Neuroscience

A Brief History of Neuroscience

How we came to understand the biology that shapes our behavior.

Posted December 18, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer Ph.D.

Key points

- Neurology has a long history, but the brain was not seen as important by many ancient civilizations.

- The invention of the microscope and chemical staining developed by Golgi gave rise to modern neuroscience.

- Many anatomists believed in the reticular theory, seeing the nervous system as a single and unbroken network.

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal found evidence for the neuron doctrine, showing that the nervous system contains cells.

Neurobiology profoundly influences our lives, impacting our health, thoughts, emotions, and behaviours (see How Our Neurobiology Shapes Our Daily Lives; Pang, 2023). Despite its importance, our scientific understanding of our nervous system only emerged recently, after many twists and turns, new inventions, and bitter rivalries. Here is a brief history of neuroscience.

Early concepts

Ancient Egyptian physicians already knew that injury to the spinal cord can result in paralysis and that brain lesions can impact speech functions (van Middendorp et al., 2010; Pang, 2023). Despite these insights, they valued the heart as the seat of the soul and did not see the brain as important, even discarding it during mummification (Guenot, 2022). Other ancient civilizations, like those in Mesopotamia and China, similarly did not place much emphasis on the brain or the nervous system (see Ancient Concepts of the Mind, Brain (and Soul); Pang, 2023).

Anatomical descriptions of the nervous system can be found in many texts from antiquity to early modern times. Bendetti likened it to “the roots and fibres of a tree” in 1497 and some early anatomists understood that this network could carry sensory information (Walsh, 2017). Some also noted that it can send signals outwards, with René Descartes imagining animal spirits—called pneuma—flowing through hollow nerves to inflate muscles like a hydraulic fluid (Ehrlich, 2022). Hydromechanics flourished during Descartes' lifetime—one of the many topics he studied (Gregory, 2017)—and was extensively used in the lavish fountains of the period and as a power source for early machines. This metaphorical comparison to the latest technological advancement continued for centuries: German anatomist Otto Deiters compared the nervous system to a railway network and Hermann von Helmholtz and Emil du Bois-Reymond likened it to a telegraph system (Ehrlich, 2022). This conceptual information exchange with engineering was not just one sided: The growing understanding of neurology inspired telegraph engineers like Samuel Morse—who invented the Morse code—and Werner von Siemens—who founded the German company named after him—to model telegraph networks after the nervous system, with great success (Ehrlich, 2022).

Microscopic revolution

Two key inventions revolutionised our understanding of the nervous system: The microscope and chemical staining.

The term "microscope" was coined by the German doctor to the pope Johannes Faber—who was known in Italy as Giovanni Faber—in 1625 to describe an instrument Galileo invented in 1609 (Wollman et al., 2015). Although lenses existed for a long time, it was a family of Dutch spectacle makers who created the first microscope in around 1590 (Wollman et al., 2015). However, even with this new tool, the nervous system, with its densely packed neurons, looked just like a tangled mess when magnified (Ehrlich, 2022). A second invention was needed to birth modern neuroscience: Staining.

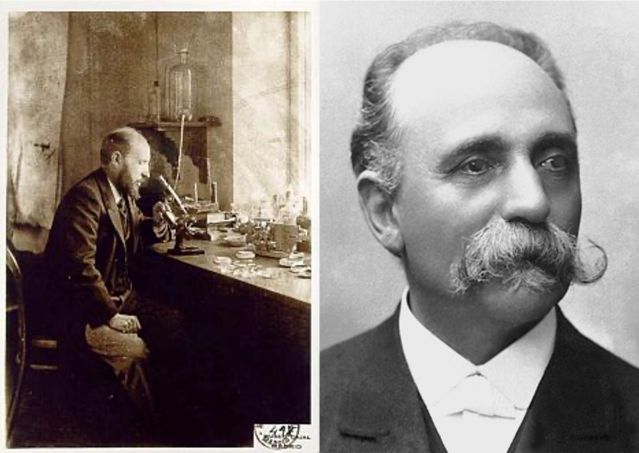

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Italian biologist Camillo Golgi set up a rudimentary lab in the kitchen of his apartment near the University of Pavia where he taught histology. His goal was to try to decode the structure of the nervous system (Bentivoglio et al., 2019). While experimenting with different methods, he soaked nervous tissue in a potassium dichromate solution for several days. When he subsequently added silver nitrate, some—but crucially, not all—neurons turned black: For the first time, an entire neuron with all its structures could be seen under the microscope (Bentivoglio et al., 2019). Golgi called this the “black reaction” and this method is still used today, now known simply as the Golgi stain.

The reticular theory

Understanding of anatomy and histology flourished after the invention of the microscope. The English polymath Robert Hooke (a contemporary of Isaac Newton and his fiercest rival) noticed that cork consisted of hexagonally shaped cells (Crouvisier-Urion et al., 2019). This came as a complete shock at the time but gradually morphed into cell theory, the notion that all living organisms are made up of cells, which form the foundational building blocks and the basic structural and organisational units. However, prior to Golgi’s black reaction, individual neurons could not be observed, and many anatomists believed that the nervous system formed an exception to the general cell theory. The German anatomist Joseph von Gerlach suggested that the entire nervous system consisted of a single net through which protoplasm could freely flow (Bentivoglio et al., 2019). He referred to this network as the reticulum because of its fine netlike structure, and this idea became known as the reticular theory.

Perception can sometimes be shaped by beliefs. This was true for Camilo Golgi, who despite having been the first to see entire neurons held so strongly to the reticular theory (albeit a revised version) that he saw neural axons not as ending in a synapse but as being fused to other neurons, forming a reticulum (Guillery, 2005).

The neuron doctrine

It took another leap to set neuroscience on a proper footing. The Spanish histologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal used Golgi’s staining method to extensively study the nervous system. His detailed drawings have not only led to countless discoveries but are still admired today for their scientific value (Cajal is often described as the father of modern neuroscience) and artistic beauty: His drawings have been shown at exhibitions and art galleries (Smith, 2018). In 1888 Cajal reported that neurons in the brains of birds were not continuous, suggesting that the nervous system is indeed made up of discrete cells, giving birth to a new theory, the neuron doctrine (López-Muñoz et al., 2006).

Golgi refused to accept this idea and the battle between the reticular theory and the neuron doctrine continued well after they both shared the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1906 (Grant, 2007). Although the neuron doctrine gained ground, it was not until the invention of the electron microscope that the issue was finally resolved for good in favour of the neuron doctrine (López-Muñoz et al., 2006).

References

Bentivoglio, M., Cotrufo, T., Ferrari, S., Tesoriero, C., Mariotto, S., Bertini, G., ... & Mazzarello, P. (2019). The original histological slides of Camillo Golgi and his discoveries on neuronal structure. Frontiers in neuroanatomy, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2019.00003

Crouvisier-Urion, K., Chanut, J., Lagorce, A., Winckler, P., Wang, Z., Verboven, P., ... & Karbowiak, T. (2019). Four hundred years of cork imaging: New advances in the characterization of the cork structure. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 19682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55193-9

DeFelipe, J. (2009). Cajal’s place in the history of neuroscience. In L. R. Squire (Ed.) Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Academic Press.

Ehrlich, B. (2022, Apr 1). The father of modern neuroscience discovered the basic unit of the nervous system. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-father-of-modern-neuroscience-discovered-the-basic-unit-of-the-nervous-system/

Grant, G. (2007). How the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared between Golgi and Cajal. Brain Research Review, 55(2), 490-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.004

Gregory, S. (2017). Chapter Two—Catesian illuminations: Transfers of light between the physics and philosophy of Descartes. In R. Lubashevsky & R. Milano (Eds.) Light in a socio-cultural perspective. (pp. 19-30). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Guenot, M. (2022, Dec 25). It's a myth that ancient Egyptians pulled mummy brains out by the nose — they likely scrambled them instead, says an expert who tried it. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/egypt-mummies-did-not-pull-brain-through-nose-2022-12

Guillery, R. W. (2005). Observations of synaptic structures: origins of the neuron doctrine and its current status. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 360(1458), 1281-1307. https://doi.org/10.1098%2Frstb.2003.1459

López-Muñoz, F., Boya, J., & Alamo, C. (2006). Neuron theory, the cornerstone of neuroscience, on the centenary of the Nobel Prize award to Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Brain research bulletin, 70(4-6), 391-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.07.010

Raviola, E., & Mazzarello, P. (2011). The diffuse nervous network of Camillo Golgi: Facts and fiction. Brain Research Reviews, 66(1-2), 75-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.09.005

van Middendorp, J. J., Sanchez, G. M., & Burridge, A. L. (2010). The Edwin Smith papyrus: a clinical reappraisal of the oldest known document on spinal injuries. European Spine Journal, 19, 1815-1823. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00586-010-1523-6

Pang, D. K. F. (2023). Ancient concepts of the mind, brain (and soul). Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/consciousness-and-beyond/202306/ancient-concepts-of-the-mind-brain-and-soul

Pang, D. K. F. (2023). How our neurobiology shapes our daily lives. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/consciousness-and-beyond/202312/how-our-neurobiology-shapes-our-daily-lives

Smith, R. (2018, Jan 18). A deep dive into the brain, hand-drawn by the father of neuroscience. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/arts/design/brain-neuroscience-santiago-ramon-y-cajal-grey-gallery.html

Walsh, V. (2017). Sensory system. Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.06867-X

Wollman, A. J., Nudd, R., Hedlund, E. G., & Leake, M. C. (2015). From Animaculum to single molecules: 300 years of the light microscope. Open biology, 5(4), 150019. https://doi.org/10.1098%2Frsob.150019