Identity

Why You Don’t Feel Like Yourself

How identity can change with misattributed parentage experiences.

Posted January 7, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Going through something difficult can change a person.

- A mismatch in autonomy can change our allegiances, resulting in feeling rejected or pushed out.

- To regain identity after a disruption, allow for new experiences and engage in identity-building activities.

Going through something difficult changes us. It makes us feel unlike ourselves and different from those around us. It can happen from grief, like losing a loved one, or the end of a relationship. It can also happen when we change at a different pace from the important people in our lives, creating a mismatch in differentiation or autonomy. Our allegiances can change, resulting in feeling rejected or pushed out, and if that happens, we can often feel a shift around who we are, our identity.

Identity develops in two stages, first through social identification and second through personal identification. In social identity, we find meaning in the groups we belong to, both those we seek out and those we are born into. In fact, our family of origin is the first social group we belong to, and perhaps the origin of the old adage "blood is thicker than water." Allegiance to a group is generally defined by the acceptance of the group norms to the exclusion of those who are not considered part of the group; outsiders. When we see ourselves reflected in the group, we begin to embed personal identity, the stable sense of self that endures over the lifespan and consists of the individual parts that make the whole.

We don’t feel like ourselves when those parts change abruptly, thereby disrupting our identity and making us feel we don’t know ourselves or where we belong. This is especially true in misattributed parentage experiences (MPE) when people learn later in life their conception is the result of an affair or sexual assault (non-paternal event—NPE), late discovery adoptee (LDA), or donor conception (DCP). The experience of learning you are no longer biologically related to at least one side of your family significantly disrupts identity by ripping away the previous ethnic, racial, and cultural identifications that comprised the first parts of social identity. Not to mention the personal ties of individual relationships nurtured within that social context.

The first step to regaining a foothold of identity after such a disruption is to allow the possibility of new experiences. Too often we feel desperate to regain what has been lost, to return to who we were before the unwanted change, but that is not realistic. All life experiences trigger changes that we adjust to. Unwanted changes are felt more severely due to their level of gravity versus the low-level changes that allow us to adapt at a slower pace and therefore more easily. Allowing the possibility of new experiences facilitates the emotional adjustment that accompanies identity confusion. Healthy mourning includes open acknowledgment of the change while simultaneously creating new experiences and meaning in relationships.

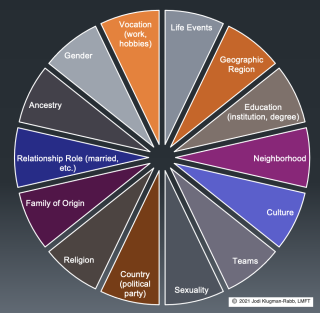

The second step involves actively engaging in activities that build identity across multiple dimensions, including ancestry, culture, religion, geographical region, nationality, hobbies, etc. (see Identity Dimension wheel). This means intentionally trying out social identities and asking oneself how this feels and how it helps. Try on cultural traditions, listen to the music, watch the films, and seek out groups in your area that are organized around that particular cultural heritage. Eric Erikson identified the single developmentally expected identity crisis that occurs in adolescence when personas are actively tried on and discarded. Adjusting to unwanted life events is helped by re-enlisting the same effort.

We feel different after major life events because we are different. Identity is relatively stable over time but is also fluid in that it responds to social identification and life experiences. You may experience others responding to your identity crisis with dismissal or possibly even hostility. This seems to be the case when those people don’t have the personal experiences of loss and resulting identity changes to empathize. They may also feel triggered for their own unwanted and as yet unresolved pain. In any case, their response is born from their issues and is not a personal reflection of your identity or worth.

References

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Faber & Faber.

Nevzlin, I. (2019). The Impact of Identity: The power of knowing who you are. Irina Nevzlin.

Voorhees, B., Read, D., & Gabora, L. (2020, April 1). Identity, kinship, and the evolution of cooperation: Current Anthropology: Vol 61, no 2.