Cognition

Invented Languages and the Science of the Mind

Linguists use constructed languages to explore how children perceive language.

Posted October 22, 2019

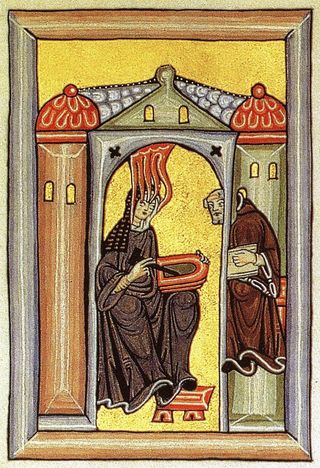

Hildegard von Bingen was something of a medieval genius. She founded and was Abbess of a convent at Rubensberg in Germany, she wrote ethereally beautiful music, she was an amazing artist (one of the first to draw the visual effects of migraines), and she invented her own language.

The language she constructed, Lingua Ignota (Latin for “Unknown Language”) appears to be a secret, mystical language. It was partly built on the grammar of languages Hildegard already knew, but with her usual creativity, she invented over a thousand words, and a script consisting of 23 symbols.

The Lardil, an Aboriginal people of Northern Australia, as well as their day-to-day language, also used a special ritual language, restricted to the adult men. This language, Damin, is the only known language outside of sub-Saharan Africa to incorporate click sounds into its words.

In fact, the sounds of Damin are a creative extension of the sounds of Lardil, showing a deep level of knowledge of how linguistic sounds are made. The Lardil say that Damin was invented in Dreamtime. It certainly shows signs of having been constructed, with careful thought about how it is structured.

While most languages have emerged and changed naturally in human societies, some languages are constructed by human beings. Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota was created for religious purposes and Damin for social and ritual reasons.

More recent constructed languages (or ‘conlangs’), like the Elvish languages J. R. R Tolkien developed for The Lord of the Rings, or the Dothraki and High Valyrian languages David Peterson created for the TV series Game of Thrones, were developed for artistic or commercial reasons. However, constructed languages can also be used in science to understand the nature of natural languages.

There’s a long-standing controversy amongst linguists: are human minds set up to learn language in a particular way, or do we learn languages just because we are highly intelligent creatures? To put it another way, is there something special about language-learning that distinguishes it from other kinds of learning?

Constructed languages have been used to probe this question. There are some striking results which suggest there is indeed something special about language-learning.

One example where constructed languages have been used scientifically is to explore the difference between grammatical words (like the, be, and, of, a) and words that convey the essence of what you’re talking about (like alligator, intelligent, enthral, dance).

This difference is found in language after language. Generally, grammatical words are very short, they tend to be simple syllables, and they are frequent. They signal grammatical ideas, like definiteness and tense. Core meaning words tend to be longer, more complex in their syllable structure, each one is less frequent.

If you look at a list of English words organised by frequency, you have to go down to number 19 before you get to a core meaning word (say), and the next (make) is at 45. The examples of grammatical words I gave above (the, be, and, of, a) are in fact the five most frequent words in English.

One of the properties of grammatical words is that they don’t have fixed positions in a sentence. If you look at the sentence you’ve just read, you can see grammatical words interspersed quite randomly through it. Here it is repeated with those words in bold.

“One of the properties of grammatical words is that they don’t have fixed positions in a sentence.”

Depending on the language, grammatical words appear either randomly, like in this sentence, or they appear fairly consistently either immediately before or immediately after core meaning words, like in this example from Scottish Gaelic.

Cha do bhuail am balach earchdail an cat gu cruaidh

Not past hit the boy handsome the cat hard

which translates as ‘the handsome boy didn’t hit the cat hard’. Here the short grammatical words in bold come immediately before longer core meaning words.

The researchers Iga Nowak, formerly in Glasgow, and Giosuè Baggio in Trondheim, taught different groups of children constructed languages. In some of these languages, the short frequent words had fixed positions, in others, the positions were freer, mimicking what happens in real languages.

Nowak and Baggio reasoned that, if children came with an unconscious expectation about how grammatical words worked, they should find it harder to learn constructed languages where the short frequent words had fixed positions.

Human languages in general don’t work like this, so if children were using a specialised language learning system, they should find such languages difficult to learn.

Nowak and Baggio ran the same experiment with adults. Their idea here was that adults would be able to use other strategies, like counting, and should be good with languages that put short frequent words in particular positions. The children, on the other hand, would have to rely on their innate linguistic sense, if they had any!

The experiments turned out as Nowak and Baggio expected. The children were not capable of learning the artificial languages where the short frequent words appeared in fixed positions, but they were good at learning the other kinds of languages.

The adults, on the other hand, were good at learning the artificial languages that the children were bad at.

Using constructed languages scientifically, Nowak and Baggio have added to evidence that children may come to language learning with unconscious expectations about what the system they are learning should be like. The results are consistent with the idea that a system with grammatical words in fixed positions in sentences is not a natural language, as far as children are concerned.

Human beings love to play with language. Many, over the centuries, have constructed languages to express deep religious, social, artistic and philosophical ideas. Science, too, is a kind of play: we try out different ideas, see how they work out, and learn about the world as we do so. It’s not surprising then that constructed languages have recently become part of the way linguists and psychologists investigate our most human trait, language.

This post was abridged and reblogged from BBC Science Focus.