emotions like anxiety looked at others for shorter periods of time and reported more comfortable feelings when others did not look directly at them.

That may be a reason why, in traditional psychoanalysis, the client lay on a couch and did not face the analyst. It may also contribute to feeling more comfortable when others are looking at an image along with you, a movie or video screen for example, rather than directly at you.

Looking at cell phones threatens real conversation. “Stop Googling. Let’s Talk,” wrote MIT professor Sherry Turkle in the New York Times. It's in real conversation, she wrote, “where we learn to make eye contact, to become aware of another person’s posture and tone, to comfort one another and respectfully challenge one another—that empathy and intimacy flourish. In these conversations, we learn who we are.”

In her book, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, she attributes a 40 percent decline in empathy among college students after 1990 in part to cell-phone screens substituting for face-to-face conversation. This doesn't prove a cause-and-effect relationship, but looking at screens instead of people is certainly a factor. With people so often looking down at phones during a conversation, eye contact can be an even more powerful way to communicate with others.