Self-Esteem

Recalling Competence: A New Technique for Mental Resilience

When dealing with negative emotions, call on your self-efficacy.

Posted March 16, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- There are multiple ways of learning, including classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

- Psychologist Albert Bandura developed social learning theory, which includes that learning can be social, dynamic, and active.

- A mechanism involved in that process is self-efficacy—the belief in your capacity to execute relevant tasks and accomplish your goals.

- Self-efficacy can be a useful tool for emotion regulation. Recalling memories of self-efficacy reduces distress more than memories of happiness, research suggests.

Thought experiment: List 10 things you know how to do. Now, inspect your list. You will surely note that all or most of the things on your list are things you were not born knowing how to do. What you know how to do, you had to learn. We are a learning animal, dependent on learning—rather than instincts—for survival and thriving. No wonder psychologists have long been interested in the processes of learning.

So, how do we learn?

The late 19th-century Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov famously (and accidentally) identified one fundamental learning principle—known as classical conditioning—by which we learn to associate an inert stimulus with the reaction provoked by another, potent stimulus, if the two are repeatedly presented together. Pavlov famously taught dogs to salivate to a tone by pairing it with the presentation of food.

In the early 20th century, the great American psychologist BF Skinner sought to elaborate on Pavlov’s ideas by describing a second learning mechanism, known as operant conditioning, in which learning occurs as a product of the consequences of behavior. In essence, behavior that is rewarded will be repeated and increased, while behavior that is punished or ignored will diminish.

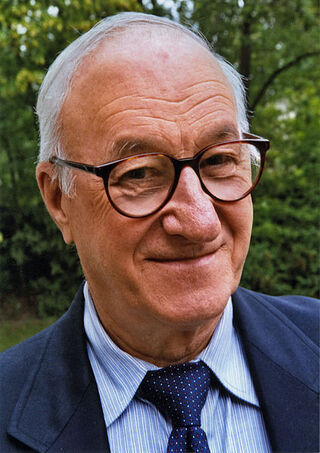

Albert Bandura and the Development of Self-Efficacy

By the latter half of the 20th century, elaborating on Skinner’s ideas, the contemporary psychologist Albert Bandura proposed another important path to learning: social (vicarious) learning, in which we learn by observing, modeling, and mimicking the experiences of others. Bandura demonstrated this type of learning in his famous Bobo Doll experiments from 1961, in which a group of children who watched a model behave aggressively with a Bobo doll proceeded to imitate the model's aggressive behavior when given a chance to play with the same doll later.

By the late 1980s, expanding on his early ideas, Bandura had revised his theorizing to propose the more comprehensive Social Cognitive Theory, which holds that “learning occurs in a social context with a dynamic and reciprocal interaction of the person, environment, and behavior.”

According to Bandura, “people are not just onlooking hosts of internal mechanisms orchestrated by environmental events. They are agents of experiences rather than simply undergoers of experiences.” Therefore, “Thoughts are... emergent brain activities that exert determinative influence.”

In other words, according to Bandura, we act on our environment, and our beliefs shape our actions. The central mechanism of our agency is what Bandura called “perceived self-efficacy,” defined as “belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations.” In other words, self-efficacy consists of your beliefs about your competence to perform certain tasks and skills and to meet certain challenges ahead. These beliefs play a major role in deciding which behaviors you choose to engage and persist in and how well you’ll manage obstacles and challenges along the way.

According to Bandura, efficacy beliefs are acquired and shaped through several sources. These include mastery experiences, as when we overcome challenges and obstacles; vicarious experiences such as witnessing social models who are similar to us persevere and succeed; social persuasion, when others encourage and persuade us that we are capable; and managing our physiology by enhancing our physical status, reducing stress, and correcting misinterpretations of bodily states, as when we learn to regard physiological arousal not as motivating energy rather than scary malfunction.

Efficacy beliefs, in turn, regulate behavior via four processes: cognitive—when your beliefs affect your behavior; affective—when you manage your emotions in ways that let you exert control over stressors; behavioral—when your effective behaviors turn dangerous into safe environments; and by exercising choice—such as when you select which environments and activities to get into in the first place.

The concept of self-efficacy has, by and large, failed to enter the cultural conversation beyond academia, receiving limited play in the popular media. It has never enjoyed the cultural cache and name recognition of, say, “self-esteem,” "positive thinking," or, more recently, “self-care.” Lay readers of this column may have never heard of it.

This is unfortunate, because research has shown that self-efficacy is indeed a causal factor in shaping, explaining, and predicting a host of behavioral and mental health outcomes. For example, self-efficacy has been found in several meta-analyses to predict health-related outcomes, as well as work and academic performance.

To Combat Negativity, Choose Self-Efficacy Over Happiness

Self-efficacy, then, is a potent individual resource, but can we summon the power of self-efficacy at will to improve our coping during times of emotional upheaval? An intriguing (albeit small) new study (2021) by University of Zurich psychologist Christina Paersch and colleagues suggests that this may indeed be possible.

The authors define self-efficacy as: "the belief that we have the ability to influence things to at least a small degree, even if some things are unchangeable." Their study included 50 healthy participants who were asked to identify a personal negative emotional memory. Participants were then divided into two groups prior to reappraising the memory. Participants in one group were instructed to recall a positive event from their lives (e.g., a beautiful nature walk) while those in the other group were instructed to “think of a time in which they felt they were particularly self-efficacious” (e.g., passing a difficult exam).

Results showed that recalling the self-efficacy experience “was associated with significant reductions in distress, and subjective physiological responses” upon reappraisal of the negative emotional memory. "Recalling a specific instance of one's own self-efficacy proved to have a far greater impact than recalling a positive event," the researchers assert. Recalling one’s self-efficacious past behavior appeared to have helped participants reevaluate the negative experience from a different perspective, resulting in a new, less negative appraisal.

"Our study shows that recalling self-efficacious autobiographical events can be used as a tool both in everyday life and in clinical settings to boost personal resilience," the researchers argue. “These findings suggest that recalling self-efficacy episodes may promote adaptive self-appraisals for negative memories, which in turn may contribute to recovery from stressful events and, with further research, may prove to be a useful adjunctive strategy for treatments such as CBT.”

More research is needed, but the take-home message from this preliminary work is that to deal well with emotional upheaval, it may prove better to recall our past competence than our past happiness.

LinkedIn image: Studio Romantic/Shutterstock