Extroversion

When to Take Statistics Personally

The promise of person-centered statistical modeling

Posted April 22, 2019

Don’t take statistics personally. They don’t take you personally. At least, most of them don’t.

The typical statistics that most social scientists (and curious non-scientists) encounter is only one of two types. Although many people working with statistics every day might never encounter it, there is a whole other way of conceptualizing data that has big implications.

I was taught statistics for psychology using conventional examples: data collected from many people measured at one time point.

For example, I might be interested in testing whether being extraverted is related to feeling lonely. I would ask many people to fill out a questionnaire on how extraverted they are and how lonely they feel, and then calculate a correlation between these variables. (New evidence combining results from many studies suggests that these two variables have a reasonably large negative correlation, r = -.37. People who are more extraverted report being less lonely).

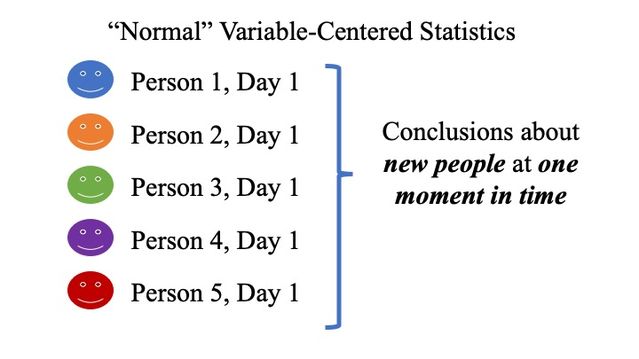

This statistical result is what’s called a “variable-centered” analysis (or nomothetic in the technical literature). It implicitly assumes that there is one underlying relationship between these two variables for all people. If you want to know how lonely someone is, figuring out how extraverted they are will help you answer the question.

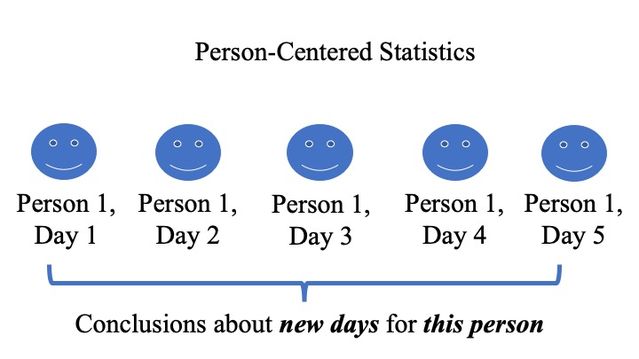

The other way to look at the question would be to examine one person at many time points. Let’s say you asked someone to fill out a questionnaire every day for a year, reporting how extraverted and they felt.

You could then analyze how extraversion is associated with loneliness for this specific person.

You might find the same association: on days when this person is more extraverted, they feel less lonely. Maybe feeling more extraverted means they are more likely to reach out to friends and socialize, and that makes them feel less lonely.

But you could find a different association. Maybe this person doesn’t have friends who are available very often, and on days when the person is more extraverted, they can’t find someone to hang out with. They ultimately end up feeling lonelier on these days. For this person, extraversion is positively associated with loneliness.

This is a person-centered analysis (called idiographic in the technical literature). This analysis assumes that there can be a different underlying relationship between variables for each person. If you want to know how lonely someone is, you need to know how extraverted that person is on that day—but you also need to know what the specific association between the variables is for that person.

So which analysis is right?

Both, but they answer different questions. The variable-centered analysis takes what I’d call the Public Policy Perspective.

Let’s say I was trying to set up a rule to help therapists figure out whether their clients were lonely. I would use the variable-centered analysis to help here, and I would recommend that therapists ask introverts (e.g. people low on the extraversion scale) follow-up questions to see if they were feeling lonely.

Notice how the type of data I’m using matches the type of decision being made: I collected data on a lot of people one time, and I’m making a recommendation about what a lot of people (e.g. many therapists) should do at one time (e.g. a single screening interview).

This is typically the way public policy is set. A governing body decides on a set of guidelines that will be helpful, on average, to people in general and applies it widely.

The person-centered analysis takes what I’d call the Personal Trainer Perspective.

Let’s say I was a therapist treating someone frequently felt lonely. I would use a person-centered analysis of this specific client to help here, first determining how extraversion is related to loneliness.

If this person felt more lonely on days when they were introverted, I would try to figure out strategies that could help them address their loneliness on introverted days. Maybe we would discuss ways to be around people even when they were low energy, like going to a coffee shop.

But if the person felt more lonely on days when they were extraverted, I would try to figure out strategies that could help them address feeling like they didn’t have friends around to connect with. Maybe we would discuss ways to reach out to new potential friends who had greater availability or to schedule social engagements for days and times when they tended to feel extraverted.

Again, the decision I’m making matches the type of data I collected. I would use many observations of the single person to make a recommendation that works only for that individual. Like a personal trainer, I’d be concerned with coming up with the best training plan for this one person. It could use recommendations common to others, but the plan only needs to work for one person.

The person-centered approach is fundamentally about the way that people collect and make sense of data, and so has many potential applications. We could develop personalized therapies, but we could also develop personalized medical treatment plans, personalized educational plans, or personalized positive psychology interventions that help a person find more meaning and happiness in their life.

Ultimately, researchers who have worked for a long time in this area have begun thinking about ways of combining these levels of analysis. For example, Katie Gates (a quantitative psychologist who trained with an early “person-centered pioneer” Peter Molenaar) has developed an algorithm that can identify differences in the way people’s brains process information. She has used this to identify links between brain regions common to all people, common to smaller subgroups of people, and unique to specific individuals.

Most data in psychology and medicine is only collected and analyzed from the Public Policy Perspective. This data tells us about what happens with people “in general”, but it doesn’t tell us what will work for one specific person over time. Don’t take this data personally if it doesn’t provide a recommendation that works for you.

Instead, remember that only personal data—observing how you change over time—can make truly personal statistical predictions.