President Donald Trump

Talking About Sexism: Responding to Trump

Triple danger: denial, dismissal, and victim blaming

Posted October 20, 2016

As a therapist and educator, I have come to understand that a core part of what I need to know to do my job properly, and what I feel society needs to know as well, is how to listen and respond to a person who's been abused. What do abuse victims need to know and hear so that healing and care for themselves can be fostered? What do we all need to know so we can help our friends, families, and communities heal from the trauma of abuse?

An Affirmative Approach to Witnessing Abuse

When abuse is witnessed in a way that dismisses as if it's not a big deal, minimizes the victim’s feelings and perceptions about it, denies that the person experienced something traumatic altogether, or transfers blame for the assault onto the victim, something very difficult happens: shame enters. That means a person not only gets hurt by the assault, whether physical or emotional, but the message they receive is that what's happening for them—their reactions, feelings, telling of that story—is grossly inaccurate, being overdramatized, and a result of their own failings. When that happens, a person comes to believe something is wrong with them—a belief that injures the soul and cripples the life project.

When people are silenced because of shame, taught they are responsible for being harmed, and learn that they cannot trust themselves, the emotional duress can literally keep them from advancing in life, on multiple levels. In two decades of working with clients, I have come to learn that this kind of shame-based witnessing is a more difficult problem than the initial assault; it's an injury that cuts deeper and takes longer to heal psychologically.

Donald Trump’s Perpetuation of Abuse and Shame

Let’s look at three examples of how shame is happening now, regarding the Donald Trump tapes and statements.

“This is only locker room talk.”

Why is this language so inappropriate? In my view, to say it's locker room talk as opposed to sexual assault, minimizes and dismisses the power of the assault. It says to the person violated, "Don't make such a big deal of it. This is normal. This happens all the time. It’s not worthy of a big response." That is shaming.

That means to the people given that message—those who were assaulted and the culture at large—"When you have a big reaction, it's not because what happened to you is real and worthy of your reaction; it’s because you’re exaggerating." Shame enters and infiltrates the national psyche, which leads us to a downplaying of all assault. Our nation becomes numb, dismissive, and complicit in not only Trump’s violence but all sexual violence.

"Anyone who has a daughter, mother, or a wife ought to be upset about Donald Trump's statements."

While I’m in full agreement, if I were to make the statement, I would reword it as such: "Anybody who has a wife, daughter, mother, and anybody who has a father, brother, or son…" The addition is needed because otherwise I'm implicitly, indirectly saying, "It's only a woman's issue. It's not a human issue also.” I'm saying to women, "You're a special class, but it's not an issue that all of us have to address, feel, and face." Ghettoizing the issue of sexual assault isolates the subject (in this case, women), making it an issue for a special-interest group, not for us all.

“It's time to get back to the national issues, the important campaign issues, the important presidential issues.”

This statement, again, marginalizes, dismisses the issue of sexual assault, sexual abuse, and sexism in general. Consider the fact that “One out of every six American women has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime,” and “66 percent of victims of sexual assault and rape are age 12-17" (that’s over 60,000 girls each year).

Compare this to the fact that 3,066 Americans were killed in terrorist attacks from 9/11/2001 through 12/31/2014, including the 2,902 killed on September 11, 2001 alone.

The statements and notions above, when they are accepted, or left unchallenged, tell everyone who's experienced some kind of violence, especially women and girls, that the issues they are raising are not that important, are not worthy of their and our response, pain, reaction, of their being taken care of and respected.

In my opinion, perpetuating this kind of shaming message is more dangerous than the initial assault, more dangerous to me than Donald Trump's behavior. The danger is that the national psyche itself is being trained to say, "Maybe it's not a big deal. It's only locker room talk. It's only women's issues. It's not really one of the big national issues.” In short, we can more easily look away and teach our children, families, and communities to live on a level of denial that is nothing less than complicit in the injury to the bodies and psyches of girls, women, boys, and men.

Rewiring the National Psyche: A Restorative Response to Abuse

With Donald Trump’s reaction being an improper and insulting response to abuse, the question is: How do we witness in a way that brings healing, love, and understanding to the people listening? There are three core principles when I listen to someone and teach about shame.

Principle 1: We must indicate that we truly hear what people are saying. Michelle Obama’s recent speech is a perfect example of a non-shaming witness. She said, "This was a powerful individual speaking openly, bragging about sexually assaulting women." She was hearing clearly, not putting a dismissing or minimizing “spin” on Trump’s statement. Her words combated the shame perpetrated by Trump and much of the national dialogue.

Principle 2: We must witness with our words and feelings. When we witness assault, it affects our hearts; it affects our feeling bodies. That means we get angry; we feel hurt. That means we express tenderness, love, confusion, shaking, or fear. When we respond to assaultive acts or words with our feelings, people feel deeply understood, believed, and worthy of our care. This helps prevent shame from entering. Witnessing with logic only, is insufficient.

Principle 3: We must witness by believing people. When a person comes forward and says the have been assaulted, they need to be believed. They can be challenged later on and we can surely examine particular details, but first, from a psychological level, belief has to be poured onto that story; the violation needs to be acknowledged. Believing a person makes them feel protected and sane; it is the first order of business. This crucial step sets the tone for all subsequent healing. Without being believed, shame and self-blame shroud the road to wellness.

It takes immense courage to speak out about injustices done toward us. When we aren’t believed, the courage to continue speaking on our behalf and pursuing justice can be quickly abolished.

What if it takes time for a person to speak out? What if someone can't speak about it for 10 days, 10 weeks, 10 years, two decades? The person then needs to be believed on two levels: not only does the abuse need to be believed but also that it was so traumatic and daunting—that they feel the repercussions of speaking out will be so huge for them—that it really took that long to build the courage and support to finally speak about it. In fact, the EEOC’s task force on sexual harassment, found that the reason people don't speak up about sexual violence is because of the “[f]ear of disbelief and inaction, of not being taken seriously, of being asked what their role was in the behavior." In my words, the fear of beings shamed.

When Anita Hill spoke up about Clarence Thomas’s sexual harassment, people asked, "How come you didn't tell us before?” They tried to invalidate her story, her testimony. They're going to say that to the Cosby victims, the Trump victims. If this goes unchallenged in the national dialogue, it will bring shame to all those who have suffered abuse and developed the courage to speak out over time.

No matter how long it takes before a person decides it’s safe to speak up, we must stop questioning and disputing their delayed action and reaction. Simply put, to speak up about abuse in a culture of shame is an act of power, beauty, and love.

On a personal level, I know it is not always easy to affirm the hurts people accuse me of causing. It is hard to hear that I’ve hurt someone. Nonetheless, no matter how angry the person is, I need to hear, feel, and believe what they’re telling me about how my behavior affected them. Even as a man who is part of a system steeped in sexism, who now feels complicit in the atmosphere, I still must care for the shame I may perpetrate with how I respond.

Donald Trump’s words and behavior have pushed the door open yet further to a national conversation about sexual violence. Let us walk through that door by talking to our children, friends, parents, and communities. Let us become part of the awakening of the great injury that lies nascent in all of us, as we are all either healers or become complicit in the perpetuation of a culture of violence. Let us be models of a culture that brings healing, not shame.

***********************************

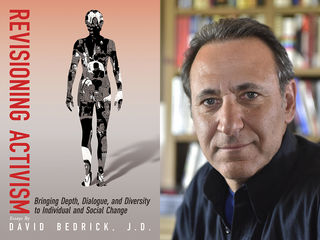

For more information, visit davidbedrick.com.