Decision-Making

Betting on Low-Probability Outcomes

Sometimes low-probability outcomes pose disproportionate consequences.

Posted July 21, 2020

Betting typically involves knowledge of probabilities, and we often think about it in the context of activities like poker games, slot machines, or playing the lottery. Yet every decision we make involves a bet of some kind. If we choose to order a pizza from our favorite establishment, we’re betting that (1) the costs we incur (such as the price, time spent waiting for the food to arrive) will (2) lead to an outcome (pizza arrives), from which (3) we will derive some benefit (like enjoying the pizza, no longer being hungry) that (4) we assess as worth the costs. For decisions like this and many others we make daily, we’re betting on what we believe to be an extremely high-probability outcome.

Many people learn that the key to good decision making is the mastery of probabilities. In fact, a lot of contemporary decision-making experts will gladly tell us that betting on a high-probability outcome is more logical than betting on a low-probability outcome (see Figure 1)[1]. Sometimes, though, it makes sense to hedge our bets and make decisions as if we’re betting on a low-probability outcome. This is the central premise behind error management theory.

Error Management Theory

Error management theory (EMT) was described by David Buss and Martie Haselton to explain what are often described as decision-making errors—errors in which our decision contradicts what we would expect if only considering the probability of a given outcome. Buss and Haselton claimed that human decision making evolved in such a way that it sometimes makes sense to hedge our bets. That is, sometimes a low-probability outcome poses significantly greater potential payoffs than a higher-probability outcome. Thus, it may be rational to make a decision as if betting the low-probability outcome will occur.

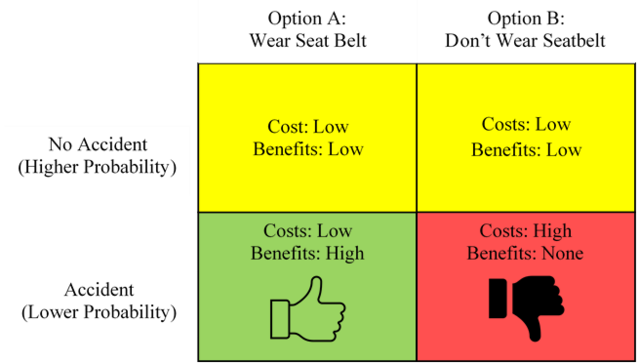

Although this may sound counterintuitive, consider the following scenario. According to an esurance infographic, there is a 1 in 366 chance of being in a car accident on a 1,000-mile trip (a 0.3% chance). Is it logical to wear our seat belt, given the low probability of getting into a car accident? The answer is likely yes because, according to the CDC, in the unlikely event we get into an accident, there is around a 50% greater chance of survival if wearing a seat belt. Therefore, we have two options. Option 1 assumes the high-probability outcome will occur (that we will arrive safely), and thus, there is no added benefit of wearing a seat belt. Option 2 recognizes the low-probability outcome could feasibly occur (that we get into an accident), and therefore it makes sense to wear a seat belt (Figure 2).

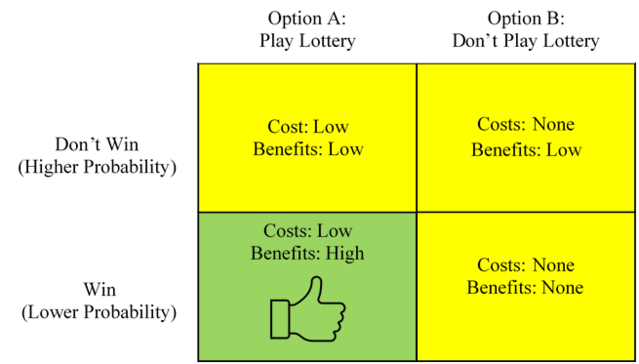

We can also apply EMT to situations where the low-probability outcome poses drastically more positive consequences. Lotteries are a primary example of these types of situations. From a probability standpoint, winning any lottery necessarily represents a low-probability outcome (Figure 3). Yet, many people choose to play them. A big reason for this is that they perceive the consequences of winning as drastically more impactful on them than the consequences of losing. Therefore, lottery players choose to make their decision—accepting the cost of a $10 lottery ticket—as if they’re betting the low-probability outcome will occur (e.g., hoping to benefit by winning the jackpot)[2].

Not everyone, though, will respond the same to differences in consequences between low- and high-probability outcomes. There are some important (and subjective) factors that influence the degree to which high-impact, low-probability outcomes affect our decision making.

What This Means for Decision Making

In my previous post, I talked about the importance of tradeoffs when considering costs, benefits, and probabilities. Trade-offs are just as important when discussing how EMT applies (or doesn’t) to various decisions we make. To effectively apply EMT means that we have decided that:

- The low-probability outcome poses salient consequences that would be greatly more impactful than those posed by the high-probability outcome[3];

- The low-probability outcome is likely enough[4] to occur that it is worth betting on[5];

- We anticipate some potential benefit from betting on the low-probability outcome;

- We decide the costs of betting on the low-probability outcome are worth the potential benefits[6].

There are a lot of pitfalls in this process, especially since many decisions like this occur unconsciously. Errors we make are often the result of failing to consider all four of the elements listed above; over- or underestimating costs, benefits, or probabilities; failing to recognize some important costs or benefits, or making faulty assumptions that adversely affect the decision-making process (e.g., seeing a connection between costs and benefits that does not actually exist[7]).

We can extend this out to better understand why there is so much variability in people’s decision making regarding COVID-19. Getting COVID is a low-probability event, and people will vary in how they apply the fundamentals of EMT. For example, they will vary in:

- Their assessment of the salient consequences if they get COVID (ranging from no symptoms to possible death),

- Whether the probability of getting COVID is high enough that they need to take steps to reduce that probability,

- Whether some costs (e.g., social distancing, wearing a mask, limiting time spent in large groups) would offer the benefit of a reduced probability of getting COVID, and

- Which costs are worth that benefit.

When we consider the degree to which people may differ in these assessments, is it any wonder we see such variability in their behavior?

References

[1] Many of these recommendations assume the costs of various options are roughly equivalent.

[2] Though EMT applies to both positive and negative low-probability outcomes, there are cases in which low-probability negative outcomes are likely to produce more universal application of EMT (as evidenced by the fact more people wear their seat belt than play the lottery).

[3] The decision of which outcome more impactful is often a function of the value we place on specific costs and benefits.

[4] What it means for a low-probability outcome to be likely enough to occur will vary based on how impactful its consequences are if it does. Consequences that pose more impact may necessitate a lower probability threshold than less impactful consequences.

[5] For example, many people would be more likely to place a $20 bet where they have a 70% chance of winning, but they’d be less likely to choose to have an elective surgery if they only have a 70% chance of survival.

[6] There is a threshold above which most people will appraise the costs of betting on the low-probability outcome as exceeding the anticipated benefits; they will be generally unwilling to exceed those costs.

[7] Such as when people believe that choosing to opt out of vaccines will decrease the likelihood their child will develop autism or when people believe some new age therapy will benefit them when it won’t.