Cross-Cultural Psychology

Cancel Culture Will Kill Stand-Up Comedy

Humor relies on edgy violation.

Posted December 22, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Psychologists are coming to grips with what makes something funny.

- Humor principally relies on the presence of a benign violation.

- Emergent movements for moral righteousness risk eliminating a crucial part of the puzzle of comedy.

One of the cultural ideas dominating social discourse in recent years is that of cancel culture. This refers to the idea that people are having their freedom of expression curtailed and risk being silenced, censored, or (at worst) fired from their jobs for expressing particular views.

The reality of cancel culture is much-debated. High-profile examples of J.K. Rowling being canceled for her views on sex and gender jeopardize the legitimacy of the cancel culture notion (Rowling has published multiple books since the furore over her views first erupted). However, there have been some notable cases where cancel culture appears to have played out in the expected way, and where people have lost their jobs for expressing views that are unpopular, even when evidence-based.

In more contemporary examples, we have seen protests and (unsuccessful) demands for removing comedy specials from the likes of Dave Chappelle, Jimmy Carr, and Ricky Gervais in response to controversial sections of their most recent Netflix shows. This is interesting from a psychological perspective, and invites us to ask what makes something funny in the first place.

Comedy Relies on Benign Violations

Some may say that trying to boil constructs like humor down to a psychological theory takes the fun out of social life, but having a clear framework for matters such as these allows us to make predictions about how, when, and why people might find some things funny (and others not).

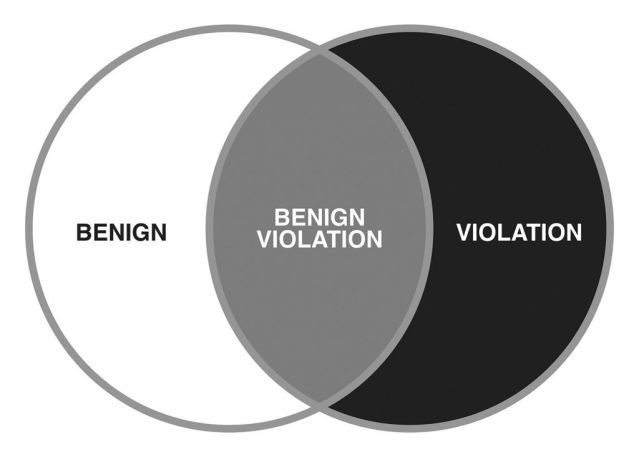

Peter McGraw, a psychology professor and lead for the Humor Research Lab (HuRL) based at the University of Colorado at Boulder, first wrote about the benign violation theory of humor with Caleb Warren in 2010 in an attempt to explain why people find particular things funny. It its core, benign violation theory posits that comedy inhabits the sweet spot between benign and violation. In the theory, benign is used as a stand-in for harmless, whereas violation refers to some contradiction of social norms or acceptability.

For something to be considered funny, then, the website of the Humor Research Lab suggests that three conditions need to be fulfilled:

- A situation represents a violation or threat

- The situation is benign or generally harmless

- Both of these perceptions of the situation occur simultaneously or in tandem

The example given by the team at HuRL is that of play-fighting. This behavior resembles something that is threatening in the form of violence (a violation of an accepted social norm), but is happening in a playful and consensual manner (making it benign).

The humor sweet-spot lies between the two extremes of benign and violation, which offer an explanation as to why some jokes (and the comedians who tell them) are perceived as not being funny. On the one hand, a joke might simply be benign. An example may be the dad jokes that proliferate on social media, those that elicit a sigh from many viewers. Such benign jokes without an edge (a violation) might be just perceived as boring by an audience.

On the other end of the model, a joke that represents a violation (endorsing a racist or sexist stereotype or other morally reprehensible attitude), without evidence of this being benign, might be perceived as being offensive, rather than funny.

Where Does Cancel Culture Fit with Benign Violations?

It is at this second end of the benign violation model that we might see cancel culture rear its head. When a joke is perceived as offensive, it is likely to elicit a range of negative emotions that include moral outrage and anger. Such emotions motivate a desire to engage in hypercritical behavior that is symptomatic of an attempted cancellation.

In previous posts for Psychology Today I have written about research showing how ideology can affect what we find funny. In one study, Dean Baltiansky and colleagues published a paper suggesting that their data demonstrated how those on the political right (conservatives, as are those who tend to score higher on the measure of system justification used in their work) are more likely find jokes about low-status groups disproportionately funnier than jokes about higher-status groups. However, a reanalysis of these data conducted by Harry Purser and I showed that this effect was driven primarily by liberals finding such jokes disproportionately less funny. Our commentary is due to be published in early 2023.

It is in the subjectivity brought about by ideology that cancel culture might be allowed to thrive. When viewing comedy through an ideological lens, it is possible to read offense into a joke where it is perhaps more benign in terms of its intention. An overperception of the violation, or an underperception of the benign nature of jokes, may be enough to bring about an emotional state that encourages a cancellation attempt.

What is likely needed is a serious social conversation about what is benign, what isn't, and how to respond to jokes (and comedians) that we do not find funny. This requires a degree of reflection that is seldom seen in contemporary polarized societies. It relies on us understanding our underlying theory of comedy, considering what we perceive as benign (and violating), and applying a reasonable person standard to the jokes and performers that we view. Without such reflection, comedy may be at risk of becoming so benign that it might eventually be difficult to find anything particularly funny.

References

McGraw, P. (2010). What makes things funny? [TEDx Talk]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysSgG5V-R3U

APA. (2021). What makes things funny? A conversation with Peter McGraw. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mt8CcykD4bo

McGraw, P., & Walker, J. (2014). The humor code: A global search for what makes things funny. Simon & Schuster.

McGraw, A. P., & Warren, C. (2010). Benign violations: Making immoral behavior funny. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1141-1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376073