Suicide

Crisis Hostage Negotiation and the Impact of "Control"

How hostage negotiators help people regain control and achieve success.

Posted September 19, 2017

Often, when a person is in a crisis they feel like they have no control over their situation. This perception of life being out of control contributes to the person (or “subject” in crisis/hostage negotiation jargon) acting out of a combination of numerous negative emotions such as anger, fear, frustration, rage, despair, and sadness.

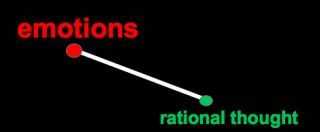

These overwhelming emotions and sensing their situation is hopeless prevents the person from acting rationally and being open to listening to others, being influenced by them or considering alternative options.

For a suicidal person, the subject might see completing suicide as their only option. For a barricaded perpetrator surrounded by police, they might believe their only option is to “never come out alive” or exiting their position in a hail of gunfire.

Not that crisis and hostage negotiators need a reminder, but this line of work is not easy. The above description is intended to generate empathy with the subject. Being able to “see things” through the eyes of another person is critical to eventually influencing them to gain their voluntary compliance. Remember that is the goal, as the alternative is involuntary compliance, which more than likely will involve some use of force.

In crisis situations, emotions can dictate a person's actions at the detriment of rational thinking.

If the subject feels as if they have no control, in order to attempt to successfully influence them to do what you want (while giving them the impression that they are making that choice themselves), you must help them regain a sense of control over their lives and their current situation. The Crisis Text Line calls this moving a person from a “hot moment” to a “cool calm.”

So how do you help a subject regain a sense of control over their situation?

One of the best tactics a crisis-hostage negotiator can employ, especially early in an interaction, is a collection of active listening skills. Active listening skills include a collection of micro skills that, among other valuable benefits, helps calm a person, de-escalate negative emotions, and allow them to share their perspective.

PRIME SOS is an active listening acronym taught to hostage negotiators across the country. It represents Paraphrasing, Reflect/Mirroring, Minimal Encouragers, Emotional Labeling, Summarizing, Open-ended Questions, and Silence. Read more on PRIME SOS [HERE].

When a person is talking (and you are actively listening to show you genuinely care), you let them tell their story, to share what it is that happened today and what it is that brought about their present crisis. Also, keep in mind, if the person is talking, they are not doing the things they were threatening to do.

A specific active listening tactic is strategic, open-ended questioning. Asking the subject what have they done in the past that helped them when they were in a similar situation (or any type of crisis) allows them to think about what has previously worked. This can get them to start contemplating other options and seeing that there are other ways out of this situation.

Having the subject reflect on their previous coping skills and getting them to think of other options returns that sense of control.

In addition to getting the subject to reflect on past actions that have helped them, looking to future actions can also help give them back control. An example could be letting them decide which hospital they will go to. This tactic also helps move from thinking about past, negative aspects of their life that they had no control over to now moving forward and having control over what happens next.

Finally, another important strategy crisis hostage negotiators use is called “stroking.” This involves complimenting the subject when they do something positive. Framing a statement in the following way demonstrates that they are making the choice on what to do (instead of someone else telling them what to do).

An example is, “Thank you, Bob, for choosing to lower the knife. I appreciate you doing that and continuing to talk with me. I’m interested in hearing more about…”

The above example gives the perspective that they are choosing to lower the knife and you are acknowledging that. The negotiator’s statement is short and concise while it concludes with seeking the subject to talk more about a topic the negotiator wants to know more about. A negotiator is still controlling things by guiding the conversation.

Although a subtle tactic, remember that often it is not one action that results in a hostage negotiator achieving their goal. Rather, it is the careful and effective use of numerous tactics that over time will result in repeated success—gaining voluntary compliance and ending the incident peacefully.

Acknowledging the impact that “control” can have, especially with a subject who feels they lack it over their own life and that mindset is contributing to his or her crisis allows the negotiator to develop a strategy to address it and move the subject from that “hot moment” to a “cool calm.” This then allows the subject to being open to the negotiator’s suggestions.

The above are just a few examples of how you can bring that sense of control back for the subject. This, of course, takes time and, like other skills, a negotiator must continually practice them in order to maintain their expertise.