Coronavirus Disease 2019

Making Sense of Life in the Middle of the Storm

How students' reflections on the impacts of COVID-19 are important to consider.

Posted October 1, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

We are now many months into the disruptions and upheaval that the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced. The events of this year have upended many young adults' lives, disrupting their work and educational opportunities, threatening the health and safety of their loved ones, and depriving them of opportunities to build and maintain close bonds with peers and even romantic partners. This has been a hard, hard time for an entire generation.

Given these major threats, researchers and policymakers have been worried about the short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19. I have been working alongside colleagues across multiple colleges in the U.S. to address ways disruptions to the college experience in spring 2020 initially impacted students and will continue to shape ongoing well-being and functioning for college adults.

I have been working alongside colleagues with expertise in psychological research and the study of life stories, including Robyn Fivush (Emory University; who has provided a concurrent blog post on this topic), Andrea Follmer Greenhoot (University of Kansas), Monisha Pasupathi and Cecilia Wainryb (University of Utah), and Kate McLean (Western Washington University). Together, we have been considering the ways 633 first-year students across our universities reflect on the major disruptions of COVID and how they report on other areas of psychological health.

Our first data collection took place back in April and May 2020, as a vast majority of colleges and universities across the U.S. were closing as a precaution to limit the spread of COVID-19 to students and surrounding communities. These abrupt closings meant very quick departures from campus (or returns from spring break to quickly clear out dorm rooms) and a return home to re-acclimate and adjust to life alongside family, keep up with academic demands and activities (whether broadband access was dependable or not), and to try to address major financial concerns that were pressing for students and families.

This was an incredibly stressful time. Students admit as much as they talked about how they were impacted by COVID-19. Students were frank as they discussed "feeling stuck" at home and isolated from friends; major disruptions to financial security and difficulty filling the gaps due to job search hurdles; ways they were adding more responsibilities to support siblings, parents, and extended family even as they maintained their course activities; and fears for their family's health, especially for immunocompromised or older family. This transition back home was not an extended vacation for students.

As we asked students to provide stories about how their lives had been impacted by COVID-19 disruptions, students nearly always gave richly detailed and elaborative stories—stories that provided clear context and factual content about what was happening at each point in the story, as well as interpretive content about their thoughts, goals, and feelings across different points in the story. These are the kinds of storytelling tools that are fundamental to well-structured stories and stories that are easier to follow. Further, people who tend to use more elaboration in storytelling also tend to report greater psychological health and adjustment. These are individuals who may be better at organizing the experiences of their lives and ultimately finding meaning from their past experiences.

While there are general benefits to the use of elaboration in storytelling, storytelling is a process. How our stories are organized and framed with meaning for our lives changes over time. Researchers like James Pennebaker have shown that confronting challenging life events is not an easy or comfortable task—these attempts lead to negative feelings in the short-term, though those negative feelings can decrease as we purposefully and repeatedly confront challenges from the past.

Similarly, recent collaborative work with colleagues at Emory University and Emory University School of Medicine has shown that the organization of life stories about traumas—here, events that brought people into the emergency department of a local hospital—improves over the following year. That is, elaborative details about traumatic events (i.e., serious car accidents, assaults) increase over the following year, likely as individuals privately rehearse their stories of important events or recount them with others. But these are insights about past events that have reached some form of resolution. Our current work with students is about a major, threatening disruption that was (and still is) ongoing for students. That is, we collected stories of students' experiences "in the midst of the storm" and are hoping to gain insights about how initial storytelling is important, how changes in storytelling look for these students, and how those changes in storytelling are also important for psychological health.

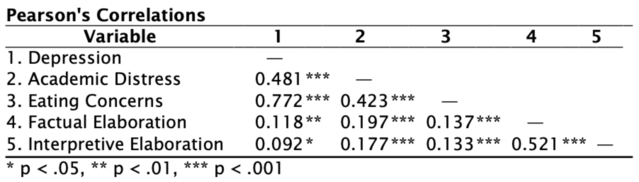

As we've begun to look at the earliest data with students across these colleges, we are seeing some forms of resilience and persistence from students that are encouraging. For example, even with the major disruption in the spring, a vast majority of students across college sites reported being committed to resuming their education in the fall. We also know there are some areas of concern that are not surprising given the stresses of this year. Students who reported on questionnaires about major stress and psychological challenges (i.e., depressive symptoms, academic stress) tended to report higher average scores than previous samples of college adults who were not reporting against the backdrop of COVID-19. This makes good sense. Another finding involving storytelling was that greater elaboration—more detail about facts and thoughts/feelings in reflecting on the impacts of COVID-19—were positively associated with reports of symptoms and stresses.

Students who provided more detail (usually something beneficial for storytelling and understanding the self) also reported more psychological health concerns during this point in the spring. This fits with previous work suggesting confronting challenging events can be distressing at first, and it makes sense that in the midst of some of the most disruptive and painful aspects of this pandemic, many students who are facing those challenges are also recognizing the other stresses and challenges in their lives. All the same, we will be evaluating these trends very closely as we continue to follow student progress over the coming year. The insights from this project will be relevant to psychology and higher education, as we try to identify ways to better respond to student needs.

As this project continues to progress over the coming year, we hope to continue considering the rich information provided in how students make sense of their lives, even in the midst of incredibly painful and challenging circumstances. It is important to understand how students have been impacted by COVID-19—including in ways that go beyond their reports on surveys—and finding the ways meaning-making in the life story helps understand where students are coping and more likely to thrive.

--

This project was supported with funding by the University of Utah Office of Undergraduate Research and University of Utah Seed Fund for Covid-19 Research.

References

Booker, J. A., Fivush, R., Graci, M. E., Heitz, H., Hudak, L. A., Jovanovic, T., Rothbaum, B. O., & Stevens, J. S. (2020). Longitudinal changes in trauma narratives over the first year and associations with coping and mental health. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272, 116–124. https://doi.org/10/ggtqx8

Fivush, R., Booker, J. A., & Graci, M. E. (2017). Ongoing narrative meaning-making within events and across the life span. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 37(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276236617733824

Pennebaker, J. W., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Glaser, R. (1988). Disclosure of traumas and immune function: Health implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.56.2.239

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. https://doi.org/10/dqzwxg