Fantasies

Ray Bradbury's Case for Truth Through Freedom of Thought

The science-fiction writer believed new ideas will not contaminate or corrupt.

Posted March 1, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Ray Bradbury's 1953 novel 'Fahrenheit 451' is often thought to be about book burning, but is actually about freedom of speech and thought.

- Bradbury was a fierce opponent of thought control, including "political correctness."

- Bradbury believed the answer to objectionable ideas is not censorship but better ideas.

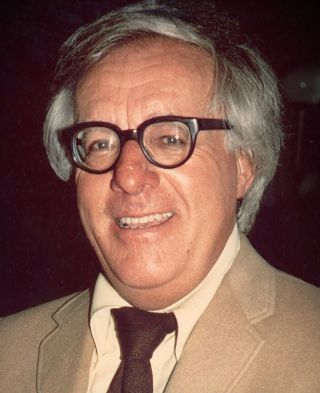

One of the 20th century’s most remarkable—and in some respects, unlikely—American defenders of free speech was the science-fiction/fantasy writer Ray Bradbury. Author of the books The Martian Chronicles and Dandelion Wine, Bradbury is perhaps best known for his 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451, a title derived from the purported temperature at which book paper ignites. Ostensibly about book burning, Bradbury later identified the novel’s principal target as political correctness, which he referred to as “the real enemy these days”—control not only of what people can read but also what they can think. So lyrical were the grounds of Bradbury’s opposition to the policing of thought that many contemporaries might initially fail to appreciate their full relevance and power.

Ray Bradbury and the freedom of ideas

Bradbury was born in 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois, and moved with his family to California when he was 14 years old. As a teenager, he traveled to Los Angeles on roller skates, meeting writers through the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society and striking up friendships with stars such as George Burns. He published his first story at age 17 and was writing full-time by 24.

Bradbury drafted the first version of Fahrenheit 451 in UCLA’s library, where he paid an hourly fee for the use of a typewriter. At age 34, he wrote the screenplay for John Huston’s film Moby Dick. Over the course of his career, he published nearly 600 short stories and 30 books, garnering a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, winning the O. Henry Prize twice, and receiving the National Medal of Arts before his death in 2012.

Unlike many free speech advocates, Bradbury was no friend of higher education. Having never attended, he branded college “very dangerous” because it exposed the young to professors who are “too opinionated, too snobbish, and too intellectual.” He regarded the learned intellect not as a fount of creativity but a threat to it. Such learning could alienate students from their own “basic truth,” by which he meant “who you are, what you are, and what you want to be.”

Too much thinking, Bradbury held, could lead to lying, a propensity especially common among intellectuals, who often make up reasons for things they say and do. To counteract this tendency, Bradbury kept a sign over his typewriter for much of his writing career that read, “Don’t think,” reminding him to “tell the truth, all the time.”

Nor did Bradbury believe in curricula. Instead of entering the library with a list, he approached shelves, took down books, and opened them, sometimes “falling in love immediately.” When such magic did not happen, he simply placed each book back on the shelf and moved on. What mattered to Bradbury was not what the experts told people they should like but what the text did or did not evoke in him. “You can only go with loves in this life,” he said. Bradbury found such love in the writings of Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. “Without Burroughs’ Tarzan and John Carter,” he admitted, “I would never have grown to be twelve feet tall and taken off for Mars,” explaining that “you must galvanize people and make them want to be completely alive and live forever.”

The principal character of Fahrenheit 451, Guy Montag, is a “fireman” who instead of extinguishing blazes makes his living burning down houses that contain forbidden books. While writing the book, Bradbury realized that he was Montag—that he harbored the same destructive impulses as a totalitarian. Yet by bringing such impulses out into the open, Montag discovers that he is burning “not just books but ideas,” that he can learn to read anew, and that by reading well, he can relearn how to be alive. As a result of his odyssey, Montag renounces his profession, becoming not a destroyer of ideas and the books that contain them but a destroyer of the destroyers who nourishes the ideas that provide him with new life.

Bradbury’s devotion to ideas was grounded in his cosmology. “In this part of the universe,” he declared, “God has awakened on this planet and shaped himself the way we are shaped.” We are, he argues, “the flesh of the universe which wishes to know itself.”

Bradbury believed that he and every human being could be part of the universe waking up, looking around, and saying, “Hey, this is remarkable; look at this.” Each human being has the senses, the intelligence, and the imagination, and each one can discover, “I’d like to keep this gift going.” Where others have seen a conflict between religion and science, Bradbury saw each as a side of the same coin, both ultimately ending in mystery. To Bradbury, the myth of incarnation is ultimately no more or less mysterious than gravity.

Every human confronts the same basic questions.

How did we get here? Where did we come from? Where are we going? The ultimate answers, Bradbury believed, will always elude human beings, but their pursuit should be a source of enthusiasm in life, bringing joy and inspiring creativity. The goal in life, he thought, is not so much to follow the one right path but to do what we truly love, and he believed that appropriate fields of thought and work exist for everyone. Some vocations may be highly idiosyncratic, but others may be widely shared or even universal, such as the love of raising children. Even the most sophisticated technologies imaginable are just another answer to basic human questions about how to build character and societies.

To those who would suppress books and ideas, Bradbury counters that human beings are, above all, the ideas with which we live. If we suppress the ideas of others, we eliminate possibilities, possibilities to learn, and possibilities to dream. And in so doing, we impoverish ourselves and everyone else.

“There’s room in your head for all of it,” Bradbury said. “It’s not going to contaminate or corrupt you or anyone else.” On the contrary, this panoply can enrich us by showing us other ways of seeing. Even if we don’t ultimately adopt them, they help us better understand and appreciate our own vantage points. Diversity—intellectual, emotional, and imaginative—is something not to be shunned but embraced, Bradbury held, because only through such new experiences and ideas can we come more fully to life.