Fear

Can of Worms? Pandora’s Box? Divulging Your Dark Secrets

Unpleasant, yes, but certain things need to be brought up. Others shouldn’t.

Posted December 1, 2016

As a psychologist, over the years I’ve seen clients show tremendous ambivalence about bringing up certain topics. Such anxiety-filled reluctance is particularly common when subjects relate to unresolved feelings of fear, trepidation, guilt and shame. Ironically, their resistance to prying open what they regard (and sometimes label) a “can of worms” is a cue that the matter, if it’s to be remedied, may be crucial to discuss. Otherwise, their professed therapeutic goals may be unattainable.

Beyond a professional setting (where therapists are specifically trained to facilitate this “sharing of the unsharable”), clients’ cultivating the courage to open what they perceive as a can of slimy, squiggly worms can feel even more daunting. For once those oozy invertebrates are out of the can, they may be impossible to get back in.

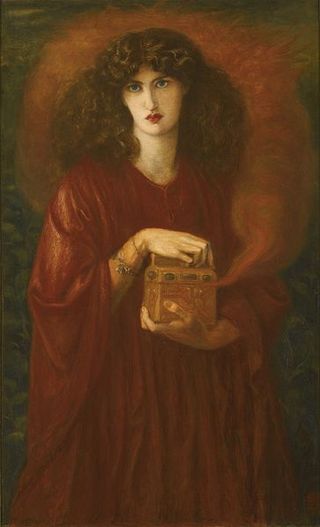

You might well ponder: “How is opening a can of worms different from lifting the lid off Pandora’s Box?” Can these two precarious, or perilous, acts be meaningfully distinguished?

The rest of this post will attempt to explain why it’s essential to make the distinction. You certainly don’t want to tempt the fates by opening Pandora’s Box (originally, before an early mistranslation, known in Greek mythology as a jar). For when, out of irresistible curiosity, Pandora did open the top—despite being told, under any circumstances, not to—she unwittingly let loose all evil into the world. And tragically, once out, this bottomless pit of ugliness, hate, misfortune, suffering and death could never again be contained.

Though in far less dramatic (or fatal!) fashion, the adverse connotations linked to figuratively opening a can of worms are similar. That is, to let loose worms initially contained in a can (so, as that expression originated, a fisherman could have live bait to better lure fish to his hook) was to risk the possibility of never being able to maneuver them all back in the can again.

In both metaphors we have the notion of a “break-out,” making things infinitely more complicated and challenging than would have been the case otherwise. As characterized on one website, opening a can of worms means “to attempt to solve one problem, or to do something, that creates a whole litany of other problems that were not there in the first place” (todayifoundout.com). You might compare this aggravating state of affairs to the expression, or directive, to “let sleeping dogs lie,” which The Free Dictionary denotes as: “Do not instigate trouble; leave something alone if it might cause trouble.”

Nonetheless, there’s a key difference between, on the one hand, opening a mortally threatening Pandora’s Box and, on the other, opening a can of worms. For, in essence, the latter expression really pertains much less to worms (which are themselves quite harmless) but to the fear that addressing anything tricky or challenging could make matters worse (maybe much worse). Returning to my therapy clients, when they employed this cautionary expression they weren’t referring to the sensitive subject they’d been avoiding as inherently scary, but rather their all-too-personal apprehension about the possible repercussions of bringing it up. As in, “What if that sleeping dog has rabies and my waking him up could make him bite me?!”

What I regularly tell clients with such fears is that if they’re not yet ready to bring something up, then—by all means—don’t. But I also assure them that chances are that when they’re ready to disclose their zealously guarded secret, they’ll likely discover they’re actually not opening a can of worms at all (and certainly not some evil-saturated Pandora’s Box!). That is, I let them know that their willingness to divulge something which up till now has felt too dangerous to go public with, will probably defuse it. That the toxic energy so long attached to it will probably be released—at long last, discharged.

Almost invariably, when clients do evolve the mental and emotional strength to share the narrative of that which has saddled them with exaggerated feelings of anxiety, sorrow, guilt, or shame, the residual negative impact of that situation is greatly reduced. For they can then be helped to understand what they did—or what happened to them—in a new, more realistic, and substantially more favorable light. And once that event (or series of events) has been freshly illuminated, its wounding to their sense of self can begin to heal. Now they can recognize how their original, negatively distorted interpretation of what transpired seriously compromised their self-image.

To give two simple examples: If they were molested as a child, they may have come to see this grave boundary violation as saying something bad not just about the perpetrator but about themselves, too—and likely, their body as well. Or, if they accidentally or impulsively harmed someone, they may have been so shamed for doing so that they came to see themselves as worthless, undeserving of any good fortune. And they may even have been told this by punitive, authoritarian parents. Consequently, my helping them begin to “own”—from both their head and heart—the authority they originally felt compelled to forfeit to their elders can be enormously beneficial to their healthy development.

Moreover, if a client’s parent (or perhaps older sibling, or other relative) is still living and, from the client’s characterizations, I’m fairly confident that this family member is “reachable” (i.e., not overly defensive or personality-disordered), I’ll recommend a joint consultative session. That way my client can share (hopefully, with meticulously-timed, mediating interventions on my part!) what, at great psychological costs, they’ve so long held in. I’ve almost always found such deeply intimate sessions not only to be a most healing experience for the client, but for the other individual(s) involved as well.

In the real world, of course, what ideally needs to happen can’t easily take place in a therapist’s office. So let me suggest how it could happen outside this traditionally protected setting. The question is how, on your own, you might engender a “safe space,” whether at home or in some public locale, to share what might be truly helpful for you to disclose—without, that is, opening a much-feared “can of worms.”

It’s only natural to be concerned about bringing up something that could hurt, offend, or even enrage another—and so put the entire bond (such as it is) at risk. Yet if that relationship has the ability to grow, so that it might attain a more satisfying level of sharing and emotional closeness—or, if old psychic pains are to be addressed and, at last, soothed or allayed—such confrontation may be imperative.

If nothing else, if you’re ever to learn how much unrealized potential the relationship might have, there may be no viable alternative other than (gingerly!) approaching the other person about what's cause the tension, or rift, between you. For unless the relationship’s limits can be put to the test, how else can you find out whether it’s worth any further pursuing? And it’s possible that, given the additional maturity and experience both of you have accumulated since its weakening, or “rupture,” you might discover that it has more room for growth and mutual nurturance than you imagined: That the worms you so feared might turn into lethal snakes were, after all, just “gummy worms”—slippery, but kind of tangy, maybe even sweet, as well (!).

If, on the contrary, you allow your fears to govern your behavior and don’t risk bringing up what you’ve never made peace with, your continuing to “play it safe” virtually guarantees that the relationship—assuming you don’t decide to let go of it altogether—will remain superficial and frustrating. Never really “tried,” there’s no hope it will ever progress into anything more gratifying, more fulfilling, than it’s been up till now.

But (as I’ve already indicated) if, finally, you’re willing to risk communicating what you’ve long shied away from, it must be done with painstaking care and discretion. For broaching such delicate topics requires consummate tact, restraint, and diplomacy.

Before even determining whether to engage the other person with the issue that’s been stuck in your craw, you need to honestly ask yourself: “Is my motive here to blame, castigate, humiliate, or shame this person? to get them to feel as bad about themselves as they once made me? Or is it to see whether I can enable them to understand just how their past behavior hurt or antagonized me—and to do so in a way least likely to provoke them, or arouse their defenses?

If the latter, fine, definitely give yourself permission to address your past upset(s) with them. But if the former, realize that though you might need to—or, frankly, even enjoy—venting your grievances, to approach them aggressively (vs. assertively) is hardly likely to do anything other than further aggravate the situation, or increase the distance already existing between the two of you.

Obviously, if you’re emotionally prepared to put the relationship behind you—even if it’s with a close family member—you might want to “go for it” in any case. But if you’d rather avoid opening a, well, Pandora’s Box, you’ll want to summon up your most gracious, most understanding, forgiving, self—and then explain the grudge, or “unfinished business,” you still have with them.

NOTE 1: Here are some complementary posts of mine that, in more detail, describe the dynamics of broaching difficult subjects with others, and how best to give—and receive—criticism (particularly as relates to your partner):

“Criticism vs. Feedback—Which One Wins, Hands Down?” (Parts 1 & 2)

“Want to Avoid Blow-Ups With Your Partner? Here’s How”

“How to Confront Others to Confront Themselves”

“Why Criticism Is So Hard to Take” (Parts 1 & 2)

“4 Essential Rules for Approaching Couples Conflict”

“How to Talk About the Things You Don’t Want to Talk About”

“Courage in Relationships: Conquering Vulnerability and Fear”

“How to Respond When Your Partner’s Bark Feels Like A Bite”

NOTE 2: If you could relate to this post and think others you know might also, kindly consider forwarding them its link.

NOTE 3: To check out other posts I’ve done for Psychology Today online—on a broad variety of psychological topics—click here.

© 2016 Leon F. Seltzer, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved.

---To be notified whenever I post something new, I invite readers to join me on Facebook—as well as on Twitter where, additionally, you can follow my various psychological and philosophical musings.