Intelligence

How Eye Gaze Biases Our Perception of Head Orientation

New research shows that Wollaston's gaze illusion also works in reverse.

Posted November 28, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Wollaston's gaze illusion (1824) demonstrates that perceived gaze direction is influenced by head orientation.

- New research examined whether this effect also works in reverse.

- The researchers confirmed that judgments of head orientation are systematically influenced by the perceived direction of gaze.

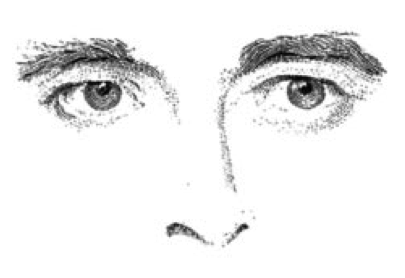

Wollaston's gaze illusion (1824) is one of the most powerful demonstrations that we process faces holistically, rather than feature by feature. In the demo that I often present in my seminar on Illusions, I first ask students to point toward the direction where the eyes of this image are looking:

Inevitably, the students point to the right.

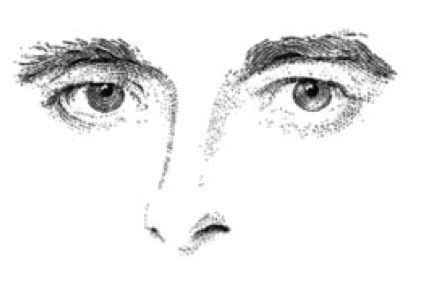

I then present students with the following image, and ask them to point toward the direction these eyes are looking:

Without a second thought, students point directly at themselves, indicating that the eyes appear to be looking directly at them.

Finally, I reveal that in fact the two sets of eyes are actually identical:

The lesson behind this demonstration is that we don't judge a face by one of its features or a subset of its features, but by the combined appearance of all of its features. Although the eyes alone might suggest a particular emotional expression, or in this case a particular direction of gaze, when the rest of the face and head are visible, the true emotion or gaze direction can be seen.

Although the Wollaston illusion has always been described as unidirectional (i.e., the head orientation affects the perceived eye gaze; not the other way around), new research suggests this illusion actually works both ways.

An inversion of the Wollaston illusion

In a new paper published in the journal i-Perception, researchers Heiko Hecht, Ariane Wilhelm, and Christoph von Castell presented observers with Wollaston's original drawings as well as a computer-generated 3D avatar face to study the two-way interaction between gaze direction and head orientation. In one block of trials, observers were asked to judge the gaze direction of the face—i.e., which way the eyes are looking—by indicating where the face's gaze would intersect a horizontal bar that was placed in front of the monitor. In the other block, participants were asked to judge the orientation of the head—i.e., where the head direction would intersect the horizontal bar.

The first set of results were based on Wollaston's original drawings. The authors found that (1) the position and orientation of the nose biased judgments of gaze direction by about 7 degrees, but it biased judgments of head orientation by an even larger amount—about 19 degrees on average. The authors argue that this asymmetry makes sense, as the nose is firmly attached to the head and thus can function as a reliable cue to head orientation.

The next set of results were based on a computer-rendered 3D avatar in which the orientation of the head and eyes could be manipulated independently. The authors found that the head orientation of the avatar actually repelled the perceived gaze direction; that is, judgments of gaze direction were systematically biased away from the orientation of the avatar's head, a reversal of Wollaston's effect. In contrast, the authors observed an attracting effect of the gaze direction on the perceived head orientation. That is, judgments of head orientations were systematically biased toward the direction of the avatar's eyes.

Hecht and colleagues argue that the disparate findings based on Wollaston's drawings and on the 3D avatars were likely due to the salience of the irises in the avatars. Further, they suggest that the reason gaze direction can affect perceived head orientation is due to the importance of gaze perception in day-to-day life.

As social creatures, humans are fundamentally interested in understanding others' gaze direction. The perceived orientation of the nose, the head, and the other facial features serve as cues to refine the estimation of gaze. Because of the primacy of gaze direction, other judgments (in particular, head orientation) are seen as secondary, and subject to be influenced by the perceived gaze direction.

A main takeaway from this study is that the way we perceive local features in a face (e.g., the eyes) is influenced by the appearance of more global facial features that indicate the direction of the head. And conversely, the way we perceive global facial features is similarly influenced by the appearance of the eyes. Thus, holistic processing in faces works in both directions: global features influence local processing, and in turn, local features influence global processing.

References

Wollaston, W. H. (1824). On the apparent direction of eyes in a portrait. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 114, 247–256.

Hecht, H., Wilhelm, A., & von Castell, C. (2021). Inverting the Wollaston Illusion: Gaze Direction Attracts Perceived Head Orientation. i-Perception, 12(5), 20416695211046975.