Meditation

What Can We Learn From the Indus Seals?

The Indus seals may shed light on the early history of Hinduism and yoga.

Updated March 26, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Engraved with signs and images, the Indus seals were used to brand wares and sign contracts.

- The famous Pashupati seal seems to depict the Hindu god Shiva, sitting in a yogic pose.

- The Indus script, which remains undeciphered, bears witness to the early history of writing.

.jpg?itok=BPJc6Ie0)

In my previous post, I discussed the Indian subcontinent's first civilization and asked whether it might have been a utopia.

Of course, it is impossible to write about the Indus Valley Civilization without also writing about its famous seals.

These soapstone seals are a little over one-inch square and engraved with an image in the centre, and, on top, have signs that look like writing. Often, they have a pierced boss on the reverse to accommodate a cord.

The images are most commonly of animals such as bulls, elephants, and rhinoceros. But by far the most represented animal, on more than half of the seals, is a "unicorn" with what seems to be the body of a bull and the head of a zebra, crowned by a single, sigmoidal horn (Figure 1).

Some five thousand Indus seals have been found, some as far afield as Central Asia and the Middle East. From the large number of surviving sealings, it seems that they were used like signet rings, pressed into clay or wax to brand wares and sign contracts and receipts. Some seals may also have been worn as amulets or talismans.

The Pashupati Seal

Although animals, including bulls, dominate representations on Indus seals and other artefacts, there are no representations of cows. That said, there are some suggestions of continuity with Hinduism.

For example, female terracotta figurines have been found with red pigment on the hair parting, similar to the sindoor worn by married Hindu women.

Although carved some two thousand years later, the animals on the capital plinths of the pillars of Ashoka (d. 232 BCE) are of a similar style to those on the Indus seals.

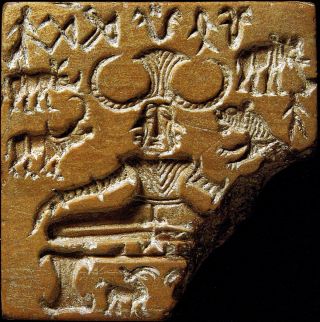

The so-called Pashupati (“Lord of the Animals”) seal, which is more elaborate than most, depicts a cross-legged figure surrounded by animals (Figure 2). Some have interpreted the figure, who has a horned headdress and possibly (it is hard to tell) three heads and a lingam, as an early depiction of Shiva, or proto-Shiva.

The Pashupati seal might also represent the earliest evidence of yoga, or yogic meditation, which has been an important inspiration and influence on modern approaches to mental health.

Deciphering the Indus Script

If we know relatively little about the Indus Valley Civilization, this is in part because the Indus script, like Minoan Linear A, remains undeciphered. It is also because the Harappans had no monarchs and cremated their dead, so that there are no rich burials like Tutankhamun in Egypt.

The Indus script is the earliest form of writing on the Indian subcontinent, with some inscriptions dating from the early Harappan phase, before 2700 BCE. After the demise of the Indus Valley Civilization, writing would not reappear in the subcontinent for another millennium.

Thousands of inscriptions have been found, mostly on seals, impressions of seals, and pottery markings. Most are very short, and none is longer than 26 signs. The signs are inscribed from right to left, and occasionally in boustrophedon (“turning ox”, alternating right-left, left-right from line to line).

Several hundred signs have been identified, although many are hapax, dis, or tris legomena that occur only once, twice, or thrice. Unless the signs are reducible, their sheer number suggests that the script is logosyllabic, with signs representing words as well as sounds—like Cuneiform, Han characters, and Mayan and Aztec glyphs. Certain strokes appear to be numerical.

Deciphering the Indus script is difficult for several reasons. First, the inscriptions are short. Second, there are no bilingual or digraphic texts like the Rosetta Stone. Third, we have no names, such as the names of cities, kings, or gods. Fourth, the signs might not even represent a language. And fifth, we do not know what this language might be, or even whether it is Indo-European, Dravidian, or something else.

If you enjoy a brainteaser, why not try to crack the code—and bring back a lost civilization?

Neel Burton is author of Indian Mythology and Philosophy.