Mother’s day is upon us and it’s the first time I feel genuinely compelled to honor my mother, only this will be my first motherless mother’s day.

“Your first word was ‘no’ and you never stopped saying it.” This was my Mom’s characterization of me from the age of eighteen months to the day she died.

My poor mother. My sister, who is three years my senior, was easy-going while I was seemingly born to make her life difficult.

In my earliest memories, my mother’s fingers tightly gripped my arm, she pulled me along as I dawdled—daydreaming in the frozen food section of the grocery store, mesmerized by the rows of TV dinners. She had errands that needed to get done. Yet I was always doing something patently criminal, like licking S&H Green Stamps and sticking them to my forehead or getting bubble gum stuck in my long hair that I refused to brush. Plus, I was a picky eater. There were a few years when I refused to eat anything other than steak, butter, and grape juice. This kind of thing is now known as an eating disorder, but when I was a kid it was just called being a pain in the ass.

Our family stories revolve around what a good traveler my sister was, while I refused to eat local food during a trip to Mexico City, where I somehow managed to get sewage dumped on my head while watching a parade. Meanwhile, she was mortified and embarrassed by the “accidents” I had in ballet class. Later, we discovered I had urinary tract problems that needed to be corrected through surgery. I’m sure she didn’t intentionally ignore my underlying health problem, I’d simply overwhelmed her with my needs and contrarian nature.

When I was five years old, in what would prove to be a pivotal moment for our family, my parents packed up our wood paneled station wagon and drove north from Mobile to Wilmington. We arrived with only the suitcases that fit in the car; we didn’t have winter coats or the money to buy them.

We pulled up at my mom’s sister’s home and my mother took to bed in a nylon peignoir set. It wasn’t her bed, it was the twin bed with a Snoopy comforter in my cousin Shari’s bedroom, and she didn’t emerge again for several months. To borrow from Chekov’s The Seagull, my mother was “in mourning for her life.” My aunt and uncle folded my sister and me into their brood. My grandmother, Frances, slipped my aunt money every week to feed and clothe us.

This was the first move we made following my father and his dreams of getting rich—there was the insurance business, the radio station, the used car dealership, the restaurant, the movie distribution company, the silver mines, just to name a few of his schemes. Even though there were plenty of signs to the contrary, I was my father’s daughter, buying into his financial alchemy that one day he’d strike it rich and his characterization of my mother as no fun.

During these years of my childhood, my mother drove me to acting and singing lessons, but we fought constantly and were never close by any measure. My dad, a son of the south, was charming and charismatic. I was my father’s confidant and beard during the swinging ’70s when we lived in Miami Beach and enjoyed a nouveau riche existence. It wasn’t until yet another of his many bankruptcies that I woke up to the reality of our lives. My father’s failure to save money for my education was one thing, but the revelation that he hadn’t paid taxes in years disqualified me from financial aid. I had to drop out of college, leading me to many years of estrangement from my parents.

As angry as I was with my father, I was even more disappointed in my mother. I could chalk his irresponsibility up to a kind of narcissism, but I had no context for her passivity. How did she allow this happen? How could a mother leave her child so vulnerable?

But grandchildren bring family together. When I married and had my son nineteen years ago, my parents were attentive and visited several times a year from their home in Florida to my home in Los Angeles. As ever, my father was unfailingly the fun one and I kept my mother at arm’s length.

Five years ago, the house of cards came crashing down. Normally, I wouldn’t use such a cliché, but that’s what happened. My sister and I discovered that they had mortgaged their home so many times, there wasn’t much equity left, they had zero savings, no personal retirement funds and had not been keeping up with regular health care. My sister and I stepped in to untangle their finances, all while their health declined precipitously.

Ironically, it was this loss of yet another home that brought my mother and I close. My parents moved into a senior living facility that they could afford; and though it wasn’t perfect, it changed the dynamics of our family. At the onset, the transition was so stressful that I wound up spending so much time there that the staff referred to me as a part-time resident. My mother and I attended poetry class where we both enjoyed arguing the merits of Rudyard Kipling with the other residents. We went to exercise classes and were the most ambulatory of the residents. Holding hands, we performed our version of Rockettes’ line kicks. Both of us were mortified that the playlist for the class included Mel Torme’s version of “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” and we successfully campaigned for the addition of a disco number by K.C. and The Sunshine Band.

Amazingly, as she settled into this new environment my mother forged an identity apart from my father. She found buddies for trips to museums, concerts, and the ballet, reigniting her passion for the arts. She opened up to me about her life and I began to connect the dots.

My mother shared her childhood diaries with me, and a picture of a young woman with big little girl dreams emerged. Entries hinted at a desire to become an actress or a writer. I had no idea we had this in common and that she was thrilled to see me attain a career that she couldn’t muster the courage to pursue.

She’d earned a degree in sociology from the University of Delaware and had a brief tenure as a first grade teacher.

“It was horrible. I was on duty every single minute. I had to throw balls to them on the athletic field and sit with them at lunch. I didn’t have time to go to the bathroom. I was exhausted by three in the afternoon.” She lasted exactly two days.

Still, my mom was an excellent student. On the eve of deciding whether to earn a graduate degree, her parents asked her to represent their family at a wedding in Mobile; they could only afford one train ticket from Delaware. In Alabama, there were parties, teas, and dances held over several days; my mom was seduced by the southern hospitality as well as my dad, who was assigned to escort her during her stay. It was the first of a series of miscalculations—a lifetime of them.

She loved Mobile and she had confessed that for a long time she felt PTSD from having to return home. Clearly, the years of instability wore her down; and although I’m not a therapist, I’ve been in enough therapy to recognize that she never got the professional help that might have allowed her to break her cycle of depression and feel empowered. Her shame over our family’s tenuous financial position kept her isolated and her intimate friendships were few.

Finally, I saw her as a person separate from her role as my mother. I couldn’t make up a lifetime of failing to empathize with her, but we made our best memories there, in that unlikely place and just in time.

Maybe my parents were so codependent that it shouldn’t have been a surprise, but when I my father suddenly had a stroke and died, my mother’s health collapsed as well. My mother passed a few hours before the start of my father's memorial and my sister gave the speech in honor of my father, and I, the daughter who had fought with her for fifty years, gave the tribute to my mother’s life.

Now that she’s gone, I can’t imagine she’d want to read my collection of stories about our lives. She never really approved of my revealing so many personal details in my writing. I like to think that she’d be pleased to learn that I hear from readers who tell me they too have family secrets and how comforting it is to read that they’re not alone. I’ll never know for sure, but I suspect that despite her mixed feelings, she’d be as proud of me as she always was, even when she was unable to express it. I do know that unlike all the mother’s days of the past, my heart is filled with love and compassion for this mother that I only came to understand as she was leaving me.

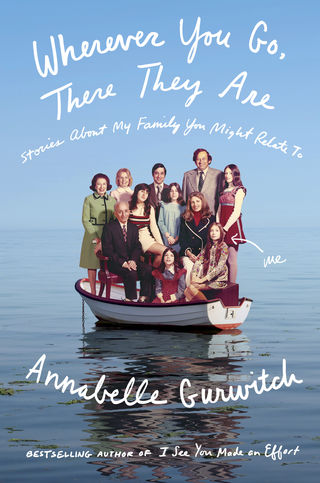

Annabelle Gurwitch is an actress and a New York Times bestselling author. Her most recent collection of essays WhereverYou Go, There They Are: Stories about my family you might relate to, has just been published.