Stress

What Is Pandemic Fatigue and What Can You Do About It?

How to understand the psychological impacts of burnout as COVID presses on.

Posted February 3, 2021

Six months ago, when I asked my clients how they were feeling, typical responses included “stressed,” “worried,” and “lonely.”

Today, when I pose the same question, I get very different answers. The consensus, from CEOs to the newest hires, seems to be: “exhausted,” “burnt out,” and “depleted.”

What initially seemed like a hiccup and a handful of short-lived but manageable disruptions to our normal lives instead became a global pandemic. For 11 months, we have worked and studied online, remained at home or in social bubbles, and have become Zoom, mask-wearing, disinfecting, social-distancing experts. We have weathered the pandemic without our normal routines, support systems, or coping mechanisms.

It seems endless. And we are collectively exhausted.

As the pandemic presses on, many of us feel like we have nothing left to give and are increasingly unable to navigate the stress of the pandemic.

When stress is good

Our body has a wonderful internal system in place to deal with stress. It's called our security motivation system, and it protects us by recognizing when a threat is present in our environment, elevates our attention to address it, and points us in the direction of safety.

This is super helpful in situations where a threat is short-lived. When someone slams on their brakes, stumbles towards us in a bar, or raises their voice in anger, it’s helpful that our body tells us to protect ourselves. In the short-term, stress gives us the boost of energy we need to solve or escape a problem.

Understanding chronic stress

When stress continues over time, however, it has a wholly different effect, both physically and emotionally.

Chronic stress is any situation or experience that occurs over a period of time, which overwhelms our ability to cope. (In contrast to acute stress, which is a discrete stressful event, such as a car accident or physical attack.)

Chronic stress, which demands elevated levels of energy and cognitive hypervigilance, cannot be sustained over time and in the long-term is extremely harmful to our health.

The stages of stress

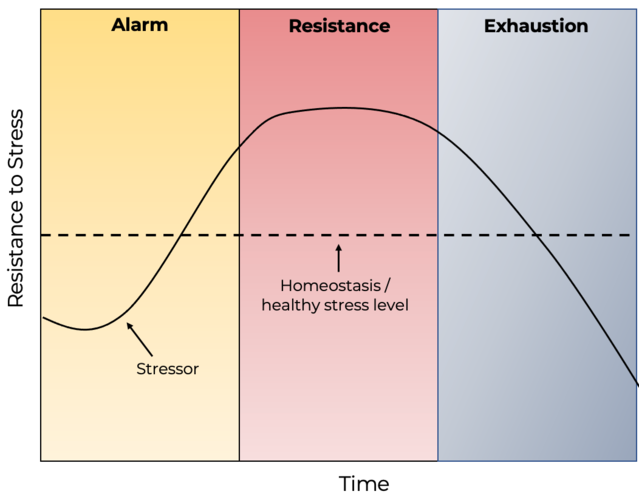

Our bodies deal with stress via a process called General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), which aims to cope with stress and return us to normal, healthy levels of functioning. GAS consists of three stages:

- Alarm stage. When we encounter a threat, our bodies protect us with a combination of physical and emotional responses. We enter the alarm reaction stage, where chemicals like cortisol and adrenaline activate our fight-or-flight response.

- Resistance stage. In the next stage, the resistance stage, our bodies remain on alert, but start to heal and repair themselves. As the shock of whatever threat we have encountered diminishes, our blood pressure, adrenaline, and cortisol begin to normalize. If our stress is not resolved and the threat is ongoing, however, we stay activated in a heightened state of alert and continue to release cortisol and other stress hormones.

- Exhaustion stage. When we remain in a state of hypervigilance for too long, our minds and bodies eventually exhaust their capacity to cope with stress. This is called the exhaustion stage. If we reach this stage, our ability to deal with stress diminishes and we may begin to experience a variety of emotional, cognitive, and physical effects, including:

Emotional

- irritability or frustration

- depression

- anxiety

- feelings of hopelessness

- feelings of defeat

Cognitive

- easily distracted

- trouble concentrating

- lack of interest in activities

Physical

- fatigue

- body aches

- compromised immune system

- difficulty sleeping

What we can do

As infections and death tolls rise and new variants emerge, we may feel frustrated by the interminability of COVID-19, the endless cycle of bad news, or get down on ourselves for not adjusting “better” to our new reality.

Perhaps the first thing we need to work towards is developing greater compassion for ourselves and empathy for others. COVID has stripped our lives of normalcy, support systems, and things that bring us comfort and joy. It is hugely difficult, and simply getting from one day to the next can be a huge accomplishment.

We can’t stop the pandemic (yet), but we can cope with the stress it puts us under in healthy ways.

Here are some tips to manage pandemic fatigue, both individually and in your organization.

At home:

- Make time to consciously rest, repair, and recover. Put a self-care plan in place with things you love.

- Exercise. Any movement is good, whether it’s a HIIT workout or a walk around the block.

- Go outside. Being in nature is one of the best things you can do for your mental health and wellbeing.

- Practice meditation, mindfulness, or deep-breathing.

- Talk to people you trust about how you feel, join a support group, or consider psychotherapy.

At work:

- Set up a wellbeing network and dedicated resources to support employee mental health.

- Train your workforce in mental health awareness, wellbeing practices, resilience, and emotional intelligence.

- Host information sessions with experts on the ongoing stress of the pandemic and coping mechanisms.

- Overdo it on team-building activities and opportunities for employees to connect (virtually).

- Consider your messaging on mental health and wellbeing and what resources are available to employees.

References

Woody, E. Z., & Szechtman, H. (2011). Adaptation to potential threat: the evolution, neurobiology, and psychopathology of the security motivation system. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 35(4), 1019–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.08.003

Zuck, Michael; Frey, Rebecca "General Adaptation Syndrome ." Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, 3rd ed.. . Retrieved January 12, 2021 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcript…

American Psychological Association. (2021, February 2). APA: U. S. Adults Report Highest Stress Level Since Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic [Press release]. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2021/02/adults-stress-pandemic