Happiness

Systems Thinking and How Pursuing Happiness Backfires

What can flows and feedback teach us about chasing happiness?

Posted January 21, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Several lines of research find that pursuing happiness too intensely can actually lead to less happiness.

- Those who value happiness the most rate themselves as less satisfied with their lives and more depressed.

- Researchers suggest that feedback processes from expectating a lot of happiness can lead to negative feelings.

- Identifying effective emotion regulation strategies, and letting go of expectations, may help.

We all want to be happy. At least that seems to be the message that we get from society: Pursue happiness, because happiness is the ultimate goal. In a previous post, I described how a leading psychotherapist sees many of the messages we get about what to want as linked to happiness. If we make enough money, we’ll be happy. If we get famous enough, we’ll be happy. If we are attractive enough, we’ll be happy. Yet emerging scientific research on emotion shows how the pursuit of happiness itself can cause problems–and it often backfires. To understand why, we need to delve into systems thinking.

In their article “The Paradox of Pursuing Happiness,” emotion researchers Felicia Zerwas and Brett Ford try to explain a counter-intuitive set of research findings: The more people want to feel happy, the less happy they tend to be. Here are some examples:

- People who have just been told about the benefits of happiness, and who should therefore value it more, actually report feeling less positive emotion after watching a positive movie clip.

- People who have just been told about the benefits of happiness report feeling more lonely after watching a movie clip showing a positive experience of connection.

- People who report valuing happiness more also report having less satisfaction with their lives and lower overall psychological well-being.

- People who value happiness a lot tend to have more depressive symptoms, both as reported by themselves and as rated by clinicians.

In short, pursuing happiness too intensely seems to make it harder to find.

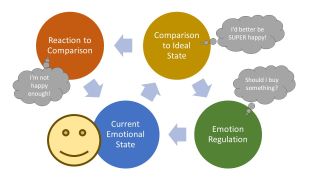

Zerwas and Ford explain this by considering a person’s state as part of a dynamic model. (They use the term “cybernetic model,” referring to a branch of systems science that deals with feedback loops.) The model works like this:

- You have an emotion goal; in this case, a level of happiness you want to achieve.

- You compare your goal to how you’re feeling.

- If you’re not meeting your goal–i.e., you’re not happy enough–then you try to change it via some kind of emotion regulation (e.g., watch an episode of your favorite sitcom).

- Your comparison also leads to an emotional reaction, i.e., if you’re not as happy as you wanted, you feel negative. (They call this a meta-emotion.)

- Both your emotional reaction to the comparison, and the actions you take to regulate your emotions can change your feelings, i.e., make you more or less happy.

This model can lead to a few problems. Perhaps the most obvious one–the one that might have first leaped to mind as you read this–was that the emotional reaction to your happiness level could lead you to feel negative about positive experiences that just aren’t positive enough. In other words, if you set your emotion goal to “sublime happiness,” then even when you’re just having a low-key, pleasant experience, you will end up disappointed. That disappointment itself actually takes away from the happiness you would have experienced without so many expectations.

The second issue that comes up in Zerwas and Ford’s review of the research is that people often aren’t great at picking out emotion regulation strategies that really will make them happy. For example, people often think spending money on themselves will make them happy, but research finds that spending money on other people often leaves us feeling happier. There is a broader literature on which emotion regulation strategies reliably do lead people to feel happier, but the short version is that we often aren’t great at predicting what will make us happy.

Setting the emotion goal itself also causes problems. You can set your goal for happiness too high, as we just reviewed, but you can also set happiness as a goal in an inappropriate way. For example, you might need to have a difficult conversation with a friend or colleague where you work through a disagreement. Done right, that conversation will probably not lead to an experience of happiness. But if you continue to prioritize feeling happiness even during that exchange, you will likely find it extra negative. For example, research finds, unsurprisingly, that people who want to feel happiness during a confrontational situation actually end up feeling less happy.

So what do we do? The authors suggest that embracing principles of mindfulness may be one way out of this paradox. Mindfulness practices emphasize watching, without judging, what is happening in the present moment. Cultivating this kind of equanimity about one’s feelings is a direct counter to the negative emotional reactions that can occur when a happiness goal isn’t met.

Another possible solution is learning more about emotion regulation strategies. This can include reading research on what scientists have found leads people to report more happiness, but it should also involve some personal trial-and-error. You might find that, after a stressful experience, a nap is particularly helpful for clearing your head and returning to a positive state. Or you might find that naps leave you groggy and in a lower mood for several hours afterward. Identifying strategies and noting what does and doesn’t work can help you find more positive emotional states–without needing to focus on whether you’re meeting your goals.

Finally, my own advice based on my broader current reading would be to consider the messages that you’re consuming from society. Does that TikTok channel make it seem like having a snatched waist will be the thing that finally makes you happy? Does that YouTube channel giving financial advice make it seem like getting rich quick will finally get you to a positive headspace? We’re awash in social messages, and these can often lead you into exactly the traps Zerwas and Ford describe: pushing you to set unrealistic goals for yourself, and identifying emotion regulation strategies (e.g., buying beauty products) that aren’t actually effective. Consider instead the system you find yourself in, and how happiness really flows into your life.

References

Zerwas, F. & Ford, B. Q. (2021). The paradox of pursuing happiness. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 39, 106-112.