Addiction

The Evolving Landscape of Addiction and Where Processed Food Fits

The landscape of addictions is changing.

Updated July 18, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- The DSM-5 has yet to recognize food-related dependence as a non-substance behavioral addiction.

- Caffeine and ultra-processed foods have been found to have similar addictive properties as drugs and alcohol.

- Americans who are impacted by food deserts may be more likely to struggle with food dependence.

The landscape of addictions is changing.

Historically, whenever the topic of addiction or substance abuse was being discussed, the thought of drugs and alcohol addiction immediately came to mind. This viewpoint has since changed over time for a few reasons.

First, behavioral (or process) addictions have emerged and have been recognized by the American Psychological Association. For example, gambling was the first non-substance behavioral addiction to be recognized in the DSM-5 in the year 2013. Prior to this point, gambling problems were known as “pathological gambling” and not yet classified as an addictive disorder.

As research has grown and progressed, we have identified that other compulsive behaviors, that do not include drugs and alcohol, can meet the criteria in place by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)—producing substance use disorder. Within this category, researchers have found addictive-like properties with the use of caffeine or the foods we commonly provide to our children—ultra-processed foods. Unlike drugs and alcohol, ultra-processed foods have no restrictions or laws in place to prevent or limit their consumption. Despite the lack of restrictions and rules in place, the addictive properties of ultra-processed foods can result in detrimental health impacts long term—just like smoking tobacco can.

Food is ubiquitous and necessary for survival; however, the emergence and proliferation of ultra-processed foods have led to an increase in compulsory eating behaviors. The prevalence of dependence on processed foods is roughly 20% according to a meta-analysis that utilized the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS).1 This statistic is low compared to the prevalence of addiction in users of controlled substances like heroin (86%) or methamphetamine (68%). Unlike controlled substances, which have fewer users overall, almost all Americans consume ultra-processed foods and have easy access to them. With this, there is the potential that 65 million people may struggle with overconsumption of processed foods.

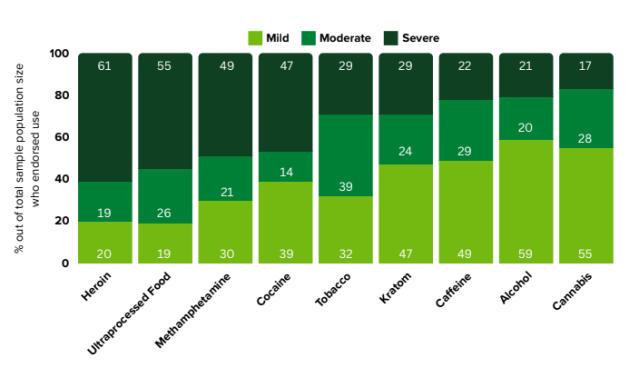

To clarify and understand the impact of substance use disorders, a comprehensive report was conducted to compare the substance use disorder profiles of various substances. These substances ranged in their prevalence of use and whether or not they were scheduled or illicit. When we look across multiple studies2-6 of these different substances, and assess the criteria used to define whether or not the substance can result in substance use disorder (according to the DSM-5 criteria), some striking findings emerge. When we look at the likelihood of a severe addiction (as opposed to mild or moderate) to the substance developing, ultra-processed food ranks just behind heroin.

Though dependence on processed foods is not yet recognized by the DSM, the YFAS uses symptom endorsement to determine the severity of the use disorder—similar to the DSM.2 The severity of compulsive eating was quantified using the YFAS based on the number of symptoms explained. It was found that 55% of Americans were categorized under a “severe addiction” (6+ symptoms). This data was then compared to other substances of abuse, and the only substance with a higher rate of “severe addiction” was heroin at 61%. Tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, and cannabis all had less than 30% of users reporting a “severe addiction.”3

Outside of severity, we see diminished mental and physical health for certain substances more than others. Some of these are acute, whereas some manifest over time. A recent review looked at the prevalence and factors influencing suicidal ideation, attempt, and completion, and found a significantly higher prevalence of suicidal ideations and/or suicide attempts in the population of individuals who were abusers of heroin.7 On the other hand, with substances like tobacco and ultra-processed foods, the effects on physical and mental health are often cumulative over time. With ultra-processed foods, we see a correlation between high intake and an increase in BMI—which may contribute to adverse health outcomes.8 From another perspective, we can look at how the categorization of an overweight or obese BMI affects mental health—similarly to those with substance abuse disorder. Research shows those who have an obese BMI also tend to struggle with issues related to their mood, self-esteem, quality of life, and body image.9

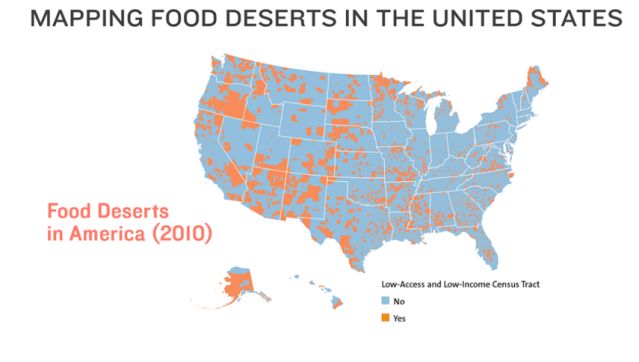

When we look at the range of substances out there that are being abused, we need to consider multiple factors—including the relative risk of developing a severe addiction to it. The evidence shows that some substances that are not mentioned in diagnostic criteria, like food, can still have detrimental consequences. The struggle with ultra-processed food in particular is that some Americans have abundant access to ultra-processed foods with limited access to nutritious foods. Much like how the addiction landscape is evolving, the dietary landscape can vastly differ in a different geographic or socioeconomic region. Approximately 13% of Americans live in a food desert, which means they live in an area with limited access and opportunities to secure affordable and healthy foods that are both convenient and safe.10 This means that those falling into the cycle of food dependence may not have the means or ability to adopt healthier habits. The prevalence of food deserts is an ongoing issue seen in communities that are rural, low-income, and have limited public transportation.

In conclusion, the science shows us drastic similarities between substance use disorders of drugs and alcohol and dependence on processed foods. Although the official diagnosis of food dependence currently remains unrecognized by the DSM criteria, research supports the idea that food can be addictive and result in deleterious health complications. When assessed through the YFAS, severe food dependence was found in over half of Americans, which was a much higher statistic than the other controlled substances studied. Geographically, food desert communities are at greater risk of developing dependence on processed foods based on their ability to easily access ultra-processed foods. These foods are found to trigger similar neurocircuitry to heroin, and Americans have built similar tolerance to these foods as those do with substances of abuse.

Whilst the American Psychology Association has yet to officially recognize food dependence as part of the DSM-5, the current research supports the idea that certain foods can be addictive, and its detrimental impact over time should not be disregarded. The average American’s access to ultra-processed foods increases each day as scientists pinpoint new ways to make food more desirable to the consumer. As the American food supply grows, the number of individuals struggling with overconsumption of processed foods is likely to continue rising. In order to stop the vicious cycle of food dependence, we must first recognize it as an issue and increase awareness among those impacted.

References

1. Praxedes, D. R. S.; Silva-Júnior, A. E.; Macena, M. L.; Oliveira, A. D.; Cardoso, K. S.; Nunes, L. O.; Monteiro, M. B.; Melo, I. S. V.; Gearhardt, A. N.; Bueno, N. B., Prevalence of food addiction determined by the Yale Food Addiction Scale and associated factors: A systematic review with meta-analysis. European eating disorders review : the journal of the Eating Disorders Association 2022, 30 (2), 85-95.

2. Wiedemann, A. A.; Carr, M. M.; Ivezaj, V.; Barnes, R. D., Examining the construct validity of food addiction severity specifiers. Eating and weight disorders : EWD 2021, 26 (5), 1503-1509.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2022). National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2022. Retrieved from https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/

4. Sweeney MM, Weaver DC, Vincent KB, Arria AM, Griffiths RR. Prevalence and Correlates of Caffeine Use Disorder Symptoms Among a United States Sample. J Caffeine Adenosine Res. 2020 Mar 1;10(1):4-11. doi: 10.1089/caff.2019.0020. Epub 2020 Mar 4. PMID: 32181442; PMCID: PMC7071067.

5. Shmulewitz D, Stohl M, Greenstein E, Roncone S, Walsh C, Aharonovich E, Wall MM, Hasin DS. Validity of the DSM-5 craving criterion for alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, and non-prescription use of prescription painkillers (opioids). Psychol Med. 2023 Apr;53(5):1955-1969. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721003652. Epub 2021 Nov 1. PMID: 35506791; PMCID: PMC9096712.

6. Smith KE, Dunn KE, Rogers JM, Garcia-Romeu A, Strickland JC, Epstein DH. Assessment of Kratom Use Disorder and Withdrawal Among an Online Convenience Sample of US Adults. J Addict Med. 2022 Nov-Dec 01;16(6):666-670. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000986. PMID: 35220331; PMCID: PMC9402806.

7. Khanjani MS, Younesi SJ, Abdi K, Mardani-Hamooleh M, Sohrabnejad S. Prevalence of and Factors Influencing Suicide Ideation, Attempt, and Completion in Heroin Users: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Addict Health. 2023;15(2):119-127. doi:10.34172/ahj.2023.1363.

8. Beslay M, Srour B, Méjean C, et al. Ultra-processed food intake in association with BMI change and risk of overweight and obesity: A prospective analysis of the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. PLoS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003256. Published 2020 Aug 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003256.

9. Sarwer DB, Polonsky HM. The Psychosocial Burden of Obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45(3):677-688. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2016.04.016.

10. Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2021). Food Deserts in the United States. Retrieved from https://www.aecf.org/blog/exploring-americas-food-deserts#:~:text=How%20many%20Americans%20live%20in,research%20report%2C%20published%20in%202017.