Pregnancy

Ectopic Embryos: Pregnancy in the Wrong Place

Peculiar cases of embryos developing outside the womb

Posted April 18, 2019

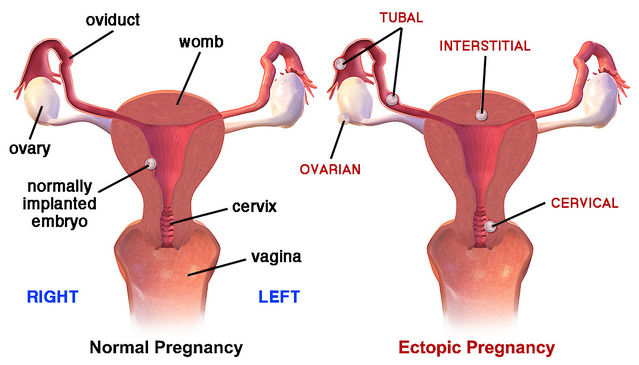

A young woman, glad to be pregnant and eager for motherhood, was seemingly doing fine for several weeks. As menstruation had stopped, she was worried when she experienced blood loss from her vagina and pain in her lower belly. Her physician immediately arranged an ultrasound examination, and operation quickly followed: The embryo was developing in the wrong place, in one of the egg-carrying tubes (oviducts) instead of the womb itself. This life-threatening condition requires surgery to remove the misplaced embryo.

Development of an embryo in the wrong place — ectopic pregnancy — affects one or two of every hundred pregnancies and is a significant cause of fetal and maternal death even in countries with good health services. 99% of ectopic pregnancies occur when a fertilized egg implants in an oviduct instead of descending all the way to the womb. In very rare cases, just once in every 5,000 to 10,000 pregnancies, the fertilized egg does not enter the oviduct at all and implants in the belly cavity (abdominal pregnancy). There, the embryo may attach to the ovary, the outside of the womb or the intestine. As for many other aspects of women’s reproductive health, the incidence of ectopic pregnancy increases steeply as age increases above 25.

Problems with blocked oviducts

Ectopic pregnancy is often caused by blockage of some kind in the oviduct. In fact, the impetus to address this topic came from a striking finding reported in my previous blog piece The Sperm that Fertilizes: Champion Swimmer or Lucky Winner? (posted March 28, 2019). A 1994 paper by Amir Ansari and Eric Miller reported ectopic pregnancy in a woman whose left oviduct had no connection with her womb. During surgery for a previous ectopic pregnancy, part of that oviduct near the womb had been cut away. A second ectopic pregnancy was detected less than six months later. An egg released by the left ovary had evidently been fertilized by sperms that migrated up her right oviduct and then across her belly cavity. Because the left oviduct was no longer connected to the womb, the fertilized egg could not travel down to the womb to attach in the normal way, and an ectopic pregnancy was the outcome.

It is easy to identify the side on which egg release (ovulation) has occurred. Like all other female mammals, women have two ovaries, one on each side of the body, where eggs develop in individual balls of cells (follicles). Women typically release only one egg per cycle, apparently at random from either the left or the right ovary. After egg release, the empty follicle is converted into a yellow body (corpus luteum). So the side where ovulation occurred can be simply recognized by finding out which ovary contains a yellow body.

Surprisingly, several medical reviews of ectopic pregnancies have revealed that ovulation occurred on the opposite side of the body in more than a quarter. In those cases, the egg must have migrated across the belly cavity after release, entering the oviduct on the other side.

In papers published in 1962 and 1963, Leslie Iffy proposed an intriguing, but little-cited, possible explanation for ectopic pregnancy. Backdating from births indicated that conceptions had actually taken place in the previous cycle before the last observed menstruation (the standard reference point for dating pregnancies). In other words, those conceptions occurred too late to prevent menstruation. According to Iffy’s “Reflux Theory”, the mechanical effect of the menstrual flow prevents the developing embryo from descending to the womb in the normal way, so it implants in the oviduct instead. But Iffy’s interpretation has not been tested with follow-up studies.

Sperms swimming across the abdomen

So both eggs and sperms can migrate across the abdomen. Evidence for eggs crossing the abdomen is straightforward as the ectopic pregnancy and the ovary that released the egg are located on opposite sides of the body. However, if the sperm that fertilizes the egg migrates across the abdomen — as in the case reported by Ansari and Miller in 1994 — the developing embryo will be on the same side as the ovary that released the egg, as in normal pregnancy. Additional examination is needed to find out whether the oviduct is blocked somewhere between the site of embryo implantation and the womb.

Because conditions associated with an ectopic pregnancy may not be fully explored at the time of surgery, cases in which sperms crossed the abdominal cavity before fertilization are not well documented. Ansari and Miller did cite one earlier paper, published in 1979 by Karel Metz and Luigi Mastroianni, reporting a tubal pregnancy following the migration of sperms across the abdomen. Other reports have appeared sporadically. Quite recently, Francesca Monacci and colleagues reported a five-week ectopic pregnancy in an 18-year-old woman. Implantation of the embryo had occurred in the upper end of an oviduct that was not connected to the womb because of a developmental abnormality. In this case, too, the fertilizing sperm must have migrated across the abdominal cavity.

In 2004, Gerard Nahum and colleagues published a general overview of almost three hundred ectopic pregnancies in women with oviduct blockage on one side. They estimated the likelihood of migration of sperms across the abdominal cavity and concluded that there is a 50:50 chance of an ectopic pregnancy occurring. So such migration of sperms seems to be common, and normal pregnancies may often result in this way if there is no oviduct blockage. Challenging accepted wisdom, Nahum and colleagues suggested that many fertilizations may occur in the abdomen rather than in the upper end of an oviduct. It certainly seems unwise to leave an incomplete upper oviduct in place after surgery, and a take-home lesson is that particular care is needed to ensure that tying of the oviducts for sterilization is completely reliable.

DES daughters and ectopic pregnancy

In addition to oviduct blockage and eggs or sperms migrating across the abdomen, other factors can also be involved in ectopic pregnancy. For instance, abnormal development of a woman’s reproductive tract can also contribute. One notorious illustration is provided by the treatment of pregnant women with the synthetic compound DES (diethylstilbestrol), which was inadvisably used as a cheap substitute for natural estrogen. Once the health dangers were clearly realized in 1971, DES was withdrawn from general use in the USA. But by that stage, millions of pregnant women in the USA and Europe had been exposed to DES. Nancy Langston expertly recounts the tragic story in her 2010 book Toxic Bodies.

DES had direct adverse effects on women who took the drug. However, particularly alarming side-effects eventually emerged from studies of women whose mothers were treated with DES during pregnancy. In other words, effects were transmitted from one generation to the next, and many studies have now been conducted on deleterious health outcomes in “DES daughters”. A 2011 paper by Robert Hoover and multiple colleagues is particularly informative. These authors analyzed long-term follow-up data for almost 4653 women exposed to DES in the womb, comparing them with 1927 unexposed controls. Lifetime risks up to age 55 were found to be strikingly increased for many reproductive disorders: infertility, pre-eclampsia, miscarriage, pregnancy loss, stillbirth, premature birth, early infant death, ectopic pregnancy, early menopause, breast cancer, and cervical cancer. The result for ectopic pregnancy was particularly pronounced, with an almost fourfold greater risk compared to women who had not been exposed to DES in the womb.

Sex cells that stray

On the one hand, an ectopic pregnancy is testimony to the dogged persistence of human sex cells, which somehow manage to meet for fertilization even under challenging circumstances. On the other hand, this adverse outcome directly threatens the survival of mother and fetus and requires rapid intervention. The young woman mentioned at the beginning was fortunate in that her condition was quickly recognized and followed by prompt surgery. It is important to know about this unusual complication and to seek medical advice if bleeding or lower abdominal pain arise during pregnancy.

References

Andersen, A.M.N., Wohlfahrt, J., Christens, P., Olsen, J. & Melbye, M. (2000) Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. British Medical Journal 320:1708-1712.

Ansari, A.H. & Miller, E.S. (1994) Sperm transmigration as a cause of ectopic pregnancy. Archives of Andrology 32:1-4.

Berlind, M. (1960) The contralateral corpus luteum: an important factor in ectopic pregnancies. Obstetrics & Gynaecology 16:51-52.

Blausen Medical, Scientific and Medical Animation (2015): Ectopic Pregnancy, video.https://blausen.com/en/video/ectopic-pregnancy/

Hoover, R.N., Hyer, M., Pfeiffer, R.M., Adam, E., Bond, B., Cheville, A.L., Colton,T., Hartge, P., Hatch, E.E., Herbst, A.L., Karlan, B.Y., Kaufmann, R., Noller, K.L., Palmer, J.R., Robboy, S.J., Saal, R.C., Strohsnitter, W., Titus-Ernstoff, L. & Troisi, R. (2011) Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. New England Journal of Medicine 365:1304-1314.

Iffy, L. (1962) Contribution to the pathological mechanism of ovarian, endometrial and cervical pregnancies. Gynaecologia 153:188-204.

Iffy, L. (1963) The role of premenstrual, post-mid-cycle conception in the aetiology of ectopic gestation. An evaluation of the reflux theory. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire 70:996-1000.

Iffy, L. (1963) Embryonic studies of time of conception in ectopic pregnancy and first trimester abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology 26:490-498.

Langston, N. (2010) Toxic Bodies: Hormone Disruptors and the Legacy of DES. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Metz, K.G. & Mastroianni, L. (1979) Tubal pregnancy subsequent to transperitoneal migration of spermatozoa. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 34:554-560.

Monacci, F., Lanfredini, N., Zandri, S., Strigini, F., Luchi, C., Giannini, A. & Simoncin, T. (2019) Diagnosis and laparoscopic management of a 5-week ectopic pregnancy in a rudimentary uterine horn: A case report. Case Reports in Women's Health 21,e00088:1-3.

Nahum, G.G., Stanislaw, H. & McMahon, C. (2004) Preventing ectopic pregnancies: how often does transperitoneal transmigration of sperm occur in effecting human pregnancy? British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology (BJOG) 111:706-714.