Genetics

How Melancholy Comedy Makes Us Happy

Comedy helps us keep our expectations closer to reality.

Posted April 3, 2019

When I was 10, I sported a bushy 70s coif, a la Leif Garrett. The boy-bander with a similarly resplendent do, Shaun Cassidy, I was averse to. Probably because he resembled Kristy McNichol, on whom I had a torrid crush. I grew up in a citadel of heteronormativity, and any hint of jonesing for a dude was dangerously taboo.

But my Leif-y hair and feminine face skewed things. Townsfolk regularly thought I was a girl, before my mom gently told them otherwise. Not that she minded. She said of certain long-locked high schoolers, “He’s too pretty to be a boy.” She meant this positively. She liked the look of her epicene son.

These high school boys played football for my dad, the varsity coach. He was not into pretty boys. He might tolerate them if they blazed like Golden Richards, the balletic blonde receiver for the Cowboys. The coach held his highest praise, though, for the rugged man-boys: Hairy chest. Bristly mustache. Brutal in the trenches. “Much of a man.”

By the time I played for my dad—not as a speedy wide-out but a game-managing QB—I still appeared effeminate, but I didn’t want to. I buzzed my hair short. I hit the weights. I made my dad proud.

That I was pulled between two models of masculinity—the macho man and androgyne—didn’t make me special. Many males mature in confusion. But my rift between biology (a man is a hunter) and invention (a man is what you make him) helped me understand early on: Comedy. Comedy of a certain kind, anyway: irony. The many forms of irony—dramatic, verbal, situational—share a structure: simultaneous signification and de-signification. “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” The famous opening of Pride and Prejudice states and negates: Grammatically, everyone agrees rich men want to get married; rhetorically, woman want rich men to marry them.

The conflict is comic. What you expect is not what you get. This is the structure of funny. Slapstick, where you expect to walk blithely and not slip on the banana. Punning: a word doesn’t mean what you think. “Why shouldn’t you write with a broken pencil? It’s pointless.” One-liners, like Jerry Seinfeld’s: “Proof that we don’t understand death is that we give dead people a pillow.” And self-deprecating one-offs, Dangerfield’s turf: “When I was a kid my parents moved a lot, but I always found them.”

Such is the melancholia of all humor: It reveals the gap between comfort and reality. And such is the glee—of cleverly tricking the “given,” opening to new possibilities for being.

The legislature in my home state lacks humor, as most legislatures do. In 2016, this body voted in favor of the Public Facilities Privacy and Security Act, otherwise known as House Bill Two, or HB2. The most controversial part of the bill, signed into law by then Governor Pat McCrory, forced state schools to match bathrooms with biology. The assumption behind the vote was that gender equals genitalia. This gender vision scorns invention, our ability to construct selves beyond DNA. If I have a penis but identify as a woman, why can’t I be allowed, when nature calls, to behave as a woman? Those opposing HB2 asked this question, to which supporters of the bill might say: What’s to stop you from identifying as an African-American, even though you are Caucasian?

These are philosophical questions going back 200 years, the old debate between essence and existence. Am I given an identity by God or nature? Or do I fashion myself out of my particular historical situation? Both, recent neurology posits. Michael Gazzaniga has demonstrated that the left brain converts the right brain’s raw data into meaningful narratives. Daniel Dennett agrees: We forge our “I” by translating mental impressions into a novel in which we are the protagonist.

As cognitive behavioralists know, these findings are psychotherapeutically valuable: A person clinically depressed can live into narratives more conducive to health. But this interplay between essence—what shapes you—and existence—what you forge—goes beyond mental health to comedy’s joie de vivre.

Place your biology in comic dialogue with your inventions. Your penis and your desire for androgyny. One gently antagonizes the other, revealing its limitations and its virtues. Do the same with your vexed brain chemistry: Maybe you are bipolar (as I am) and you hope for a more harmonious identity. You can’t deny your mind, but you can tease it. You can’t achieve unity, though you can celebrate the striving.

This dialectic is Socratic. Socrates in the agora asks some cocksure philosopher what justice is. Socrates wants to know, because he knows nothing. (So he pretends, playing the straight man.) The interlocutor gets going, confident he can get it right. (He wants to be the banana man.) The more he pushes for certainty, though, the more Socrates, through baiting questions and gentle mockery, demonstrates that his partner is ignorant and that he himself understands substantially. But Socrates—now funny and straight at once—isn’t out to conclude. He wants to keep the conversation going. It is invigorating, joyful.

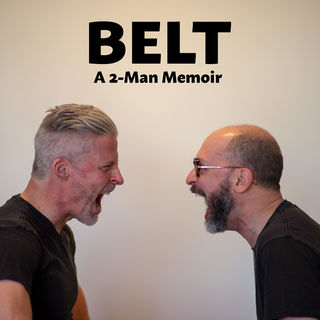

I used to write books on my subjectivity: What does it mean to be me as a man? Like one of Socrates’s marks, I thought, if I am serious and rigorous, I can eyeball my “I.” Now I turn myself into a dialectic between essence and existence. Or I find a friend: Joel Tauber, who is combative, witty, and shorter than I am. I take a position, he exposes its limitations, I do the same, he ridicules my blindness, I riff on his own biases, I laugh at myself, we laugh at each other, and on it goes, the vitalizing et cetera of generous improvisation. We mostly entertain: What does it mean to be a man? Circumcised, I as a teenager first saw an uncut penis, and that made me feel weird, and what did it mean? When I first had sex, I ejaculated before intercourse even began. It still haunts me. I am 52 and recently divorced. Do I now need to man-groom?

Vulnerable is what I am when thinking about these charged instants—even more vulnerable when Joel presses me to go deep inside, where the fear and desire are. The comedy lightens, though. It maintains the dialogue between serious neurosis and humorous self-effacement.

Gambol between evolution and intention. Scorn yourself into felicity. Break-down your manhood, to be a better man.

To hear this rough-and-tumble therapy in action, check out my new podcast with Joel Tauber, https://belt.live