I am interrupting my series on trauma to participate in an event organized by a few friends on Twitter. This post is my contribution to the online event Night of the Living Stim, a Twitter chat that we will be hosting on Thursday, October 17 at 6PM Central/7PM Eastern. The series on trauma will continue with my next post.

The other day, I felt strange phenomenon come over me. Suddenly, I felt a need to speak another language: Spanish. Experiences just like this are not at all unusual for me, but the reason for them might be surprising.

I have always liked language. I can remember my first exposure to a language other than English— in kindergarten. My teacher taught me a very simple phrase "Mi casa es su casa.” My house is your house. It stuck.

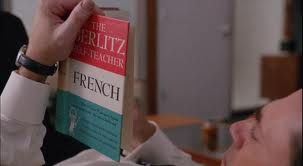

In the years since, language has remained the love of mine, and has carried me through a lot of difficult times. Berlitz books kept me company when, in the throes of severe social anxiety, I'd hide from my overzealous fifth grade teacher in a far corner of the schoolyard. I'd sit on the swings, the books on my lap, practicing unfamiliar phrases that delighted my tongue.

By the time I was in high school, language was a full-fledged special-interest. There are a lot of reasons for this, but there's one that I've only just begun to realize. Sometimes, for me, language is a form of self-stimulatory behavior.

What is that? As fellow autistic adult Ben Forshaw defines it, “It is a repetitive action that stimulates —provides—sensory input.” That sensory input serves as, “a form of negative feedback that allows me to regulate my senses. Negative in the sense that it modulates other sensory input and makes it easier for me to process: the input might be sound, touch — even emotion, which as I’ve described before has a large component of physical sensation.”

For Gavin Bollard, another adult on the spectrum stimming “allows you to concentrate on sensitivity and relax the thinking parts of the brain. In an Aspie, being able to stop thinking, even for a short while, is bliss.” For me, reasons for stimming can be complex and I don't always know why I do it, or when I do it.

When I go back and look at my growing up years, it sometimes hard to find examples of stimming in the traditional sense. While commonly known stims such as rocking could be observed in many of my family members, for me it took less obvious forms. I don't know if that has anything to do with gender or just my specific neurology.

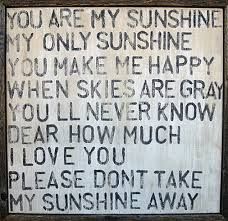

One particular form that stimming took for me was in mimicry, noisemaking and speech-like sounds—what Gavin refers to as “vocal stims.” I was fascinated by the way my voice could be made to sound so many different ways, and how different sounds generated different tactile feelings in my lips, mouth and tongue. I remember, for example spending hours in my backyard singing variations of the tune, “You Are My Sunshine”—replacing the first letter of each word with a particular letter of the alphabet.

As I slowly progressed through the alphabet, I would marvel how each change would change the way the song sounded to my ears, and how it felt to say. When it got two letters like “X” and “Z,” I’d get caught up in the vibrations pronouncing the words created. And, of course I got a bit of childish amusement from variations that resulted in words that were borderline naughty. Singing “Boo Bar By Bunshine” sent me into paroxysms of laughter.

Every bit of my environment seem to require in me a reaction. If we got on the elevator, I'd feel prompted to mimic its bell. If the neighborhood dog barked at me, I felt compelled to bark right back. And after living on a boat, I learned to call ducks with my mimicry of their “language”—a skill that benefited me socially more than you would think. I was the Dr. Dolittle of the first and second grade.

But the stim that sneaks up on me—but I didn't really think about as much—is the compulsion to repeat certain familiar words, phrases, and performances. It dovetailed a bit into my later interest in theater. But it began for me early, with my father's special interest in music.

Other kids would often get into Disney storybook records and the like, and I had a few of those…but for me, their appeal quickly paled. What did I need with them when I had my father’s concept albums? He'd bring them home and play them for me, acting out the stories as we went. The earliest one that I remember in the one that's stuck with me since, is the second side of the Small Faces album, “Ogden's Nut Gone Flake.”

The story, entitled “Happiness Stan,” is the story of a man who notices that half of the moon has disappeared and goes in search of it. A goofy little story, but one that managed to touch a couple of themes that resonated with the younger me—making sense of the phenomena of the world, being an outcast in the world that judges you as “not quite right,” and the simple pleasures of simply “twisting for awhile.”

But what made it fascinating to me was the fact that the story was not delivered in any English that was familiar to me, but rather what came to be known as “Unwinese”—courtesy of British comedian Stanley Unwin. Unwin was known for his particular brand of playfully corrupted speech, which feels to me at times almost to be Shakespearean. It was irresistible to me, and to some degree still is. Others find it near incomprehensible.

Nonetheless to this day, especially on a stressful day, I can often find repeating the story under my breath, Unwinese and all. And on very, very stressful days—there’s nothing that calms me more than just turning it on and spinning. Like many stims, it may be incomprehensible to others, but it's one of very few things that will calm the stress neurological system. It serves a purpose.

It's one of many strings of language or environmental sounds that I can find myself repeating—and I pick up new ones as time goes on. Ken Burns’ discovery of the Sullivan Ballou letter as part of his research for the Civil War series gave me a new one, and the various trabalenguas taught to me in Spanish classes make their appearances to. Nearly anything can be a source for a verbal stim.

We tend to look at repetitive speech is something slightly different than what is typically seen as a stim, but when you look at Forshaw’s description—for me speech sure fills the bill. The word “nada” feels physically very different to say than the word “nothing.” And how something feels to say is frequently what drives me to say it.

Fortunately for me, the words that feel good are frequently nonoffensive words. What is it like for people with a speech compulsion for whom that isn't the truth? How many people on the spectrum, especially kids, are caught by this phenomenon I wonder, and how does it affect them? And I also wonder how common it is…it's an aspect of the experience on the spectrum which is little talked about.

What I do know is that as odd as this particular brand of stim may be to some, it's given me a lot of comfort over the years. So, I'll share a little of it with you, with a little bit of legos, too. And, I’ll ask you—what’s your stim?

“Give me those happy days toy town newspaper smiles

Clap twice, lean back, twist for a while

When you're untogether and feeling out of tune

Sing this special song with me, don't worry 'bout the moon

Looks after itself.”

For updates you can follow me on Facebook or Twitter. Feedback? E-mail me.

My book, Living Independently on the Autism Spectrum, is currently available at most major retailers, including Books-A-Million, Chapters/Indigo (Canada), Barnes and Noble, and Amazon.

To read what others have to say about the book, visit my web site: www.lynnesoraya.com.