Fantasies

Now They Tell Me: Yes, Fiction Writing Is Hard!

Shifting from nonfiction to fiction pushes my thinking in new ways.

Posted June 9, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- The border between fiction and nonfiction writing is wider than I expected.

- Fiction isn't "lying"; it's using my imagination.

- In fiction, emotion trumps data. That's hard for an academic researcher sometimes!

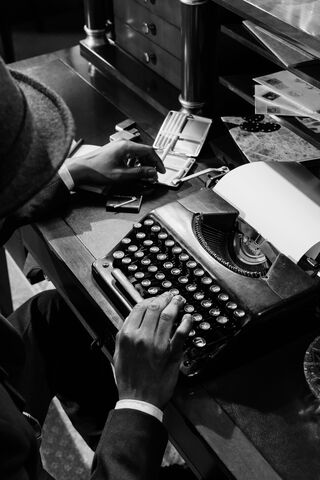

Having written nonfiction for three decades, I’m crossing borders by trying to write fiction. It’s not been an easy go. Part of the struggle is that I fear my head overshadows my heart.

Most of my writing life has focused on presenting data and arguments that address some fascinating scholarly question, like is organizational strategy linked to human resource management? How do transition economies change over time? What organizational patterns of creativity exist, if any? Why do so many organizational acquisitions go wrong?

Please don’t yawn.

To address these questions, I spent time reading, crunching numbers, and interviewing people. My writing “style,” such as it was, involved describing the research process and results in dry, straightforward prose and hoping no one fell asleep. Emotions played no role on the page.

As time passed, though, I noticed some scientists and scholars stepping beyond the jargon-filled academic journal sphere to offer dramatically more interesting ways to tell their research stories. An early PBS series, COSMOS, blazed the trail. Astronomer Carl Sagan likely reached millions of people as he told the stories of the universe. I never read any of his journal articles, but I couldn’t get enough of the show.

Eventually, business and science researchers became better at “telling stories” to make their points. Books like Houston, We Have a Narrative (Randy Olson) helped scientists develop better stories for presentations and articles. Win Bigly (Scott Adams) focused on the power of persuasion, and even Antonin Scalia and Bryan Garner showed how to write better legal cases in Making Your Case.

I charged in.

I studied, went to workshops, and took online courses on what’s called creative nonfiction, which is using techniques from fiction to write about events, people, or research. For me, Tracy Kidder’s The Soul of the New Machine was an eye-opener in the way he turned what could have been a boring story—the development of a computer—into a page-turner.

Along the way, I began using creative nonfiction in my academic work. But, always, I had clear sources and references for the analysis that I tried to make more interesting to read.

So, moving to fiction should have been a natural next step. No such luck. When I first took an online course in writing fiction, I gave up, in anxious frustration.

“I’m not a good liar,” I whined to my classmates. “I need something real—some evidence, references, a source to quote or draw from.”

They tried to coach me.

“It’s not lying,” said one. “It’s using your imagination.”

“You’re not telling a fib, but, rather, you’re making it more interesting as a story,” said another.

“Get over needing hard data. Show what the character feels, what’s in her head, what’s in her heart,” said the most insistent one.

Now, as a fiction-writer-in-training, I feel that I’m floating on an iceberg, adrift. My analytical self wants something concrete “to write from” as I pen mysteries…something that I’ve studied, analyzed, torn apart, and put back together.

My fiction-writing colleagues shake me by the shoulders and say that no one really cares about the data. Readers care about the person who wrestles with some challenge, whether it’s other people or themselves. It’s the heart, the inner life of the character, that really grabs attention—not the facts.

I understand what they’re saying. My head sees it, gets it, and desperately wants to make it part of me. I’m not there, but I want to be. Step by step. Wish me luck.