Trauma

A 2020 Vision for Expressive Arts Therapy

It’s time to see expressive arts therapy with 20/20 clarity.

Posted December 28, 2019 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Humans have historically used the arts in integrative ways, particularly within the contexts of enactment, ceremony, performance, and ritual. However, in the U.S., the arts and psychotherapy have developed somewhat in isolation from each other over many decades and within their own “silos.” There has been relatively little cross-fertilization between various arts-based approaches, largely because each has carved out a circumscribed domain and specific training standards.

But there are many important commonalities across these approaches that complement each other and are necessary for effective applications of arts-based strategies. I have spent more than 30 years studying how integrative arts-based forms of psychotherapy support health and well-being, particularly in work with trauma. To me, it is the integrative synergy of the arts, based on cultural traditions and current trauma-informed practice, that is requisite to addressing traumatic stress with most children, adults, families, groups, and communities (Malchiodi, 2020) (see my previous post on expressive arts as forms of culturally relevant therapy).

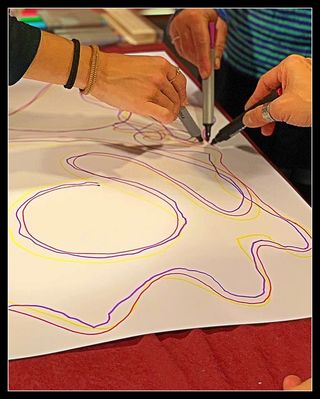

By definition, expressive arts therapy is a field of practice that emerged in the latter part of the 20th century. In contrast to the individual applications of specific art forms [visual art, music, dance, drama] in psychotherapy, expressive arts therapy is understood as the use of more than one art form, consecutively or in combination and depending on the individual or group goals. In other words, one art form may dominate, or multiple forms may be introduced in work with a child, adult, family, or group. This is referred to as a “multi-modal” approach, but I use the term “integrative” to emphasis the importance of combining expressive arts in purposeful ways to support psychotherapeutic goals.

As mental health and health care have shifted toward more integrative strategies to treatment, expressive arts therapy has gained the attention of a wide range of practitioners interested in applying sensory-based, action-oriented methods within their work, rather than one arts-based approach (for example, see this report from the National Organization for Arts in Health [NOAH], 2019).

Many practitioners in the field see expressive arts therapy as media-based; that is, it is defined by art form, such as the inclusion of movement, music, or drawing in a session. To me, it is first and foremost related to sensory-based expression, aesthetics (beauty, harmony, rhythm, resonance, synchrony, dynamic tension, and balance), and the process of imagination as key reparative factors.

In this sense, the approach is similar to integrative psychotherapists who rely on common curative factors among various schools of psychotherapy. This is the basic foundation for making decisions about how to introduce and integrate various art forms into individual and group sessions with the goal of enhancing health and well-being.

Letting the Senses Tell the Story

Neurobiology research has taught us that we need to “come to our senses” in developing effective psychotherapeutic approaches. In working with trauma, one quickly realizes that traumatic reactions are not just a series of distressing thoughts and feelings. They are experienced on a sensory level by mind and body, a concept now increasingly echoed within a variety of theories and approaches by trauma experts.

As early as 1990, psychiatrist Lenore Terr observed that individuals’ memories of trauma are more sensory, implicit, and perceptional than explicit or declarative. A few years later, van der Kolk (1994) noted that traumatic experiences may not always be encoded as explicit memory and may be stored as nonverbal, sensory fragments. More recently, many trauma specialists have embraced the idea that the “body keeps the score” (van der Kolk, 2014). This increased acceptance of the implicit nature of traumatic memories and a greater understanding of the body’s dysregulation as a result of distressing experiences have led to the development of many sensory-based, body-oriented, and “brain-wise” methods.

Possibly the most compelling reason for the use of the expressive arts in trauma work is the sensory nature of the arts themselves; their qualities involve visual, tactile, olfactory, auditory, vestibular, and proprioceptive experiences. Expressive arts, while whole-brain experiences, are also believed to access the right brain and implicit memory predominantly, because they include a variety of sensory-based experiences, including images, sounds, and tactile and movement experiences that are related to right-hemisphere functions. Current opinion about trauma supports the idea that trauma is encoded as a form of sensory reality, underscoring the idea that the expression and processing of implicit memories have an important role in successful intervention and resolution.

The qualities found in arts-based expression are thought to tap these memories of events (Malchiodi, 2012), releasing the potential of the senses to “tell the story” of traumatic experiences via an implicit form of communication. Trauma specialists also emphasize that sensory expression found in the expressive arts may make progressive exposure of the trauma story and expression of traumatic material more tolerable, helping to overcome avoidance and allowing the therapeutic process to advance relatively quickly (Spiegel et al., 2006).

Letting the senses tell the story is only one of the key characteristics of expressive arts within the context of psychotherapy. In subsequent posts, I will offer some deeper explanations as to why expressive arts therapy supports health and well-being, particularly in addressing traumatic stress.

Expressive arts therapy and related arts-based approaches have been too long misunderstood or dismissed as forms of diversion or activity-driven therapies. It’s time that these approaches are clearly recognized as part of the array of psychotherapeutic methods, and in particular, as forms of embodied awareness that take individuals beyond talking to implicit communication of what is often beyond words.

References

Malchiodi, C. A. (2020). Trauma and Expressive Arts Therapy: Brain, Body, and Imagination in the Healing Process. New York: Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2012b). Expressive arts therapy and multi-modal approaches. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Handbook of Art Therapy (2nd ed. (pp. 130–140). New York: Guilford Press.

National Organization for Arts in Health. (2019). About NOAH. Retrieved from https://thenoah.net/about.

Terr, L. (1990).Too Scared to Cry: Psychic Trauma in Childhood. New York: Harper & Row.

van der Kolk, B. A. (1994). The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 1(5), 253–265.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Penguin.