Free Will

Do You Have Free Will?

There is no sharp dividing line between voluntary and involuntary behaviors.

Posted August 20, 2018 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Do you think of yourself as the author of your own actions? A free agent? Completely and all the time?

Or perhaps you have had moments in which you think, “I don’t know why I just said that,” or, “I don’t know what came over me when I did that!”

My patients with psychiatric disorders more readily admit that there are times when they definitely do not feel in control of their thoughts, emotions, speech and actions. It’s frightening and dismaying for them.

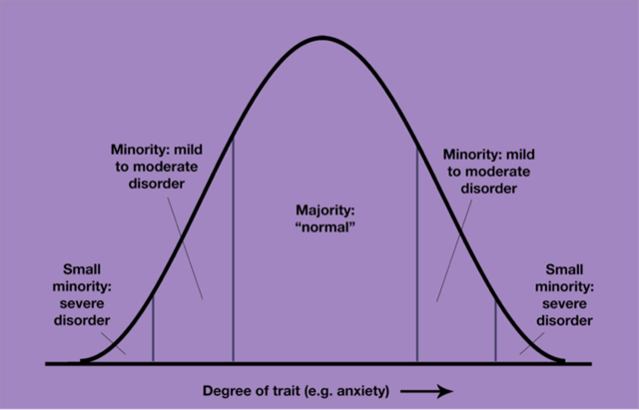

Most mental disorders can be understood as ends of a continuum of normal human traits,1 as shown in this graphic.

Parents regularly bring their misbehaving, moody or unmotivated teenager for assessment “to figure out” if the teen “has a mental disorder or just a behaviour and attitude problem.” They ask me if the problem is that they “can’t—or just won’t” behave better, stay calmer or work harder.

It’s a practical distinction, but a false dichotomy. There is no sharp dividing line between voluntary and involuntary behaviours.

No brain is untethered from its physical determinants

If there were such a thing as truly free will—then "mind stuff" would have to be categorically separate from the rest of the physical stuff in the universe. Such a view of the world—as divided between mental and physical phenomena, is referred to as dualism. For dualism to be correct, all of science would have to be incorrect. The mind comes from the brain and nothing but the brain.

The brain is the product of genes and environment interacting over the history of the life of the animal.2 The brain is shaped by its interaction with its environment—i.e., experience. That is how learning occurs.

Every brain is primed or biased by its unique genetic predisposition to respond slightly differently to the environment, and to learn differently. That’s what temperament is. For example, people differ in their capacity for self-control. Upbringing also influences self-control, as do practice and a person’s habits. Too much self-control can be as impairing (and involuntary) as too little of it.

So now think about it: since we are entirely the product of our genes and our environment, where does free will enter the picture? Believing in true free will would entail taking the position that within each of our brains there exists some sort of independent entity unaffected by those factors, like a little executive steering the brain, able to freely ‘decide’ when and how to act. This executive would have to be entirely independent of all the genetic and environmental factors that have shaped the brain’s microscopic connections up to that moment. We would have to imagine such an executive sitting in splendid isolation, entirely aloof from the rest of the brain and impervious to all its determining influences.

Where am "I"?

Yes, it certainly feels like I act executively much of the time. But what and where exactly is this “I”? There are parts of the brain (the prefrontal cortex) that are relatively more executive in their functions. But even these hierarchically higher regions are dependent on and shaped by input from lower, more primitive parts of the brain. The brain consists of interdependent regions in a reverberating circuit.3 There is no absolute, separate executive. The sense of executive self is an elaborate illusion.

Our brains are complex assemblies of particles interacting with other assemblies of particles in our little corner of the universe. Exceedingly complex systems like the human brain behave in extraordinarily complex and unpredictable ways—not like a simple billiard ball model. For this reason, trying to predict exactly how a person will respond to a situation is practically impossible—even if we had an unimaginably powerful computer that could compute all the variables.

In that sense—the uniqueness and unpredictability of each decision and action, a brain does possess something that in practice resembles free will. We might as well regard ourselves as having free will. But it is not true free will in pure principle.

A matter of degree

Brains that are affected by mental illness, damage or developmental delay lose much of their flexible complexity—they become less free in their will. Thought patterns and behaviour become more rigid, distorted, reactive, and sometimes even stereotypic. Responses are less cognitively controlled and instead more determined by emotion, habit, or impulse.

But remember, what constitutes a mental disorder is often a matter of degree—being further along the continuum of a normal human trait. So those questions we were considering about “mental disorder or attitude” and “can’t or won’t” might need to be answered in shades of grey rather than black or white. I try to keep this in mind with those difficult teens or anyone else with mental health concerns…and in fact when evaluating all human behavior.

So, free will is a matter of degrees of relative freedom—degrees of flexibility. But the brain’s decision-making ability is never completely untethered from its recent or distant determining factors.

Some people find this realization depressing—that our will is never truly free. But I find the workings of this product of natural evolution awe-inspiring and humbling. It’s also empathy-inducing, especially when considering those who face mental illness.

1. Even clearly abnormal conditions that are not just accentuations of normal human traits, such as head injuries, developmental delay, dementia, or schizophrenia, have a range of severity, with the mildest versions being practically indistinguishable from normality.

2. And the genes an animal inherits at conception are the product of evolution – itself shaped by gene-environment interaction over eons of time.

3. Or cybernetic loop.