Behaviorism

The New Skinner Box: Web and Mobile Analytics

We are all now part of the greatest behavioral experiment in history.

Posted March 18, 2014

A couple of years ago, I had the pleasure of speaking on “The Attention Drug Wars” panel at South by South West (SXSW). The discussion centered on how successful social media companies like Facebook and Instagram are able to capture and keep our attention for as long as possible by tapping into the evolutionary reward systems in our brains. While it’s no secret to anyone that a web engineer’s job is to do whatever it takes keep you on their site, few individuals are aware that their methods are founded in the classic operant conditioning experiments conducted by BF Skinner. Skinner put rats in a cage and varied the type, amount and timing of rewards to reinforce different types of behavior. He found that when he manipulated the rats’ schedule such that rewards came at random times, the rats became more engaged and attentive so that they would not miss an opportunity to receive the much-anticipated reward. But his findings hold true for humans as well. For example, it is precisely this phenomenon that allows casinos to make most of their money from slot machines.

The New Skinner Box

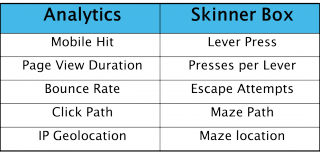

The same rules apply on computer and mobile-based social media sites. This table presents some of the variables BF Skinner would manipulate to perform his experiments along with the web and mobile analytics that correspond to each variable. By examining how you proceed through a website and which pages you spend the most time on, companies learn to maximize your engagement in their products or services.

As a researcher who specializes in identifying problematic behavior and inducing positive behavior change through technology, my natural inclination is to welcome our new masters like Google and Facebook because they are capable of collecting an unprecedented amount of data on human motivation, cognition, and behavior. With that said, most people are unaware of the extent of these sites’ powers of persuasion. Each time we log on to Facebook, we are consenting to participate in a massive social experiment that doesn’t require an ethics committee to monitor its adverse effects. It is therefore important for users to be aware of how these sites are designed to engage and reinforce our browsing behavior through evolutionary reward systems.

While no research exists yet on the brain’s response to social media, we can generalize the results of classical operant experiments to help us hypothesize why so many of us obsessively check our social media accounts. As Skinner revealed, when a reinforcer rewards us enough times, we learn to return to it out of anticipation of future rewards. When we post content on Facebook (e.g. a status update), we are primed to monitor how many “likes” or comments our post will yield. The number of likes and comments we receive for our post then reinforces how brilliant, interesting or witty we feel and how much people love us. It is therefore reasonable to assume that you might get a brief burst of dopamine each time you receive positive social feedback on Facebook. However, the true effect may be remarkably more sinister.

Based on what we know about the reward systems in the brain, it is likely that we get an initial dopamine burst when we first log on to Facebook to check how many likes/comments our post has received. If we get the number of likes/comments we anticipated, other neurotransmitters associated with social bonding or esteem may increase, but dopamine levels will not spike again until the next time you log on in anticipation of more positive feedback. If, however, we don’t get the number of likes/comments we want, our dopamine levels are likely to crash. This activates a vicious cycle: a dopamine rush while reward-seeking, followed by a crash when we are disappointed, followed by more reward-seeking. The big problem here is that the reward we get (e.g. a Facebook like) is actually not what we are truly seeking (e.g. a sense of belonging or connectedness to others), but a derivative that mimics the positive feelings we experience as a result of true social rewards. Therefore, the cycle perpetuates even more. As recent research suggests, this may be especially harmful to those with higher levels of social insecurity for whom this cycle could become a never ending negative feedback loop.

So what do we do about all of this? Eventually, like in many of Skinner’s experiments, we may reach a saturation point. If we fail to receive the anticipated reward enough times in a row, we may ultimately determine that the effort is not worth it. Because developers are always 10 steps ahead of us in figuring out how to vary the reward and reinforcement schedule, I am not so optimistic about this in the short-term.

Manipulating Reinforcement

Many great tools exist to capture the amount of time you spend on different websites, and you can apply website blocking software to specific sites. However, these are external applications and not available on all devices. Given that it is in their best interests to keep users on their sites for as long as possible, sites like Facebook and Google don’t make it easy for external developers to make effective monitoring or blocking applications to help people control their activity and time spent on a page. Believe me, I have tried.

However, we have more internal resources available to us than we think. For instance, I am currently working on trying to check my email less. I have found that one of the most effective techniques I can use to curb my habit is to stop myself when my cursor or finger veers towards the icon is to stop myself and ask: “If I open this application right now, how will my life be improved? If I don’t, how will my life be harmed? What is the harm in waiting a few hours to open it?” While it doesn’t always work, it has helped me understand what I am getting out of these applications and what I am not. Most importantly, unlike the rats in BF Skinner’s experiments, I realize I have an amazing amount of control over the outcome of my own personal experiment.