Infidelity

My Partner Cheated on Me — Should I Try to Make It Work?

Compelling research on how people decide whether to stay or go after infidelity.

Posted October 12, 2017

"Infidelity raises profound questions about intimacy." —Junot Diaz

While there is a lot known about the factors that contribute to or prevent infidelity, there is less understanding, from the perspective of someone dating the partner who has cheated, of what goes into the decision to stay and try to make it work or to split up and try to move on. This can be a very clear-cut decision, and sometimes being cheated on ends up telling us what we needed to know. But it can also be full of ambivalence, indecision, and feelings of loss.

A Cognitive Science Perspective

To explore the ins and outs of this crucial decision-making process, Shrout and Weigel (2017) developed research to look at the steps that contribute to decision-making when partners in a committed relationship are faced with infidelity from the other partner. Their study focused on cognitive psychological factors, while acknowledging the generally more intuitive importance of the emotions involved with infidelity, including betrayal, injury, anger, sadness, grief, disbelief, and related responses and states.

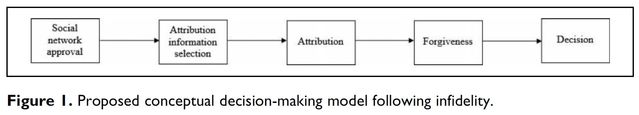

The authors propose a model of decision-making based on prior research in the field of infidelity. It's a detailed model with many nuances, but the framework is straightforward, describing a sequential series of factors leading up to the final decision.

Here's a breakdown of the basics:

1. Social network approval.

Romantic relationships are strongly influenced by social environment — friends, family, institutions, and values, among other things. This applies to all aspects of relationships — attitudes about monogamy, sexuality, including premarital sex, and expectations about the quality and durability of relationships under strain — as well as advice from friends and family about what to do following infidelity. For the purpose of the current study, a key factor determining whether one decides to break up or stay together following infidelity may be social network attitudes (approval or disapproval) about whether couples should try to stay together.

2. Attribution information selection (AIS).

How we pay attention to information is determined by many factors. If we are in favor of something, we tend to look for information which supports that decision, and visa versa. We experience bias as we sort through the information necessary for forming opinions, paying more attention to some kinds of information, and ignoring other potentially important data. In the case of a partner deciding whether to break up after infidelity, when we look back at what happened, our prior conceptions — such as social factors — tend to filter what we notice and how we make sense of the behavior of our partners.

3. Attributions.

After gathering information, people turn to attributions of blame, seeking to determine causality and responsibility. Did he or she do it knowingly, or was it out of his control? Is this a regular thing or a one-time mistake? Could it have been prevented? According to the theory (Fincham & Bradley, 1992), people think about attribution on three dimensions: whether causality lies with the partner or elsewhere (internal versus external); whether the behavior is a consistent pattern, or whether it is an outlier (global or specific); and whether the behavior impacts other areas of the relationship over time or is confined to just one area (stable or unstable). When it is deemed that there is high causality and responsibility, behaviors are seen as internal, global, and stable. In this case, the partner is seen as blameworthy, and the attributions are "conflict-promoting" or "non-benign." When the partner is seen as having low responsibility and causal contribution, behaviors are seen as external, specific, and unstable. In this case, the partner is not seen as blameworthy, and the attributions are referred to as "benign." The nature of the attributions, in turn, predicts the subsequent behavior of the partner who was cheated upon — leading to either stronger negative emotional reactions and greater discord or less intense emotional reactions and greater likelihood of forgiveness and repair. (See this post for more on how people make attributions about blameworthiness.)

4. Forgiveness.

After determining blameworthiness, whether or not to forgive is the next step following a transgression. The presence or absence of forgiveness is crucial to how we relate to someone who has hurt us. When we forgive, our motivation shifts away from negative, destructive responses (e.g., withdrawal, retaliation) toward more constructive responses, including less negative emotion, greater empathy and compassion, and a greater likelihood of repair. It's hard to force forgiveness — the stage has to be set, and even then forgiveness takes work.

5. Decision.

The final outcome to the decision-making process is, of course, making the decision to dissolve the relationship or to stay together. There are many variations on how this decision can take place. One may decide to end the relationship, but have difficulty sticking with the decision and end up getting back together, perhaps only to break up again. Sometimes, painfully, this becomes a repetitive cycle of breaking up and getting back together, often with serial infidelity — which is suggestive of abusive dynamics. One important factor is how certain we are of the decision, regardless of staying or leaving.

The Research

To test whether their hypothetical decision-making sequence fits how people who experience infidelity from their partners actually decide whether to stay or leave, Shrout and Weigel conducted two studies. Both utilized essentially the same format with necessary differences in measures used, looking at a sample of study participants in long-term relationships.

In the first study, participants (about 200 U.S. university students) were asked to contemplate a hypothetical infidelity, starting with assumptions of either social network approval or disapproval. In the second study, participants who had recently learned of a partner's infidelity were recruited to examine their actual decision-making process to see if it matched the sequential model. These participants (115) were recruited from the same university. All had been in romantic relationships in which a partner had cheated on them, and 16 percent were still dating that person. The infidelity had to have occurred within the past three months, to ensure that memories of the decision-making process were clear.

Results

The first study, the hypothetical infidelity situation, found strong statistical support for the sequential model (after controlling for negative emotions, gender, and relationship length). Namely, social network disapproval led partners who had been cheated on to pay more attention to negative information, which in turn increased the chance of finding the partner blameworthy, leading to less forgiveness and greater certainty about breaking up. In addition, they found that women were more likely than men to leave unfaithful partners and were also more likely to make conflict-promoting attributions.

The researchers tested for significance of different orders of the same factors, but did not find a serial mediation relationship, highlighting the relevance of these specific sequential factors in the step-wise process of decision-making.

The second study, whose participants had recently experienced infidelity in a romantic relationship, was designed to determine whether the sequential model carried over into real-world populations. They again found support for the sequential model, noting that those with more disapproving social networks were more likely to make non-benign, conflict-promoting attributions, leading to lower levels of forgiveness and then greater certainty about the decision following infidelity. They noted that greater negative emotion was correlated with certainty about breaking up. As in the first study, they found that alternative sequences of the factors did not reflect the actual decision-making process, again supporting the specific cognitive steps in their model.

Taken together, the results support the theory that advice and attitudes from family and friends change how we pay attention to information in the aftermath of infidelity, which in turn tilts in favor for or against attributing blame, which then influences forgiveness, finally affecting how strongly we feel about the relationship decision.

Further Considerations

These findings are important in understanding how people respond to infidelity, and how we decide what to do in the face of cheating. In addition to supporting what we understand intuitively, this research spells out the cognitive steps involved. Beyond moving the understanding of infidelity further along, having a grasp of the thought process involved in responding to infidelity may be useful for those confronted with the betrayal of trust and injury typical with infidelity.

In general, though it is a less "romantic" way of thinking about relationships, having a rational understanding of the decision-making process can give us more agency and control over how we respond to such events. Recognizing the biasing effect of social approval or disapproval may help us to look at the facts of the situation with greater balance, and understanding how we attribute blame or innocence may help us come to the point of forgiveness when desirable.

It's important when considering the results of this work to note the limitations. For example, the sample of people tended to be young overall, and the studies did not examine demographic variables such as the presence of children, the degree of deep involvement in each other's lives, and similar factors that can make it both hard to end relationships after infidelity as well as hard to stay together with infidelity hanging (unresolved) over the relationship. It would also be interesting to explore situations in which people hide infidelity from friends and families, looking at, for example, the impact of immediate advice as contrasted with long-standing but unspoken family and cultural values and beliefs, or one's own individual values independent of social network influences.

For those with strong motivations to try to keep the relationship together, who want to try to recover, repair, and possibly grow together after infidelity, a close examination of the factors spelled out in this study may assist in the process of dealing with social stigma, blame, and ultimately finding forgiveness — rather than "going through the motions" or "living a lie," while perhaps continuing to harbor negative feelings and missing out on intimacy.

On the other hand, for people who are trying to move away from a relationship after infidelity, understanding the same factors as they relate to confidence about leaving may be equally useful, helping us to feel more settled with an often difficult decision to leave someone we may still love.

Please send questions, topics or themes you'd like me to try and address in future blogs, via my PT bio page.

References

Shrout, M. R. & Weigel, D. J. (2017). "Should I stay or should I go?" Understanding the noninvolved partner's decision-making process following infidelity. Journal of Social Science and Personal Relationships, October 3, 1-21. DOI: 10.1177/0265407517733335

Fincham, F., & Bradbury, T. (1992). Assessing attributions in marriage: The relationship attribution

measure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 457–468. doi:10.1037/

0022-3514.63.4.613