Ethics and Morality

Is Greed Good?

The psychology and philosophy of greed.

Updated June 23, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Greed is the disordered desire for more than is appropriate, decent, or deserved, not for the greater good but for one’s own (perceived) interest, and often at the detriment of others and society at large. Greed can be for anything, but is most commonly for food, money, possessions, power, fame, status, attention, admiration, and sex.

The Origins of Greed

Greed can arise from early traumas such as parental absence, inconsistency, or neglect. In later life, low self-esteem coupled with feelings of anxiety and vulnerability lead the person to fixate on a substitute for the love and security that they lacked. The pursuit of the substitute distracts from the painful feelings, while its hoarding provides some degree of comfort and compensation.

Another aetiology of greed is that the trait is written into our genes because, in the course of evolution, it has tended to promote survival and reproduction. Without a measure of greed, individuals and communities are more likely to run out of resources, and to lack the means and motivation to innovate and achieve, making them more vulnerable to the vagaries of fate and the designs of their enemies.

If greed is much more developed in human beings than in other animals, this is partly because human beings have the capacity to project themselves far into the future, to the time of their death and even beyond. The prospect of our demise gives rise to anxiety about our purpose, value, and meaning.

In a bid to quell this existential anxiety, our culture provides us with ready-made narratives of life and death. Whenever existential anxiety threatens to surface into our conscious mind, we turn to culture for comfort and consolation. And today, it so happens that our culture—or lack of it, for our culture is in a state of flux and crisis—places a high value on materialism, and, by extension, on greed.

Our culture’s emphasis on greed is such that many people have become immune to satisfaction; having acquired one thing, they immediately set their sights on the next thing that comes to mind. Today, the object of desire is no longer satisfaction but desire itself.

Can Greed be Good?

Although a blind and blunt force, greed leads to superior economic and social outcomes. Unlike altruism, which is a refined capability, greed is a primitive and democratic impulse, and ideally suited to our era of mass consumption. Altruism attracts passing praise, but really it is greed that our society rewards, and that delivers the material goods and economic growth upon which our governments have come to rely.

Like it or not, our society is fuelled by greed, and without it would soon descend into poverty and anarchy. Greed lies at the bottom of every successful ancient and modern society, including the glorious Athenian and Roman empires, and political systems designed to check or eliminate it have all ended in abject failure.

Gordon Gekko, in the film Wall Street (1987), is especially eloquent on the benefits of greed:

Greed, for the lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge [sic.] has marked the upward surge of mankind.

The Nobel economist Milton Friedman (d. 2006) argued that the challenge for social organization is not to eradicate greed, but to set up an arrangement under which it does the least harm. For Friedman, capitalism is just that kind of system.

Drawbacks

But greed is, to say the least, a mixed blessing. People who are consumed by greed become utterly fixated on the object of their greed. Their lives are reduced to little more than a quest to accumulate as much as possible of whatever it is that they covet and crave. Even when they have met their every reasonable need and more, they are utterly unable to redirect their drives and desires towards other and higher things.

Greed is associated with negative psychological states including stress, exhaustion, anxiety, depression, and despair, and with maladaptive behaviours such as gambling, hoarding, theft, deceit, and corruption. By overriding pro-social forces such as reason, compassion, and love, greed loosens family and community ties, undermining the bonds and values upon which society is built. Greed may drive the economy, but as recent history has made all too clear, unfettered greed can also precipitate a deep and long-lasting economic recession.

Last but not least, our consumer culture continues to inflict severe damage on the environment, resulting in, among others, deforestation, desertification, ocean acidification, species extinctions, and more frequent and severe extreme weather events. There is a question about whether such naked greed can be sustainable in the short term, let alone the long term.

Greed and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

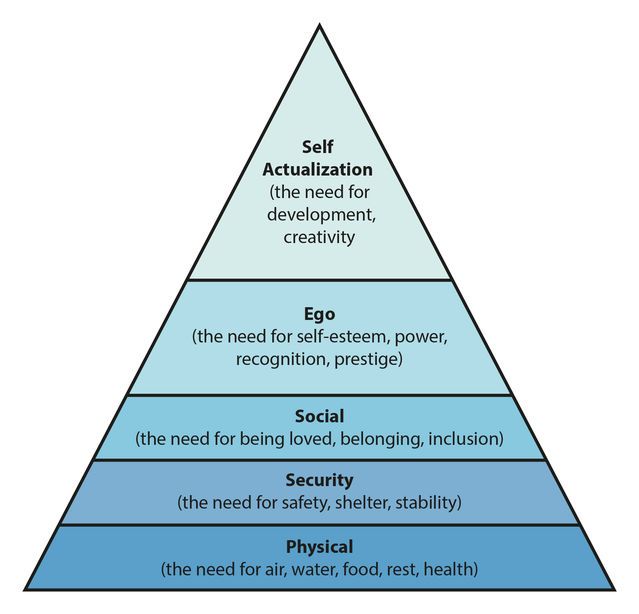

The psychologist Abraham Maslow (d. 1970) proposed that healthy human beings have a certain number of needs, and that these needs can be arranged in a hierarchy, with some needs (such as physiological and safety needs) being more primitive or basic than others (such as social and ego needs). Maslow’s so-called ‘hierarchy of needs’ is often presented as a five-level pyramid, with higher needs coming into focus only once lower, more basic needs have been met.

Maslow called the bottom four levels of the pyramid ‘deficiency needs’ because we do not feel anything if they are met but become distressed if they are not. Thus, physiological needs such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are deficiency needs, as are safety needs, social needs such as friendship and sexual intimacy, and ego needs such as self-esteem, prestige, and recognition.

On the other hand, he called the fifth, top level of the pyramid a ‘growth need’ insofar as the drive to self-actualize demands that we break beyond our limited selves to fulfil our potential as human beings. Once we have met our deficiency needs, the focus of our anxiety shifts to self-actualization, and we begin, even if only at a sub- or semi-conscious level, to contemplate our bigger picture.

The problem with greed is that grounds us on one of the lower levels of the pyramid, preventing us from ever reaching the pinnacle of growth and self-actualization. Of course, this is the precise purpose of greed: to defend against existential anxiety, which is the type of anxiety associated with the apex of the pyramid.

Greed and Religion

Because it removes us from the bigger picture, which is God, greed is roundly condemned by all the major religions.

In the Christian tradition, greed, or avarice, is one of the seven deadly sins, a form of idolatry that forsakes things eternal for things temporal. In Dante’s Inferno, the avaricious are bound prostrate on a floor of cold, hard rock as a punishment for their attachment to earthly goods and neglect of higher things.

In the Buddhist tradition, it is craving that keeps us from the path to enlightenment. Similarly, in the Hindu Mahabharata, when Yudhishthira asks to ‘hear in detail the source from which sin proceeds’, Bhishma replies in no uncertain terms that it is from covetousness that sin proceeds.

In Book 12, Section 158 (the Mahabharata is the longest poem ever written), Bhishma tells Yudhishthira:

From covetousness proceeds sin. It is from this source that sin and irreligiousness flow, together with great misery. This covetousness is the spring of also all the cunning and hypocrisy in the world. It is covetousness that makes men commit sin. From covetousness proceeds wrath; from covetousness flows lust, and it is from covetousness that loss of judgment, deception, pride, arrogance, and malice, as also vindictiveness, shamelessness, loss of prosperity, loss of virtue, anxiety, and infamy spring, miserliness, cupidity, desire for every kind of improper act, pride of birth, pride of learning, pride of beauty, pride of wealth, pitilessness for all creatures, malevolence towards all…

The Fear

The song The Fear (2009) by singer and songwriter Lily Allen is a modern, secular version of this tirade. Here are a few choice lyrics by way of a conclusion:

I want to be rich and I want lots of money

I don’t care about clever I don’t care about funny

…And I’m a weapon of massive consumption

And it’s not my fault it’s how I’m programmed to function

…Forget about guns and forget ammunition

‘Cause I’m killing them all on my own little mission

I don’t know what’s right and what’s real anymore

And I don’t know how I’m meant to feel anymore

And when do you think it will all become clear?

‘Cause I’m being taken over by The Fear

Read more in Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions.