Anxiety

Scary and Unstructured Play Builds Resilience in Kids

Kids don't need to be protected from fear.

Posted May 11, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Unstructured and thrilling play is good for children's development and mental health.

- Kids today are less likely to engage in thrilling and unstructured play and more likely to have anxiety.

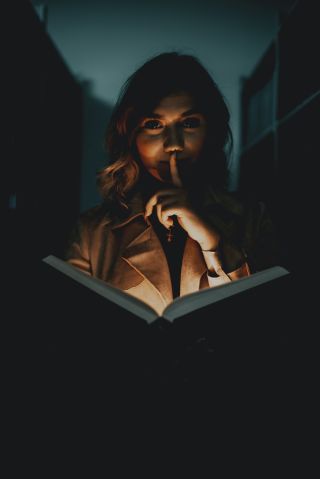

- Scary games, books, and other media offer many of the same benefits as thrilling play.

Play Isn't What It Used To Be

As a kid, I spent a lot of time playing outside. I grew up in a rural area where there was no lack of creeks, forests, canyons, and other places to explore during play. There often wasn’t a purpose to the play; it was just unstructured exploration. This meant I sometimes got a little turned around or found myself in somewhat precarious situations. If I needed to cross a creek, I had to be sure I could make the jump or find a hanging vine that would support my weight to swing across. If I was exploring a canyon, I had to be sure of my footing. As I walked through the forested areas, I had to keep an eye out for snakes or other animals that may not have taken too kindly to my intrusion.

My playful exploration was thrilling, risky, and even a bit scary at times. And it was probably good for me.

Despite it being only about 25 years ago, my childhood experience of play would be pretty atypical for kids who are growing up today. Kids’ independence is increasingly strained by shifting cultural values and concerns over safety. Unsupervised and unstructured play has been on the decline over the past few decades, which means kids are exposed to less adventurous styles of play that lend themselves to thrilling and somewhat scary experiences. Some playful situations that would have been considered perfectly normal 20 years ago are now perceived by some as dangerous.

The Benefits of Thrilling Play

Adventurous and unstructured play is good for kids. When children engage in this type of play, they are exposed to situations that put them on the edge of their comfort zone. Climbing trees, jumping off swings, and exploring unfamiliar terrain keep children right on the line between what they are comfortable doing and what they are a bit afraid of doing. These experiences can sometimes be scary, but they can also be incredibly empowering. As children confront their fears and overcome challenges, they build confidence and resilience to stressful situations.

Despite the evidence that unsupervised, thrilling play is good for children, it has been on the decline for the past few decades. At the same time, rates of childhood anxiety have been on the rise. A child today is over five times more likely to be diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder than they were in the 1950s. This rise in anxiety has been accompanied by decreases in something called locus of control, which refers to the degree that you believe you are in more control of your actions than external factors are.

Psychologist Peter Gray has argued that our society’s decline in unstructured play has left our children less experience in confronting uncertainty and less likely to have a sense of control over their lives. Sense of control is tightly linked with feelings of anxiety, so it seems plausible, even likely, that lower locus of control could be predisposing many children to increased levels of anxiety.

Perhaps one day unsupervised and adventurous outdoor play will be the norm once again. However, what can we do in the meantime to ensure our children are not left without challenging experiences? One possibility is to let your children engage with frightening imaginary worlds.

Scary fiction is well-suited to offer children many of the benefits of risky and thrilling play. Reading a scary book, watching a scary TV show, or playing a scary game presents children with the opportunity to safely face those things that frighten them, the things that challenge their self-efficacy. Scary fictions offer children a productive way to engage with fear and practice those same feelings of uncertainty and anxiety that are present in thrilling and adventurous play.

A Scary Game for Scary Thoughts

Although your parents may have told you that video games are a waste of time, there is some research showing that video games can be good for kids. In fact, scientists have created a video game specifically to help treat anxiety in children.

Any guesses on the genre of the game?

That’s right, there’s a scientifically backed scary game that helps treat anxiety in children.

The Games for Emotional and Mental Health (GEMH) Lab helped create a game called MindLight. The game follows the story of a young boy named Arty who finds himself in his grandmother's mansion. Unfortunately for Arty, his grandmother’s massive house has been taken over by evil, shadowy forces. Playing as Arty, players must bring light back into the house and save Arty’s grandmother. Throughout the house, the players encounter shadowy creatures that block the main objectives. The only way to defeat the monsters is by shining a light on them. Luckily, Arty discovers a glowing hat in his bedroom that can be used to shine light on the monsters, the eponymous mindlight. Sounds easy enough, right?

But of course, there’s a catch: While playing MindLight, players wear an EEG headband that measures brainwaves associated with relaxation. If the player gets too anxious about facing the shadowy monster, the EEG picks this up and sends a signal to the game that dims the mindlight. When the mindlight is too dim, it is no longer powerful enough to defeat the monsters. When the player gets too anxious, they get a visual cue on the screen that helps them calm down and overcome the feeling of anxiety.

Once they reach a state of relaxation, the mindlight begins to shine brightly again and the player is able to defeat the shadowy monster. This also serves as psychological reinforcement, teaching the player that calming down in the face of anxiety and fear is a good way to overcome the thing that made them anxious or fearful in the first place. The game brilliantly utilizes aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT, and neuroscience to help treat anxiety. And this only works because the game is scary.

To learn how to overcome fear and anxiety, children have to experience it. And the best way to experience it is to play with it.

MindLight now has numerous studies reporting on its efficacy in treating anxiety in children. One randomized clinical control trial found that this game was as effective as CBT in both three-month and six-month follow-ups. This is remarkable considering CBT is the gold standard for treating anxiety in children. Another study found that more “approach” behaviors in-game and fewer “avoidant” behaviors in-game were key to the game's power as an anxiolytic. Children who spent more time exploring and facing monsters had even lower anxiety symptoms at follow-ups than children who avoided their fears by hiding in the game.

Children also report that this kind of game is fun, which is more important than it sounds. Although the principles of CBT are scientifically sound, children (and adults, for that matter) don’t always find CBT exercises to be fun. This can lead to reduced engagement with the practices, decreased motivation to learn, and, ultimately, a less effective session. By entrenching these principles in a game rather than in homework, children are much more likely to learn and retain the skills they need to help them deal with anxiety and fear.

Let Them Be a Little Scared

Reading a scary book, watching a scary TV show, or playing a scary game presents children with the opportunity to safely face those things that frighten them, the things that challenge their self-efficacy. Scary fictions offer children a productive way to engage with fear and safely experience feelings of uncertainty and anxiety. Most of the time it’s not the children who are too afraid of scary play — it’s the adults.