Marriage

Single Life in the 21st Century: A Guide to Owning It

Single life is a good life? That no longer counts as a revelation

Posted June 22, 2019

“It was a truth universally acknowledged that by age forty I was supposed to have a certain kind of life, one that, whatever else it involved, included a partner and babies.” But on the eve of her fortieth birthday, Glynnis MacNicol, author of the memoir, No One Tells You This, had no spouse and no children. She felt like a person “being marched to her demise.”

By the end of the book, MacNicol was “quite thrilled” with her life as a single woman with no kids. But it took her forty years before she ever “bothered to seriously question whether I actually wanted to be married with kids.”

Catherine Gray’s father started calling her a spinster when she turned thirty-three. That was devastating. A self-described “raging love-addict,” Gray used to believe, in all seriousness, that “being single means I’m broken, I’m worthless.” By the end of her memoir, The Unexpected Joy of Being Single, Gray still considers herself a romantic. But she has an insight that would have shocked her younger self: “I know I could be satisfied and happy as a forever-single.”

“I didn’t think I would face my fiftieth birthday without a partner, a family,” said Christina Patterson in her memoir, The Art of Not Falling Apart. “I used to think that being single was a kind of affliction, a shameful state that had been handed to me by fate,” she admitted. “It has taken me a very, very long time to realize that I’m probably single because I really like being on my own.”

To all three women, the understanding that single life can be a good life came as a revelation. But it shouldn’t be. Not anymore.

Staying Single for Decades Is Not Surprising – It’s How We Live Now

To be single in the twenty-first century is utterly ordinary. In the U.S., for example, there are nearly as many adults, 18 and older, who are not married as married. Of those unmarried Americans, close to two-thirds have never been married.

MacNicol and Gray were dismayed to be spouseless thirty-somethings. But being single in your thirties is a global phenomenon. Patterson got all the way to fifty and was still single. That’s becoming increasingly commonplace, too. A Pew Research Center report estimates that by the time today’s young adults in the U.S. reach the age of fifty, about one-quarter of them will have been single all their lives.

Single Life Is a Good Life – and It Is Getting Better All the Time

What it means to be single has changed dramatically. Marriage is no longer considered a marker of adult status. It is no longer regarded as essential to a fulfilling life. Fewer women than ever before need a spouse for economic life support. And it has been a good, long time since adults regarded marriage as the permission slip they needed to have sex without shame, to raise children, or to buy a home of their own.

Today, marriage is sold as the royal road to happiness. But that’s not true either. More than a dozen studies have shown that when people marry, they become no happier than they were when they were single, except occasionally for a short-lived blip in bliss around the time of the wedding. MacNicol, Gray, and Patterson described growing trepidation about their single status as the years ticked by. They needn’t have. In a study of thousands of adults between the ages of 40 and 85, those who stayed single became more and more satisfied with their lives as they grew older. People with partners did not experience such a clear upward trajectory.

The same study found that lifelong single people have also been doing better over time, historically. Between 1996 and 2014, single people’s descriptions of their lives grew increasingly positive. Again, for the couples, the results were less straightforward.

We are starting to understand why single life can be so fulfilling. People who stay single, social scientists have shown, typically have more friends and bigger social networks, and they do more to maintain their relationships with friends, relatives, neighbors, and coworkers than people who marry. They are especially likely to be there for people who need sustained help, such as their aging parents. They experience more personal growth, too.

Single women who have never had kids are meant to quiver in fear over the prospect of growing old alone, but they are the ones who have invested in their social circles, so typically, they are not alone. A study of more than 10,000 Australian women in their seventies discovered that the lifelong single women who had no kids were doing better in many ways than all of the other groups of women – the currently married and the previously married, with and without children. The single women were the most optimistic and the least stressed. They volunteered the most and they were the most highly educated. They also had the healthiest body mass index and were the least likely to be smokers or to be diagnosed with a major illness.

What Would It Mean to Own Your Single Life? A Few Approximations

I’m a social psychologist and a lifelong single woman, and I have been researching, writing, teaching, and speaking about single people for more than two decades. As much as I enjoyed the insights and the fine writing in the memoirs I’ve been describing, I have been yearning for something equal to the moment that is single life in the twenty-first century. I wanted to read the memoirs of single women who own their single lives.

Owning single life means going all the way. It is a full, affirming, unapologetic embrace of living single. I don’t want to hear platitudes of grudging acceptance, such as “it’s okay to be single” or “well, it is better than being in a bad relationship.” Spare me the deficit narratives that internalize all that is supposedly wrong with single life. And don’t tell me that you are just marking time until you finish your education or land a great job, and then you will find the perfect partner.

Sasha Cagen gave me some hope when she declared herself a “quirkyalone” in an essay in 2000 and in a 2004 book by that title. The quirkyalone, she explained, “inhabit singledom as our natural resting state…there is no patience for dating just for the sake of not being alone.” They “treat life as one big choose-your-own adventure.”

Single women loved Quirkyalone, the media was intrigued, and the concept enjoyed the pre-Twitter version of going viral. On February 14, 2003, International Quirkyalone Day was declared, and has been celebrated on the same day every year since.

Quirkyalone, though, never fully committed to lifelong singlehood. As hinted in the subtitle of the book, A Manifesto for Uncompromising Romantics, Cagen offered her readers an out. Although a quirkyalone is quirkyalone for life, she said, such a person isn’t necessarily single for life: “…when one quirkyalone finds another, oooh la la. The earth quakes.”

An empowering act for people who are stigmatized is to take a label used to shame them and reclaim it, as happened, for example, with the word queer. In 2015, Kate Bolick reclaimed spinster in the title of her memoir and cultural exploration, Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own. Bolick lauded spinsters for designing their lives mindfully rather than defaulting to the prescribed formula of marriage and children. She profiled five pioneering women from the last century who lived unconventionally, calling them her “awakeners.” Spinster is chock full of affirming and tantalizing insights about spinsterhood then and now. Disappointingly, though, all five of the awakeners ended up marrying, and romantic relationships were featured a little too prominently in the stories of Bolick’s own life for Spinster to qualify as the memoir I had been craving.

Here It Is: The Memoir I’ve Been Waiting for

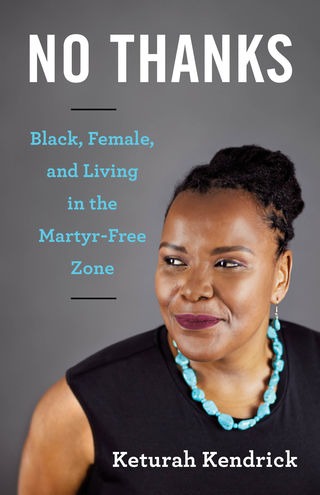

Now, finally, in the year 2019, I have found the writer of my dreams. She is Keturah Kendrick, author of the memoir and cultural critique, No Thanks: Black, Female, and Living in the Martyr-Free Zone. More consistently and compellingly than anyone else I’ve read, Kendrick owns her single life, her choice not to have kids, and every other major decision about how to live her life.

It didn’t take Kendrick four decades to figure out what she wanted. “I’d been clear about who I was ever since the moment the girls in my sixth-grade class, who had been discussing what they would name their future daughters, turned and waited for me to play this bizarre game with them.”

Show me a single woman who can’t quite accept her single life and I can predict where she will point her finger of blame. It is the fault of popular culture, she will say. The marriage plot starts in childhood with the fairy tales. It continues through the teen years and across the entire adult lifespan with novels, movies, TV shows, and love songs all touting romantic love as the answer, and the only true happily ever after. Who can resist?

Keturah Kendrick can resist. The Cosby Show spin-off, A Different World, inspired paroxysms of joy in its fans when Whitley left Byron at the altar to marry her true love, Dwayne Wayne. Kendrick, though, bemoaned what became of Whitley: “The woman who had just last season been entrusted to run someone’s political campaign while still in her twenties was now wringing her hands over failed attempts to make her mother-in-law’s prune cobbler.” Similarly, looking forward to episodes of Ava Duvernay’s Queen Sugar that had not yet aired, Kendrick declares her “hope that Nova will still be allowed to choose herself. Nova has already done the unthinkable: she has turned down a good black man. She has given no reason for doing so other than she did not believe this good black man would support the parts of her that she valued the most.”

How to Respond to Demands that You Justify Your Single Life

You can be the most enlightened woman in the world when it comes to owning your single life and urging others – including even fictional characters – to do the same, but that doesn’t mean that the people around you will nod in agreement. Many will instead insist on swooping in with their pity, their judgment, and their scare stories of what will befall you if you continue along your spouseless, childless path. You know what they are saying: Justify your life. Prove that your time on earth has value. Convince me that you are a contributing member of society.

Comparable demands are not imposed on married people. Marriage is itself a ticket to legitimacy.

One response to the indictment of your dignity is to live in a way that is as unassailable as a single life can be. Glynnis MacNicol did that. She did not have children of her own, but she was there for her single sister when she had her third child, even moving in for a while to care for the other two. She was also there for a friend who had a baby. She helped another friend move from one coast to another. MacNicol also left her own home in New York to live with her mom in Toronto toward the end of her mother’s life, when she had become incapacitated. When MacNicol wasn’t helping others, she was living her own life fully and joyfully. She did great work, spent quality time with her friends, and traveled on her own.

Kendrick opts for more direct responses to the doubts about her life and the digs that single people endure. Here is a sampling:

Don’t you want to be chosen?

“I am not married because I do not want to be. I am not married because I have not seen any iteration of the institution that inspires me to choose it. I am single because I am enough for me. A chance to get chosen neither motivates nor moves me.”

Don’t you want to build a life together?

“I did not fantasize about “building together.” I felt I already built (and quite well, too).”

If you never do have kids, won’t you regret it?

“How can I regret not having something I never wanted?”

You’re selfish.

Kendrick unpacked the selfish slur when a student proclaimed that Oprah was selfish for not having a husband or kids:

“The suffix ish is key. It suggests the word “as” or “like.” …If you are womanish, you are behaving as if you are a woman. If you are mannish, you are acting like an adult male who has a set of expected behaviors and actions dictated by culture and community.

“So what about this ish when added to the root word self? It is my hope that my student examined the word she initially intended as a criticism of Oprah.

“She is selfish.

“She is acting like herself.

“Oh, what a precious privilege.”

Still another possible response to the disapproval of your life choices is to fake it. Pretend, for example, that the idea of having kids is fascinating. Or at least make your lack of interest as palatable as possible. Kendrick tried that, but not for long: “I had stopped making any effort to censor my disinterest in raising children and frame my joy with being childfree in ways that made other people comfortable.”

Over time, the comfort was all Kendrick’s: “The great gift of aging is the ability to release yourself from responsibility for others’ reaction to you. The relinquishing of such burden comes with an additional prize: finding people’s disapproval or shock about who you are ridiculous.”

Owning Your Single Life: Other Ways and Other Times

No one memoir will ever capture all that owning single life can mean. For example, in the memoirs I’ve been discussing, the single women often found their joy in living alone, traveling alone, and sometimes living abroad on their own for significant stretches of time. Not so for Briallen Hopper. In the opening essay from her powerful collection, Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions, she makes an unapologetic “declaration of dependence.” She is single but has no interest in going solo.

To own single life fully, it is not enough to stand up only for yourself. It is also essential to acknowledge and honor all the different kinds of people who matter to you – people other than romantic partners. No one does so better than Hopper. Her deep, nuanced, and unromanticized explorations of friends, roommates, siblings, caregivers, and other members of our “found families” are perfectly attuned to the twenty-first century, when those people, rather than romantic partners, are at the center of so many of our lives.

Owning single life also means recognizing the women who lived unabashedly single lives long before we did. I’ve focused on contemporary single women, but in the 1800s, for example, Louisa May Alcott was already compiling a list of “all the busy, useful, independent spinsters I know,” explaining that “liberty is a better husband than love to many of us.”

Fast forward to the twenty-first century, and now we have women such as Glynnis MacNicol authoring memoirs about single life. MacNicol is a brilliant, sophisticated writer living among the cutting-edge intellectuals and thought leaders of New York City, with opportunities to avail herself of ideas from around the world. And yet, she never once questioned whether she really did want a spouse or children until she was forty years old. Others such as Gray and Patterson believed for far too long that to be single and in your thirties was shameful. That is a failing of our times. It is a victory for the marriage fundamentalists who, for decades, have worked so hard and so systematically to make the case that the ideal way to live was to marry and have children. Their goal was to make that seem so self-evident that hardly anyone would even think to question it.

Keturah Kendrick said “No Thanks” to that agenda. For that, we should all be thankful.

[Want more? I’ve reviewed or discussed all 7 memoirs mentioned in this article, and many other books about single life. Click here.]