Depression

Depression and a Broken Heart

Heart rate variability gives us clues to the state of our mind and bodies

Posted October 6, 2013

An intriguing link between mind and body can be found by tracking the beats of the heart. People struggling with clinical depression often have an altered heart rhythm compared to people who are not having symptoms. Our pulse should be, at rest, somewhere around 60-80 beats per minute and fairly regular. However, it should not be entirely regular and even, not spot on like the beats of a metronome. The proper and healthy heartbeat has a certain amount of chaotic variation, and it speeds up when you breathe in. Go ahead and lightly press the pulse in your wrist as you inhale and hold the breath, then breathe out and keep your lungs deflated for a bit. As you do this exercise several times, you will notice your heart rate speeds up when you breathe in and slows down when you exhale. This irregularity is called “respiratory sinus arrhythmia,” one sign of a healthy heart and nervous system. It is also called normal heart rate variability, or HRV.

To understand how depression is linked to heart rate variability, let’s start with a short physiology lesson. Our autonomic nervous system (that is, the nervous system that takes care of all the stuff we don’t always actively think about doing, such as breathing, digestion, sweat gland regulation, etc.) is divided into two master sections, the sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and the parasympathetic (“rest and digest”). The parasympathetic nervous system affects heart rate via the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve generally sends a signal to slow the heartbeat and to make that beat more variable. So when you are sleeping or otherwise resting, your heart rate is slower and a bit more chaotic. When you breathe in, the signal from the vagus nerve is suppressed, and your heart rate immediately speeds up.

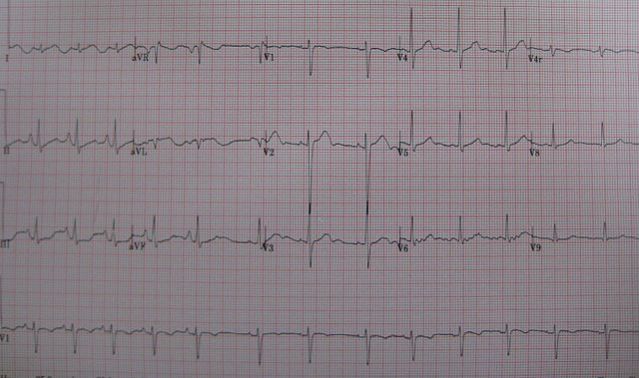

Below is a heart rhythm tracing showing normal respiratory sinus arrhythmia. The heartbeats are quicker at the left side of the tracing and lengthen out (showing a slower rate) toward the middle as the person exhales:

Children typically have high heart rate variability, but as we get older, our HRV tends to decrease. If we exercise regularly, high HRV is preserved, and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and yes, depression all decrease heart rate variability. Why? Well, each of these conditions are states of chronic stress and inflammation in the body. Depressive disorders in particular represents chronic activity of stress hormones, cortisol and adrenaline. These will stimulate the “fight or flight” sympathetic nervous system into action. Since sympathetic action (via the stellate ganglion) is balanced by parasympathetic tone, too much sympathetic activation with chronic stress presumably decreases the parasympathetic signal to the heart, leading to a decrease in HRV. Depression, then, is a state of too much “fight or flight” and not enough “rest and digest.” Decreased parasympathetic tone can be very hard on the heart, not only decreasing HRV but also increasing other types of more dangerous arrhythmias. We may recognize depression by the sad mood, lack of normal interest in activities, sleep difficulty, social withdrawal, and/or suicidal thoughts, but our body also experiences it as a serious dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.

Multiple studies have shown a linear correlation between decreased HRV and increasing severity of depression (1)(2)(3), and this fact may be part of why folks who experience depression after heart attacks have a much worse prognosis than those who don’t get depressed.

All right, well, this news is kinda interesting, but what can we do about it? If our autonomic nervous system is toast from too much stress, trauma, and poor sleep, how to we make it better? Certainly adding healthy exercise as tolerated can help, and regular activity has been shown to increase HRV (4) and decrease depressive symptoms (5). Getting good sleep can also help. Yoga, Tai Chi, and meditative breathing have been shown to increase vagal tone, HRV, and help balance the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems into a more harmonious and healthy relationship (6)(7)(8). Some of my favorite meditation apps are Simply Being and Calm.com.

Over the years I’ve tried a number of different breathing exercises with my patients. Many people can’t tolerate some of the traditional methods I learned (diaphragmatic breathing or body scans) because the focus on breathing can cause anxiety and light-headedness with hyperventilation. There is one method from yoga I like to call “Darth Vader breathing” that seems to avoid the hyperventilation risk and works fairly quickly. And while I wouldn’t practice it standing just behind someone in an elevator, it can be done with a minute or two at your desk or while driving or just before bedtime to help bring your body into a more rest and recovery state to balance out the stressors of daily life.

To do Darth Vader breathing, close your mouth and simply breathe in through your nose and out through your nose at a slow-ish rate. No need to breathe particularly deeply or fill your lungs, just breathe a normal amount. When you exhale, force the air against the back of your palate to make a noise that is like a sigh. Inhales should take 3-4 seconds and exhales about 5-7 seconds. If you close your eyes (if you are driving, please don’t) and do this breathing pattern between 6-10 times, you might find decreased tension in your neck shoulders and a more serene state of mind.

So depression may well break the heart, but with proper recovery and self-care, we can undo some of the ravages of chronic stress and keep ourselves functional and resilient.

Copyright Emily Deans, MD

Special thanks to Grayson Wheatley, MD, for his guidance in researching this article.