Resilience

Do Your Kids Suffer From "Halloween Fragility Syndrome"?

Why sheltering youth from danger is disastrous for their mental health.

Posted November 1, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Amid growing fears around "offensive" costumes and a so-called "cancel culture" taking hold of North America, "Halloween Fragility Syndrome" hit new heights on October 31, 2019, when the City of Montreal officially canceled trick-or-treating for what turned out to be light rain.

"Halloween Fragility Syndrome" is not really a thing. As an evolutionary anthropologist and professor of psychiatry who works on cultural dimensions of mental health, I coined the phrase ironically to describe growing hypersensitivity around an old ritual that used to permit—and celebrate—transgressive behavior among young people.

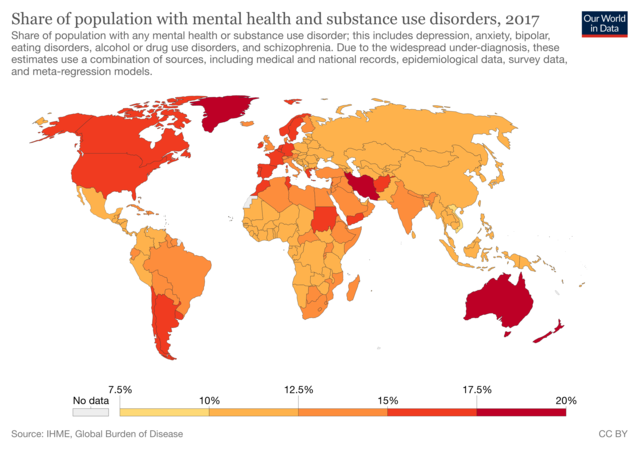

While my home city of Montreal did not exactly police costume etiquette, the official decision to cancel festivities because of unpleasant weather was consistent with a broader culture of over-protection and aversion to the "uncomfortable"—a growing trend in parenting, teaching, policy-making, and clinical guidelines—that psychologist Jonathan Haidt has termed "safetysim." There is a growing consensus among social and cognitive scientists that the mental health consequences of safety are disastrous. For the psychologist, Jean Twenge, safety culture and increased sheltering from real, face-to-face life on social media are largely to blame for the skyrocketing rates of mental illness and the “epidemic of anguish” among our youth. Oddly, this trend appears to be inversely correlated with human and economic development. Epidemics of mental illness, thus, are much more prevalent in high-income countries, with anxiety disorders, depression, and substance use disorders topping the charts.

Where have we gone wrong?

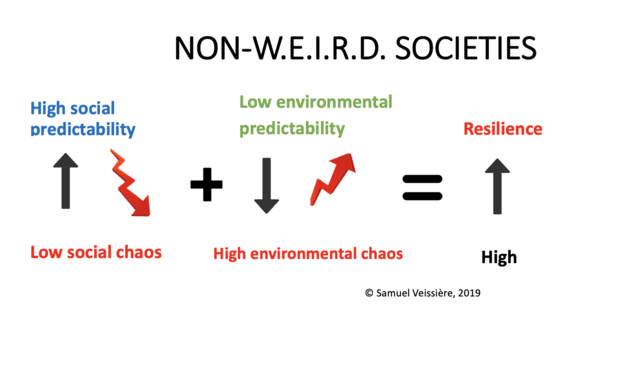

A brief anthropological look at contexts where rates of distress appear to be lower may help shed light on this conundrum. Readers familiar with large cities in low-income countries with strong traditional cultures (think of places in Manilla, New Delhi, Karachi, Lagos, or Johannesburg) may have noticed an interesting paradox: For most western people, these environments will seem unbearably chaotic. All these cities are plagued with chaotic traffic and dangerous roads, unbearable noise and pollution levels, high crime rates, and in many cases, higher vulnerability to natural disasters. Getting from A to B can take forever in such places, or turn out to be impossible. Yet, the majority of people who grow up, live, work, and go about their daily life in these environments, appear much more composed, flexible, and resilient in the face of disorder than their W.E.I.R.D. (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic) counterparts.

Is high-chaos a necessity for human resilience?

Our species did evolve, after all, in highly dangerous, unpredictable, and volatile environmental conditions. It does seem plausible, then, that our basic emotions and cognitive architecture would have evolved to be attentive to dangers—and perhaps to require chaos in order to develop fully. In this view, a minimal amount of danger may be necessary in early developmental phases to rehearse optimal functioning strategies in the real world.

While this evolutionary view is partly correct, current neuroscience also tells us that the human brain’s main function is to predict and guide action from picking up on patterns of statistical regularities in the world. The human brain, truth be told, is deeply averse to chaos, and seeks to produce order and predictability even where there is none. To better understand resilience in the face of ostensible chaos, we need to review one more ingredient in the lives of most non-WEIRD peoples. This ingredient is what I call "traditional culture." In evolutionary terms, we also need to understand that our species' success in the face of chaos was only made possible by making the world predictable together, through the cultural norms, beliefs, values, and toolkits without which no individual could exist or survive.

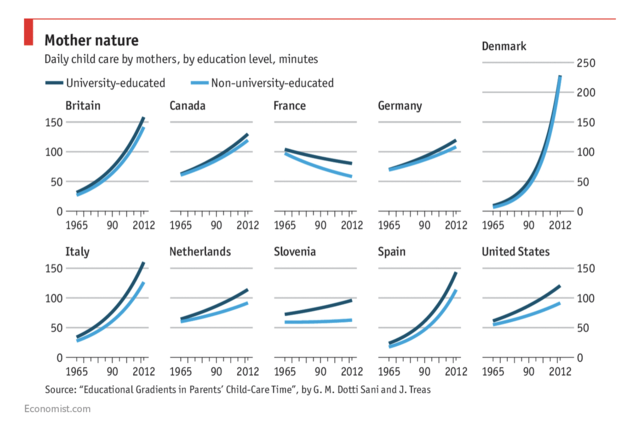

While the "outside" world non-WEIRD people live is highly unpredictable, their social world remains paved with many more recognizable bearings. Extended families, castes, tribes, clans, and religious activity provide a strong buffer of social support, in addition to frequent opportunities for community gathering and bonding through ritual worship and family customs. In traditional cultures, the paths of people’s life "choices" (in terms of what job to pursue, where to live, whom and when to marry, how to be desirable and good persons, etc.) are usually paved out for them, in a world more or less ready to integrate as it is. In the West, conversely, the demise of family structures, religion, and large systems of belief, along with rising individualistic values and higher purchasing power have placed an enormous burden on increasingly younger individuals to reinvent their lives and become personally responsible for finding everything from their dreams and goals to "meaning" and ideal partners.

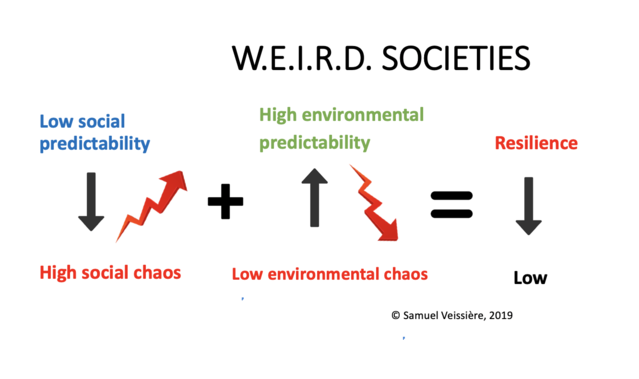

The "outside" world for WEIRD peoples, however, is highly predictable. In the West, crime rates and traffic accidents are at a historic low, public infrastructure can respond and recover optimally from natural disasters, and all domains of civic and commercial life have become hyper-regulated. Yet, a strange trend summarized as “Crime Down, Fear Up” has been identified in America. In the Western World, children now spend up to 50 percent less time unsupervised compared to 50 years ago—when our social worlds were still much more predictable and were actually unsafe.

This brief discussion may enable us to sketch a tentative recipe for the relationship between predictability and human resilience.

First, social predictability appears to be a more important protective factor against mental illness than environmental predictability. Second, some amount of environmental unpredictability (as long as it is buffered by a protective social world) may also help with resilience. While environmental predictability alone is either insufficient for resilience, too much predictability may be risk factor for low resilience.

What can W.E.I.R.D. Societies do?

Making our environments more dangerous would be a strange insult to the centuries of medical, infrastructural, economic, and political progress than enabled us to live longer, safer lives. Surely, many lives in non-W.E.I.R.D. societies still stand to benefit from such progress. Our cultural progress, however, might have taken strange turns and ventured too far from the kinds of communal, ritual, and spiritual lives that characterized the human experience for most of our species’ history.

Until recently, most cultures encouraged their youth to undergo difficult rites of passages that would teach them to discover new things and learn to fend for themselves in the world. The Australian rite of walkabout among aborigines provided such an opportunity; as did the culture on going a “Grand Tour” of Europe on horseback among the British elite of the 17th Century—a rite later extended to a Voyage to the Orient in the Victorian period. In Australia, Western Europe, and other parts of the W.E.I.R.D. world, some youth take a Gap Year to go and see the world before or after university. In their recommendations for fixing safety culture, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff are strong advocates of the Gap Year as an important lesson in real-world unpredictability and ambiguity. For those who may not be able to afford such a trip, getting a working-class job can offer other important lessons in flexibility—like learning to work and live with people whose lives and values are different from our own.

For Haidt and Lukianoff, undergoing military service can offer the most antifragile of such experiences. By serving in the military, youth learn to toughen up in new environments, can become attentive and empathetic to the problems faced by other people, and can foster strong bonds of solidarity with fellow soldiers from different walks of like. In Israel, for example, the majority of youth serve two to three years in the military, after which many of them go on to travel the world for one or two more years—often in "dangerous," remote places. By their mid to late twenties, many Israelis have reached levels of maturity, real-world knowledge, resilience, and resourcefulness that are becoming increasingly rare in the rest of the West.

Before such rites of passages can be restored in greater numbers, an easy step to take with our young ones is to let them learn to take measured risks unsupervised. Parents who are hesitant or unsure how to start will find useful tips and local groups through the Free-Range Kids community. Halloween evening, in any case—rain or snow, hail or storm—is a perfect moment to let your kids venture out in the dark!