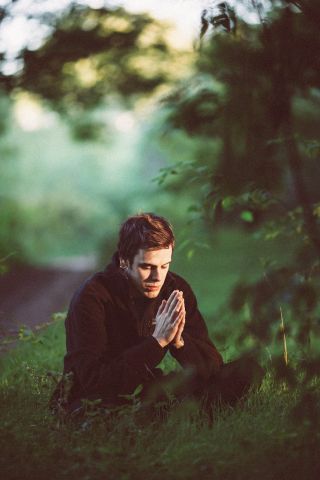

Meditation

Two Ways to Put the Power of Your Mind to Use

New research shows how to unlock the hidden power of meditation.

Posted November 14, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Meditation is a practice that intervention research shows can benefit emotional well-being and mental health.

- New research suggests that meditation reduces "attentional blinking," which is zoning out new information.

- You can put meditation to work for you by avoiding going through your day on autopilot.

Perhaps you thought you could never become a good meditator. Your mind is filled with other concerns, and it hasn't worked for you every time you've tried it.

You might also think it's a bit "out there" and best reserved for those who only practice certain religions—not yours.

However, maybe you've read about the potential benefits of meditation for mental health and its related process of mindfulness. This thinking method puts you squarely in the "here and now" of your experiences.

Again, though, how would you ever fit this into your hectic life? You might even have a smartwatch app that tells you to take a mindfulness minute. You ignore it and move on to all the emails that await you or a boss standing at your door, telling you to move on.

Yet, there is so much hype about meditation, and even more, you may have come across scientific studies that demonstrate its many benefits for mental health, including reductions in anxiety and depression. For those times when you feel down, might it be worth giving it a try?

What Makes Meditation Work So Well

According to new research by Universidad Villanueva's Pablo Roca and colleagues (2023), there are across-the-board benefits to meditation, including reduced stress, anxiety, depression, psychological distress, and low feelings of well-being. These findings almost sound magical, yet they continue to emerge from well-conducted controlled trials.

A lingering question that the Spanish researchers ask is, "Why?" What could account for meditation's benefits in this wide range of unpleasant psychological states?

Prior studies on mindfulness, a practice that brings you into the "here and now," might have its effects through the changes it produces in attentional biases or the tendency to focus on experiences and events that you interpret as "positive stimuli." For example, looking at a person near you who seems angry at you for no apparent reason is more distressing than engaging your attention on someone who's giving you a friendly glance, so you're trained to look at the friendly face.

However, Roca and his colleagues believe that it's not just a bias toward the negative that can produce the kind of mental distress that meditation alleviates. More generally, meditation reduces "attentional blinking," the tendency to zone out when processing new information. Through meditation, they propose that you become better at "engaging with negative, positive, and neutral stimuli equally, rather than avoiding or focusing on certain experiences."

The Case for Attentional Blinking

The Spanish researchers tested their model by measuring whether they could improve (reduce) attentional blinking in participants exposed to interventions using meditation (vs. control). In the attentional blink task, participants were asked to identify emotions on faces presented via computer images in rapid-fire order. The more emotions they could identify, the lower their tendency to blink.

The interventions themselves consisted of two forms of meditation-inducing therapy administered in the form of standard eight-week treatments, with 30 participants per group, plus another group of controls. The outcome measures included emotion regulation and well-being.

As they predicted, participants receiving meditation therapy benefited from these two outcomes, primarily due to their greater ability to avoid attentional blinking. As the authors concluded,

Meditation practice improves attentional processing, reducing the propensity to 'get stuck' on certain stimuli and improving the allocation of attentional resources.

Putting Meditation to Work For You: Two Simple Steps

If meditation is indeed what the authors call the "entry door" to better mental health, it achieves this key effect, the findings showed, through a reduction in attentional blinking. How can you take advantage of this simple but effective method? Is it possible you could become good at meditating after all?

The first step is to avoid going through your day running on autopilot. The more you can bring yourself into the moment, using whatever cues work for you, the more you can get your attention away from the stresses in your life that can lead to negative emotions that can erode your well-being.

Watch one of those television shows in which you find yourself zoning out. Ensure you follow the sequences of events going from A to B to C so you don't "blink" away from B. Give yourself practice in noticing small shifts in the emotional expressions of the people around you.

At that point, you can move on to the second step, in which you put those observations to use. In the Roca et al. study, one form of meditation involved mindfulness, in which you reframe your perceptions more positively. The second intervention used compassion therapy, in which participants learned to have empathy toward others, including self-compassion or empathy toward themselves.

To sum up, rather than view meditation as a practice that needs to rob crucial seconds, minutes, or hours from your day, these new findings suggest easy ways to incorporate them into your life. Rather than see them as subtracting, you can now view meditation as a way to add to your ability to get through your day and make it more fulfilling.

References

Roca, P., Vazquez, C., Diez, G., & McNally, R. J. (2023). How do mindfulness and compassion programs improve mental health and well-being? The role of attentional processing of emotional information. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 81, 1–10.DOI: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2023.101895