Trauma

I May Not Be the Right Therapist for You

Choose a trauma therapy approach and not a modality.

Posted July 22, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Every week, I am contacted by people from around the world desperate to find help. They’ve tried many things with no lasting relief.

Most do not have good information about trauma. Most are so overwhelmed with stress and pain that they struggle even to make the effort to find a therapist.

I write this post to those who are in such a place, trying to figure out how to get the help they need after trauma. I spent a decade in that place and I know a few things about it!

At the age of 20, I began therapy with a clinical psychologist. Even though it would have been easy to recognize from life events that I have a history of complex trauma, the word trauma was never mentioned, not once. I had no sense of progress, even after several years. But I was miserable and didn’t know what else to do. So I continued.

Five years later, my brother died unexpectedly. Things got much worse for me, despite my ongoing therapy. Eventually, I decided to find another therapist, also a clinical psychologist, with whom I did nearly five additional years of psychodynamic therapy. All to no avail.

I felt flooded much of the time, hopeless, with a lot of triggers and an ongoing sense of fear—what today I know was severe sensory embodied trauma symptoms. Not once in that second five years was the word trauma mentioned.

I have no complaints against these two therapists. They did what they were taught to do, which was dynamic verbal psychotherapy. Perhaps that works for some people, but it sure didn’t work for me.

I was suffering from obvious PTSD symptoms, and spent 10 years in the wrong kind of therapy, thinking that I was doing the best that I could for myself. Since I was in therapy and not getting better, I blamed myself. Maybe something was wrong with me. Maybe I was not trying hard enough. Maybe if I really wanted to get better I would get better. These unnecessary questions were added to the original self-doubts that always accompany trauma.

Why I May Not Be the Right Therapist for You

Here is what I wish someone had told me in that dark decade; and what I tell those who contact me today:

1. There is no one trauma intervention that helps all. Sustainable trauma treatment is a set of interventions that target different aspects of wellbeing. Together they can have great impact, but alone, the results of any one of them are inconsistent and limited in duration.

Most people seem to be looking for the one thing that will make their pain/trauma/injury go away. There is no such thing–most certainly not one that will work for everyone all the time.

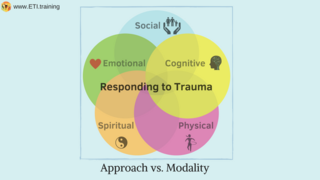

The injury of trauma is complex, a shock, of sorts, to all systems. These include: (1) Cognitive – trauma affects ability to process thoughts and make good judgments; (2) Physical – it affects our muscles, joints, metabolism, temperature, sleep, immune system, appetite and weight, etc.; (3) Emotional – many survivors loop endlessly through emotions of shame, guilt, fear, anger and pain; (4) Spiritual – trauma affects our worldview, our understanding and meaning of life, society, and the world; and (5) Social – trauma affects relationships with spouses, family, friends, colleagues and strangers.

The response must also then be complex as well and engage emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual and social aspects of existence. That cannot be done by only sitting and talking to a therapist once a week. Trauma integration requires daily routines that address diverse aspects of being.

2. Consider whether you feel a sense of personal connection to your therapist or a potential therapist. The fact that a therapist is well-known or did great work with an acquaintance does not mean this is the right therapist for you. With few exceptions, trauma is caused in relationship to someone else. In all cases, its consequences have big impacts on relationships. A sense of good connection to your therapist, a safe and contained relationship, is important for moving on from the wounds of trauma.

Even a high-quality therapeutic relationship has a certain element of chemistry. It’s not possible for any therapist, no matter how good, to achieve that with every client. You will know a therapist is right when you feel deeply cared for and in the center of attention of your therapist, most of the time, when you are in sessions. Over time, you will feel a growing sense of trust, both in him/her and yourself.

3. Find, if you can, a therapist who uses a trauma approach, not a modality. I am often asked what it is the best modality to treat trauma. There is no one modality that helps everyone! Recognizing this, and letting go of the endless search for the perfect modality is for many survivors an important step towards integration.

A therapist who truly understands trauma and the requirements of moving on from it understands the limitation of any one modality and will not hesitate to cooperate with other practitioners (neurofeedback, diet and nutrition, occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, massage and acupuncture, etc.) as needed to address your specific needs.

If a therapist promises “full healing and recovery," “full reversal of trauma," or feeling better in 10 sessions, I’d suggest that you keep looking, especially if you have a history of multiple traumas.

Trauma takes things away from us and some can’t be returned, ever. For some survivors, the losses are physical, and tangible, such as people we loved or a body that once functioned perfectly. For others, the losses are emotional or intangible, such as a sense of uncomplicated wholeness, pristine memories of beloved times and places. Either way, coming to terms with irreversible loss is an essential part of trauma integration. Anyone who implies otherwise makes the journey ultimately harder for survivors.

4. What should a trauma approach include? A trauma therapy approach should target all five aspects of your wellbeing (emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual and social). Different therapists do this in a variety of ways.

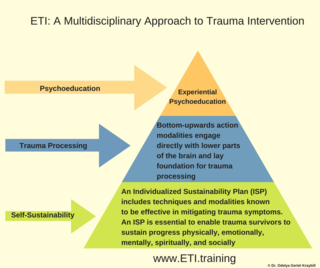

I've become a strong advocate of a comprehensive strategy. I pursue this with the Expressive Trauma Integration approach which grew out of my own life experience as a survivor and later academic research. The Expressive Trauma Integration framework has three pillars:

(A) Experiential psychoeducation about the biological, emotional and physical effects of trauma on survivors and families (individual trauma) and communities (communal trauma).

(B) Experiential modalities (bottom-up) that target the lower parts of the brain and help with relaxing/engaging the hyper/hypo nervous system responses.

(C) Self-sustainability—Setbacks following encouraging progress are common after trauma. This means that many of the challenges that life brings to everyone emulate the dynamics of trauma. Stress of any kind can easily send survivors into Withdrawal (stage #3 in the ETI roadmap after trauma).

It doesn’t mean survivors are necessarily destined for a harder life. It means that we must be more conscientious and strategic in the approach we use to manage sustainability. Part of therapy should be devoted to figuring out and revising routines to accomplish this.

We cannot expect treatment for an injury that affects all aspects of wellbeing to be addressed only by working with emotional and cognitive symptoms. We also have to address physical, spiritual and social aspects in the therapy room and beyond, all the time.

One way I seek to address this reality beyond the therapy room is by working with clients to establish an Individual Sustainability Plain (ISP), made up of practices tailored to the survivor’s unique situation. The goal is to establish a sense of safety, stability, self-efficacy, and connection to resources (from before the trauma and after it).

Such routines should incorporate practices demonstrated to be effective in mitigating trauma symptoms and include bottom-up modalities and top-bottom modalities. (Look for a therapist experienced with both, and capable of selecting which to use and when.) These can be drawn from self-compassion practices, sensory and bilateral integration, cognitive processing and behavioral modifications (top-down), expressive arts, movement and sports, diet and nutrition, brain-training and neurofeedback.

5. Review your expectations. I think that many survivors and therapists are mistakenly pre-occupied with ending the symptoms and the pain. No one gets through life without enduring sadness, pain and injury.

There is no way to undo trauma, just as there is no way to un-do the disappointments, failures, and griefs that life brings. But we can nevertheless live rich and meaningful lives, that are not over-shadowed by our pain, most or all the time.

I think I could have saved a lot of time, effort, needless pain, money, and many other resources if I had been told that much of the work of moving on from trauma is about coming to terms with the fact that this happened to me, and in some ways some of the pain is here to stay.

I spent years determined to learn everything I could about trauma so I could end the pain. Eventually, I realized that moving on after trauma is not about leaving the pain of the past forever behind, but rather about being able to integrate that pain as only one part into the larger experience of my life.

When we are in intense pain, it feels like we are the only ones, that it will last forever, and that we would do almost anything to end it.

No therapist and no modality can fully remove this pain. What they can do is help you expand your capacity to endure this pain, increase your ability to discover and reconnect to sources of joy, and reposition your understanding of life in such a way that trauma does not feel like your entire experience of reality.