Coronavirus Disease 2019

A Better Way to Stop COVID-19

How to fix public health messaging that's off-target.

Posted May 17, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

We have no vaccine and no cure for COVID-19, and don’t really know when to expect a vaccine or cure, so the only weapon in our fight against COVID-19 right now is our behavior.

But lockdowns and social distancing, two key behaviors necessary to combat the virus, are losing support, so our only weapon—behavior—is fast losing its edge.

For example, all but two states are beginning to re-open, despite failing to meet federal criteria for doing so. According to Unacast, who tracks and grades social distancing through mobile position data in the U.S., only five states get above a grade of “D” for residents in public spaces keeping six feet away from each other.

Although all of us are ultimately responsible for our own behavior, I believe public officials could do a much better job than they are currently doing to motivate the population to keep up the hard work and make the sacrifices needed to slow and eventually stop the virus.

Up to this point, many public health messages have been fear-based, following the template: “X million will become infected and die unless we do Y.”

A National Institutes of Health (NIH) science panel found in 2004 that “Programs that rely on scare tactics to prevent problems are not only ineffective, but may have damaging effects.”

This science panel knew what they were talking about because they could draw upon decades of experience of failed “scare” campaigns to stop smoking, drug addiction and obesity.

It turns out that scare tactics don’t work because people don't want to feel anxious, so they either tune out the messages or rationalize them away by telling themselves things like, “Oh, right, yesterday carbs like whole grains were good for you, now they are supposed to be bad for you: just another example of so-called health experts not really knowing what’s what.”

So if fear tactics won’t work, what will work?

Well, if people adjust their perceptions—consciously or not—so that they can avoid negative emotions, why not replace negative motivational messages with positive ones?

Here’s an example that I think would make people feel more like heroes and less like misbehaving children, and therefore be much more likely to slow the virus than the things we have been hearing recently from governors and public health officials.

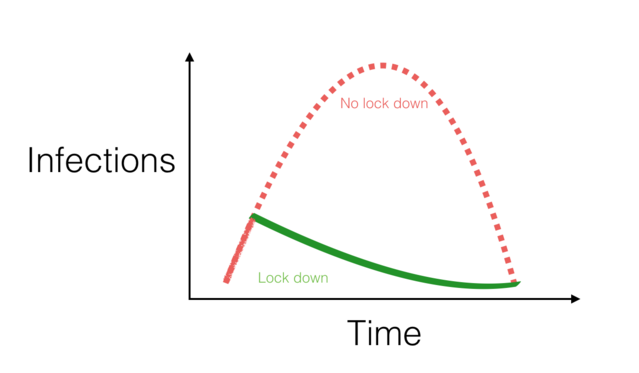

This figure is a simplified graph, abstracted from an upcoming article by D. Ibarra-Vega of the International Research Center for Applied Complexity Sciences, titled "Lockdown, one, two, none, or smart. Modeling containing COVID-19 infection. A conceptual model," in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

The theoretical red curve shows what the number of infections in a population would have been without a lockdown (based on math modeling), while the green depicts the actual number of infections with a lockdown in a given population.

What if, instead of issuing dire warnings about the catastrophes that will befall us if we don’t behave properly, leaders and health officials showed simple curves like these and said, “Look what your sacrifices and exemplary behavior have done to reduce suffering and save lives. Great job public! Thank you!”

I believe people hearing such messages would feel more like heroes than zeros, and as a result, be much more likely to “own” public health and practice safer behaviors as we begin to re-open our society and get our economy—and lives—going again.

Here’s the bottom line: Turning negatives into positives in public health messaging can turn negatives into positives in public health.