Neuroscience

The Weak Link in the Democratic Process? The Human Brain

Voting relies on a skill set that is not among the brain's natural strengths.

Posted August 30, 2012

Examples of politicians who have transcended their elected posts through egregious levels of incompetence or criminal behavior abound. Perhaps Rod Blagojevich, the Illinois Governor who is currently in federal prison, comes to mind. But my personal favorite is Paulo Maluf, a Brazilian career politician who is currently an elected congressman1 and on Interpol’s Wanted Person’s list2.

Winston Churchill famously stated that “democracy is the worst form of government, except all those others that have been tried.” There are, of course, many complex socioeconomic, educational, historical, and political factors that contribute to the flawed execution of democratic systems of governance, but there is also perhaps a more fundamental reason: the human brain was not designed to vote. Like performing mental long division, or memorizing pages of a telephone book, voting seems to involve a recipe of cognitive operations that are not among the brain’s natural strengths. Deciding which candidates and platforms are more likely to guide a nation to long-term health and prosperity benefits from a rational analysis of complex concepts and data sets. Yet, studies show that our votes are influenced by a host of emotional and irrational factors. For example, one study presented subjects with the pictures of actual Gubernatorial and Senate candidates running in the 2006 elections. Based solely on the pictures participants were asked to pick the most competent candidate. Based on appearances alone the investigators were able predict election outcomes with a success rate of approximately 70%3.

There are undoubtedly many reasons why the human brain struggles to make optimal decisions in the voting booth. Here I will focus on two: the brain’s associative architecture and “delay blindness”.

Associative Architecture

Whether inside or outside of the voting booth, the strategy the brain uses to store information renders our decisions susceptible to irrational influences. The World Wide Web provides a helpful analogy to understand how the brain assigns meaning and stores semantic knowledge. The World-Wide Web is a network of many billions of nodes (webpages), each of which interacts (links) in some way with a subset of others. Which nodes are linked to each other is far from random. A website about diabetes will have links to other sites about diabetes, blood tests, diet, insulin and so forth. In other words we can learn a lot about what diabetes is, just by looking at the websites it is linked to. Information seems to be laid out in our own networks following similar principles: related concepts and words are linked to each other. So if I say dinosaur you probably think of big, extinct, Jurassic, or Tyrannosaur, because those concepts are probably connected within your circuits. But what determines which concepts are connected to each other? Experience.

The brain makes sense of the world by connecting the concepts that we are likely to experience at more or less the same time, that is, those that are associated with each other. Not coincidently, the building blocks of the brain, neurons and synapses, are perfectly suited to implement this associative architecture. Indeed a guiding principle in neuroscience is often phrased as “neurons that fire together, wire together”.

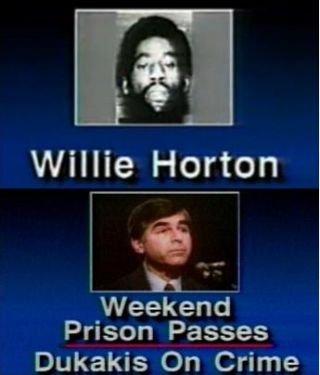

The associative architecture of the brain is among the brain’s most sophisticated features—it allows us to grasp context to a degree that still eludes the most powerful computers. There is little doubt, however, that the associative architecture of the brain also contributes to our knack for making irrational decisions, and is exploited in political marketing. For example, one of the most effective political ads in the history of American politics burned the association between the democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis and convicted murderer Willie Horton into the national psyche. The narrator cited how Horton assaulted and raped a woman after being released on a weekend furlough program during Dukakis’ governorship (the furlough program had been in place since Dukakis’ Republican predecessor, but Dukakis did veto a bill that would have ended the program for first-degree murderers).5,6 This emotionally charged and oversimplified association is seen by many as the key to Dukakis’ eventual loss. One factor that likely contributed to the effectiveness of this ad was the fact that for many Americans this was one of the first bits of information about Dukakis they were exposed to. To return to the WWW analogy: if one of the first links on the Dukakis’ page is to a murderer, its overall effect is much more significant than if it was one link among hundreds of others.

It is estimated that over a billion dollars will be spent in marketing in the current presidential elections. A significant portion of these funds will be used to create 30 second sound and image bytes based on simplistic associations, hyperbole, and emotionally-charged appeals that tap into your brain’s associative architecture.

Delay Blindness

Another factor contributing to our poor performance in the voting booth might be related to the brain’s inherent struggle with grasping time itself. The nervous system of most animals is exquisitely capable of picking up cause and effect relationships, as long as there is a short interval between the cause and effect. If a light goes on and off every time we hit a switch, we have no trouble establishing the causal relationship between action and effect. If, however, the delay was a mere ten seconds—perhaps it is a slow fluorescent light—the relationship is a bit harder to detect, particularly if in our impatience we have flipped the switch multiple times.

In his famous experiments the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov famously conditioned dogs to salivate in response to the sound of a bell by repeatedly presenting the bell and meat powder a few seconds apart. But if Pavlov had presented the meat powder 2 hours after each ring of the bell, there would be no chance the dogs would ever have learned the association, even though the ability of the bell to predict the occurrence of the meat would have been exactly the same. The longer the delay between two related events the harder it is to connect the dots. If cigarettes caused lung cancer within a week of one’s first cigarette, the tobacco industry would never have managed to develop into a mammoth multi-trillion dollar global business. Humans are probably the only species on the planet that have figured out the cause and effect relationship between sex and babies, but this does not mean we readily grasp how the present political, economic, and environmental conditions were shaped by policies put in place years or decades ago.

This “delay blindness” might have a number of profound implications for the democratic process. Consider that we seem to elect a candidate in part based on emotional judgments: Are she like me? Do he seem like nice people? Is he a regular “Joe”? As opposed to: Is she intelligent? Competent? Is there a reasonable correlation between the words coming out of his mouth and his actions? Do we use these same criteria when choosing a cardiac surgeon? I suspect most of us take a more rational and fact based approach when choosing a cardiac surgeon than when voting. It is easy to visualize the importance of having one’s cardiac surgeon be intelligent and competent—the relationship between skill and outcome is both obvious and fairly immediate. While the actions of our political representatives in many ways carry more weight than that of the surgeon—surgeons to not send thousands of young men and women off to war—the relationship between their decisions and our lives is much more convoluted and delayed.

If every time we voted we magically found out the next day whether we made the right or wrong choice we would probably all be better voters. The passage of time erases accountability and voids the standard feedback so critical to grasping cause and effect.

Our inherent temporal myopia partly explains the eternal campaign promise of tax cuts: it is much easier to envision the more immediate advantages of having more money in our pockets than the fuzzy long-term advantages of social programs and investments in education, research, technology, and infrastructure.

The human brain is the most complex device in the known universe, yet it is an imperfect one. The sooner we voters learn to recognize the natural flaws and limitations of the organ calling all the shots, the sooner we will be able to profit from the full potential of the democratic process.

For more on the how the brain's flaws shape our lives: