Last week Dave Fanning was kind enough to invite me on his radio show to talk about a few of my favorite things—sex and violence. He wanted to ask what, if anything, psychologists had to say about why humans are so interested in true crime shows like Making a Murderer, and was there anything wrong with this?

My answer to this was pretty conventional—it’s not a new thing, we’ve been interested in these sorts of themes for a long time, and as long as someone isn’t taking an unhealthy interest in copying those actions then it seems safe enough. There are so-called hybristophiles (literally: “those who love arrogance”) who seem to have a very unhealthy interest in murderers…but that’s a post for another time.

Pretty much as long as we’ve been keeping records, those records have been ones that involve love and death. And why wouldn’t they—these are the events that mark the beginning and end of life. The only thing left over is taxes…

Actually—taxes are pretty recent. Humans have led most of their lives without them. But they haven’t been able to live their lives without being painfully aware of who is to be trusted and who not, who is dangerous, who might want to have babies with you, and so on. Anthropologists tell us that the fireside stories of our hunter-gatherer neighbors—one of our key bits of evidence for our social life prior to now—are filled with horror tales at night, while, during the day, the talk is of gossip.

Ok—so there are a whole bunch of ways we are interested in moral (and immoral) behavior: stories, songs, art, gossip…but these are all proximate mechanisms. “Proximate” is a technical term—and it's one that every piece of science journalism I have seen gets wrong—so I had better take a minute to explain it.

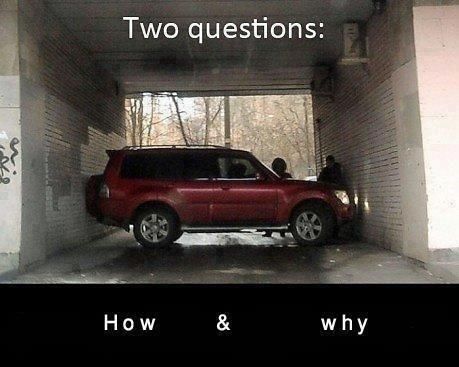

We can ask (very broadly) two types of question in behavioral science: How and Why?

How questions are the meat and drink of most of behavioral science: How does this enzyme work? How does it feel to be abandoned? How do eyes process color vision? How questions are proximate questions.

Why questions are very different—and science journalists please take note—I said "different". I didn’t say “alternatives to”. So, no more nonsense please? They add value to the how questions and suggest new avenues to research. They are just as testable as anything else. Why questions (or to give their technical term “ultimate” questions) are always cashed out in terms of evolution by natural selection. Why? Because this is the only non-super-natural mechanism that can give the appearance of design.

Ever since Darwin there has really only been one set of answers to why questions—things are the way they are because they got that way. And the way they got that way—assuming that what they are is complex functional designs—is natural selection. Descent with modification through differential reproduction. And since we realized that Mendel and Darwin belonged together, this has meant differential selection of genes in the gene pool.

But wait a minute. Doesn’t this all imply a ruthless competitiveness? Nature red in tooth and claw? Dog eat dog? Dog bites man? Man bites dog back again? Instead, what we get is Man and dog (as well as woman and cat) living in relative harmony (unless the dog gets on the couch). How is this possible? How is it that, as Steven Gould put it, our days are filled with 10,000 acts of kindness (that we don’t bother to record) and not with murder and mayhem (which we certainly do record—though not in proportion to their occurrence). How, in other words, is it possible for us—for any creature in fact—to be social?

Ever since Darwin there is one figure who has provided the basis for the answers to that question—William Hamilton. Hamilton’s rule is reasonably well known in biology: Namely a gene that underlies some altruistic trait (which could be a behavior like sharing food, or a body part like a bee’s sacrificial sting) can spread throughout the population if the cost of that behavior (C) was lower than its benefit (B) multiplied by the coefficient of relatedness (r). This is often formulated as r B > C.

Coefficient of relatedness? This is chance that two individuals share a particular gene by common descent. "r= 0.5" means a 50% chance of sharing that gene, "r = 0" means no chance, "r =1" means you are identical twins, and so on. It’s important to put it this way because saying things like “r= 0.5 means you share 50% of your genes” can get you into a confusion mighty swiftly. It also misleads some people into thinking that you will be predicted to dole out 50% of your altruism budget to your brother, 25% to your half-brother, and so on. This ain't true.

What Hamilton’s rule seems to be saying is that blood is thicker than water—and this fits with our intuitive sense that we help our family (our kin) over strangers. The problem is—that in the rush to simplify the rule (for textbooks) it’s very easy to misapprehend what it actually says.

There are four ways in which you (or any organism) can act in relation to fellow organisms

- Selfishly (you get something at their expense). This happens a lot.

- Spitefully (you both end up worse off). This happens pretty rarely. Despite how life might feel.

- Altruistically (they get something at a cost to you). More on this below.

- Mutually (you both benefit). See below

These benefits and costs are average effects, of course. A friendly dolphin who mistakes a drowning human for a young dolphin and pushes them to surface is, on average benefiting it's own kin with such helpful behavior, not being exploited by a selfish human.

Alternatively those who meet “unfriendly” dolphins simply don’t live to tell the tale.

Now—there are a lot of things to say about this list but one of the most important is that it’s easy to confuse mutualism (4) with altruism (3). Oft times when we call an action “altruistic”, what we really mean is that there was mutual benefit there. And I think that one of the reasons for our (human) confusion here is that we have a whole bunch of (proximate) mechanisms for separating out the really beneficial from the spiteful and the selfish in our vicinity. That’s the meat and drink of gossip and cautionary tales after all.

Gossip 1: “Why did he help her out?”

Gossip 2: “Oh, he’s not really being kind, it makes him feel good to help people”

This is all (biologically) wrong. Feeling good is the how the behavior works but why we evolved to feel good when we help others—e.g. why it advanced both our reproductive interests—is an ultimate question. And they shouldn’t be mixed up together. Because we are focused on whether the "how" is genuine" we confuse it with the "why".

It’s commonly thought that behaviors that benefit non family members constitute a huge challenge to Hamilton’s rule—but this is simply untrue. There are, in fact, a whole bunch of ways that direct benefits could accrue to those acting in mutually beneficial ways—and therefore be selected for in the usual way—and they usually go hand in hand with some sorts of mechanisms for enforcing compliance and punishing cheaters. Which means that we are expected to have (and do have) a whole raft of ways to spot said cheaters. One set of these is our obsessive interest in who can be trusted, whose reputation has been sullied…whether this was fair or unfair…who is gearing up to kill who if they dare go near that person again, what our Kevin didn’t ought to have said that about our Sharon at the wedding, and so on and so forth. The whole Jeremy Kyleness of it all.

In fact—the organisms don’t even have to be of the same species for mutually co-operative behaviors to spread. If you dive you can have the odd experience of watching cleaner wrasse come into cleaning stations and pick the teeth of big predators who would otherwise see them as lunch. Each gets something from the exchange. No paradox. Anyway—back to r B > C.

Hamilton’s rule only kicks in when the benefits are indirect, and his key insight was to frame this in terms of genes. Given that our (and other organisms) dispersal patterns used to be pretty viscous—e.g. we didn’t stray far from our birth group—then a lot of benefits we doled out to those around us would also benefit those who shared that altruistic gene by common descent. This would be true even if we didn’t have ways to spot kin better than average. Of course—we have a whole bunch of (proximate) ways that we use to carve out “us” and “them”. And a lot of this is the meat and drink of social psychology—describing proximate mechanisms of tribal allegiance—none of which has to be parceled out in terms of who shares most genes (or not).

However, it is all too common to see in textbooks things like “brothers help each other because they share 50% of their genes”. This is highly misleading. For one thing, folk are likely to notice that it’s commonly pointed out that we share 97% of our genes with Orangutans (say) and go “wait a minute, are you more closely related to an Orang-utan than your brother?”

Why is this wrong? Well—as the Orang-utan example shows it’s not about sharing genes it’s about having particular genes (altruistic ones) that you shared from the same source (common descent). We are all 99.99+% genetically similar. It’s that small percentage extra that varies between individual humans and it’s this space that is occupied by the genes that you share with your brother 50% of the time. Furthermore—if none of those genes code for an altruistic trait then these won’t matter to altruistic behavior. Just having a clone won’t give you a willing sacrificial slave.

So—back to Dave Fanning’s original questions. Why are we interested in murderers and miscarriages of justice? Ultimately—it’s because we evolved to have a whole bunch of mechanisms that are designed by selection to be obsessively interested in (and thus spot) potential social dangers…and those who might try to exploit those feelings to manipulate us (like crooked authorities)…and how to spot those cheaters and so on. And this interest and obsessiveness will never go away. It’s part of the how we police mutual society. And is it unhealthy to be interested in murderers? Well, maybe, but only if we try to copy them.

And now in honor of Darwin Day….

References

http://www.rte.ie/radio1/podcast/podcast_davefanningshow.xml (“True Crime 31st January 2016)

Darwin, C. (1888). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. J. Murray.

Dunbar, R. I. (2014). How conversations around campfires came to be. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(39), 14013-14014.

Gould, S. J. (1993). Ten thousand acts of kindness. Eight Little Piggies, 275-283.

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I.

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of theoretical biology, 7(1), 17-52.

Hamilton, W. D. (1975). Innate social aptitudes of man: an approach from evolutionary genetics. Biosocial anthropology, 133, 155.