Personality

Personality in the Time of COVID

Are we truly being ourselves by ourselves?

Posted April 23, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

When the virus came to our shores, I knew much would change, but I was fairly certain that at least one thing would be minimally impacted: my online course in self-assessment. In this course, students engage in a multitude of tasks aimed at introducing them to various theories and methods of studying personality. It is largely self-guided and task-oriented, and thus easily done on one’s own time, in and around the rest of life. So it was unsurprising that as I and my students in my in-person courses struggled to adjust to moving fully online, the already-online course was moving along rather well in the first two weeks of the shutdown. However, the third week brought with it an unanticipated wrinkle.

In that week's unit, students learn about intra-individual behavioral variability: This is the extent to which we adapt to different situations in unique ways, such that our behavior is inconsistent across situations (yet predictable given some knowledge of the person and the situation). For example, sometimes I talk a lot, and sometimes I don’t. Knowing whether I’m teaching a class, in a meeting, or in an elevator with strangers will be helpful in predicting how much talking I’ll do (a lot, some, and not at all, respectively). When I’m asked if I’m a talkative person, I’m averaging across normal situations I encounter to provide a general summary. Our generalized behavior makes up part of personality traits, but some theorists (correctly, in my opinion) argue that broad trait descriptors overly simplify our personalities.

Thus, I ask my students to keep two types of diaries in Unit 6. The first is a 5-day behavioral diary, in which they simply think back at the end of the day on a list of 50 behaviors (10 behaviors for each of the Big Five personality traits) and indicate whether they engaged in that behavior (e.g., talked a lot, hugged someone, felt sad, read poetry, finished a task on time, etc.). The second is a situational diary, in which I name a few specific times in the past week (e.g., Tuesday at 10:30 a.m., Saturday at 8:00 p.m.) and ask them to describe where they were and what was happening. They then score these situations in terms of categories called the Situational 8 (DIAMONDS; Rauthmann et al., 2014), each of which can be considered a feature of a situation. For example, the category “Adversity” asks to what extent someone was threatened in a given situation.

Normally, this is a fairly straightforward process, but I began to suspect that the pandemic might complicate the matter. Specifically, it seems that people feel hemmed in by what’s happening right now. I know my days feel eerily similar to one another, and I thought this might result in some limited variation in my students’ daily behaviors and the situations they were encountering as well.

Some psychologists would refer to quarantining as an extremely “strong” situation—that is, our behaviors are likely being driven by external forces (situations) more than internal forces (personality). In a strong situation, it could be argued that one is not “being” her or himself. So, I had some questions: How much has life changed in quarantine? Do we do the same things every day? Do we keep seeing the same circumstances over and over? Are we being ourselves during this time?

Those who know me know that I like to answer questions with data, and the current situation has not managed to restrict this proclivity! The following is a set of analyses of student work from both normal periods of time (about 20 people completed this work) and the current situation (about 15 people). Thanks to all students who allowed their data to be used for these analyses.

Do We Do the Same Things?

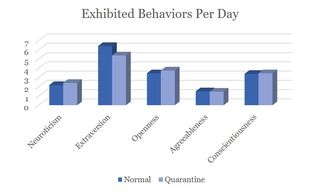

To answer the first question, I examined daily reports of specific behaviors, aggregated into behavioral categories matching the Big Five personality traits. The figure below presents the average number of category-relevant behaviors per day (max = 10) for people in normal circumstances (darker blue) and in our current circumstances (lighter blue).

The initial takeaway here would be that life looks… pretty similar? The largest difference is average levels of behavior falls in the Extraversion category, and it conforms to expectations, as some of the extraversion-relevant behaviors (i.e., mixed well at a social function, went out to socialize, chatted with strangers, introduced myself to someone new) seem much less likely in our current situation.

Do We Encounter the Same Situations?

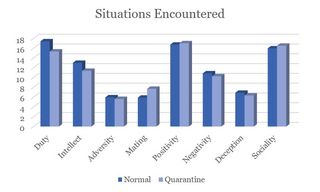

Another way to consider how much life has changed is in terms of the psychological situations that one encounters. Do we find ourselves in similar circumstances? Again, obviously not. But in terms of general psychological situations (the way we construe the features of our current circumstances)?

I would take time to explain what each of these categories meant, but the real story is again the level of similarity across the two circumstances. Unsurprisingly, we do see more situations that call for something to be done (Duty) or for deep processing of information (Intellect) in normal times. And before we get overly excited about the uptick in the Mating category, I should note that some of the items marking that category involve the mere presence of a romantic partner. It was also interesting that there wasn’t a marked increase (and actually a slight decrease) in Negativity in quarantine. In all, however, I would argue once again that these two periods are marked more by similarity than differences.

Is Each Day Just Like the Previous One?

So far, we’ve established that we might do similar things and encounter similar situations, but what about the monotony? Lately, people seem to feel that each day is remarkably similar to the previous, as evidenced in numerous memes regarding confusion as to the current date. I know I describe my life this way to the few others who inquire. But has this been the case with my students?

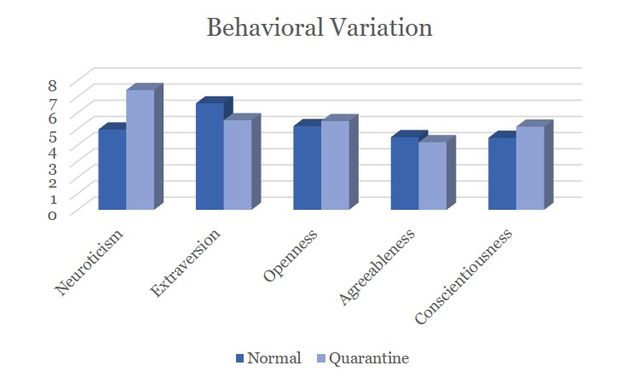

To determine whether our days vary less than they used to, I computed an average behavior (or situational) level for each person, then summed the absolute value of the differences across days. If that doesn’t make sense, I just performed some (rudimentary) nerd magic to quantify how much our days differ from one another. Here are the data for behavioral variability:

What we see is greater within-person fluctuation in Neuroticism from day to day. Don’t I know it?! If you feel like some days you’re filled with dread and others are calmer, you’re not alone. Other categories are again rather similar. But do we keep encountering the same situations?

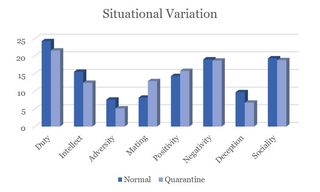

Maybe no more than we usually do. Most of the differences here are fairly small (you’ll have to trust my statistical instincts on this one) save for mating opportunities, which are both more abundant (as evidenced in the previous relevant figure) and more variable (as evidenced here). In other words, at least for this group of people, psychological situations change as much from day to day now as they did before the pandemic. Perhaps this highlights the difference between a physical situation (temperature, lighting, number of others present, etc.) and psychological situation (What is possible in this circumstance? What does the circumstance ask of me?).

Are We Being Ourselves?

None of the previous data speak directly to an important question: Are you still you right now? During our recent struggles, I have found myself thinking about what I value, the things I’ve let slide and the things that continue unabated, what I might be learning about myself, and what might change about what I do when this is all over. In fact, the primary impetus for this blog post was actually a student’s commentary on our current situation as it applied to our coursework: Essentially, they felt they had discovered something about their nature that was previously unknown to them (in this case it was that they might be more extraverted than they had previously thought—something I imagine others are certainly considering, at least temporarily). Whether or not we are being ourselves is an incredibly thorny question, and I’m going to address it in a way that is woefully short of its heft but makes use of what I have at my disposal.

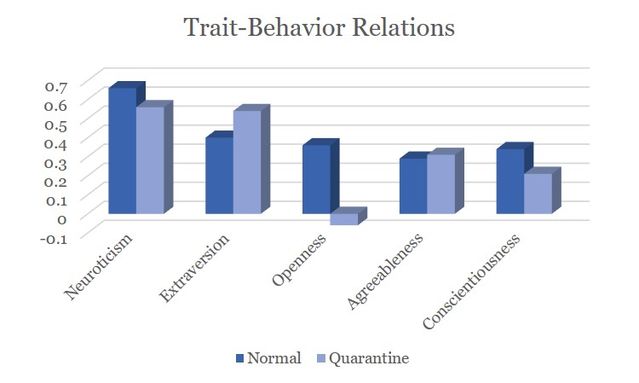

To determine whether we are behaving as ourselves in this time, I compared concordance rates between people’s general self-evaluations (e.g., how extraverted am I, generally speaking?) and their aggregated relevant behavior in quarantine. The figure below plots the correlations between traits and their behavioral manifestations across both time periods:

Again, what one might expect here is that the darker blue bars would be higher—indicating a stronger connection between our sense of self and our actions in “normal” circumstances. And we do see that for Openness to Experience (e.g., trying new things, reading about other countries, thinking about our emotions, discussing politics, reading books and poetry, enjoying art), indicating that despite the well-publicized forays into breadmaking and other new hobbies, our time in isolation may be (understandably) restricting the expansion of our horizons—at least for those who want them expanded in general. Conversely, it is possible that people who are not normally open to trying new things are doing so more often, and others are simply maintaining their normal tendencies, which could also generate this pattern of results.

We also see this dampening effect of quarantine to some extent for congruence in Conscientiousness-related behavior (often tied to work or duty), which makes some sense, given the change in our work and school situations. However, the general pattern is again one of similarity more than stark contrast—only the Openness difference strikes me as noteworthy. Further, Extraversion-related behaviors seem more in line with our general sense of self during quarantine, which might parallel some of the findings from studies on online versus offline behavior in suggesting that new circumstances can sometimes lead to us being more ourselves, instead of different selves (Gosling, Augustine, Vazire, Holtzman, and Gaddis, 2011).

In Sum

The truth is that these are just a few data points that are not representative of the population at large. I will not be publishing these data in a scientific outlet due to many, many flaws, perhaps the least of which is the small, specialized sample—we can quibble endlessly about the fidelity of the measures, sampling strategy, importance of the categories chosen, etc. Furthermore, the intent of this post is not to minimize the psychological toll that this is taking on all of us—even those fortunate enough not to be directly touched by the frightening implications of the disease itself. It is tremendous, and these times are difficult.

That said, I do hope that this can make it seem possible that we are still ourselves, even now, in small but fundamental ways—and that if you’re looking for normalcy, perhaps it was inside of you all along.

References

Gosling, S. D., Augustine, A. A., Vazire, S., Holtzman, N., & Gaddis, S. (2011). Manifestations of personality in online social networks: Self-reported Facebook-related behaviors and observable profile information. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(9), 483–488. https://doi-org.uscupstate.idm.oclc.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0087

Rauthmann, J. F., Gallardo-Pujol, D., Guillaume, E. M., Todd, E., Nave, C. S., Sherman, R. A., Ziegler, M., Jones, A. B., & Funder, D. C. (2014). The Situational Eight DIAMONDS: A taxonomy of major dimensions of situation characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), 677–718. https://doi-org.uscupstate.idm.oclc.org/10.1037/a0037250.supp (Supplemental)