Intelligence

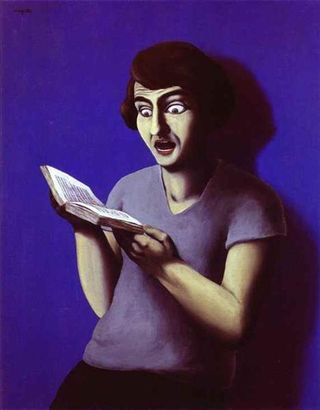

Don’t People Enjoy Reading Anymore?

Leisure reading is on a serious decline. Is that grounds for serious concern?

Posted July 6, 2018 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

“The share of Americans who read for pleasure on a given day,” data wonk Christopher Ingraham explains in the Washington Post, “has fallen by more than 30 percent since 2004.” His figures are based on material drawn from the latest American Time Use Survey from the Bureau of Labour Statistics. “In 2004,” Ingraham continues, “roughly 28 percent of Americans age 15 and older read for pleasure on a given day. Last year, the figure was about 19 percent.”

Who knows why there has been such a rapid decline. The easy answer, to blame the Internet, doesn’t seem to work. Leisure reading has been in decline since the 1980s, since well before the widespread adoption of distractions such as tablets, smartphones, and laptops. Is there an identifiable reason?

Christopher Ingraham again: “A long-term study of reading trends in the Netherlands points to a different culprit: television. From 1955 to 1995, TV time exploded while weekly reading time declined. Competition from television turned out to be the most evident cause of the decline in reading,’ the authors of that study concluded.”

Bad news for the modern brain? If you think so, then think about this: About two weeks after the American Time Use Survey, an article appeared from Norway on a decline in IQ scores. Oliver Moody, the science correspondent for The Times, reports, “Ole Rogeberg and Bernt Bratsberg, of the Ragnar Frisch Centre for Economic Research in Oslo, analyzed the scores from a standardized IQ test of more than 730,000 men who reported [in Norway] for national service between 1970 and 2009.”

What were the results? Moody again: “The vast majority of young Norwegian men are required to perform national service and take a standardized IQ test when they join up. The results, published in the journal PNAS, show that those born in 1991 scored about five points lower than those born in 1975, and three points lower than those born in 1962.” Bratsberg and Frisch are using a way larger sample than the 26,000 people of the American Time Use Survey. Their results are applicable not just in Norway, but also globally.

I’m not sure that anyone has tried to link this recent decline in IQ scores to the recent dip in leisure reading. But if you’re of a gloomy mindset like me, you can’t avoid wondering whether there could be some sort of a connection. But here’s one reason for hope, one reason why not to give in to the gloom and become worried.

Any reading may be a little helpful for your brain, I suppose, and for your intellect. But it’s very hard to believe that there’s anything particularly intellectually advantageous about reading books or magazines as a leisure activity. Seriously, does something like Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott’s excellent first novel, Swan Song, about Truman Capote improve your mind? Or does it mostly just please – not that there’s anything wrong with pleasure? There’s got to be limits to the benefits of reading, and I guess that these are set by the content of what it is you’re reading. Leisure reading doesn’t necessarily prime the IQ for greater accomplishments. So perhaps we shouldn’t be too alarmed by the finding of the American Time Use Survey.

Here’s a bit more on why we shouldn’t stress. Leisure reading is usually based on stories, true or false, historical or imagined. We humans seem to have an inexhaustible taste for them – it’s one of the key features that separates us from other animals. You just don’t see the great apes or small bonobos sitting around the campfire listening to stories, do you? If humans don’t get their stories from reading (like people from most generations), they’ll get them in other ways, especially from listening, but also from watching.

I’m not just referring to radio and video here. You could also get your story fix from a relative’s storytelling, or, once upon a time, from a communal storyteller or reciter (the sort of person that recited Homer’s stories to the ancient Greeks.) You could get it by watching some version or another of theatre (the ancient Greeks loved going to the theatre just like us). You could get it by watching or hearing about sporting performances. (The Greeks liked athletic games too). There’s a good story in a good sporting contest for sure. So, I wouldn’t place too much heed to the apparent decline in leisure reading. What really matters are the stories, and they still seem to be coming.

People today get their stories not just from books but also from TV, movies, and even audiobooks. Jack Malvern from The Times explains, “The value of the audiobook market increased from £12 million in 2013 to £31 million last year, according to the Publishers Association.” People are listening more and more, just like the Greeks did to Homer. And Michael Kozlowski, the Editor in Chief of Good e-Reader, reckons, “Audiobooks are the fastest growing segment in the digital publishing industry. The United States continues to be the biggest market for the audio format and in 2017, there was over $2.5 billion dollars in sales, which is a slight increase from the $2.1 billion generated in 2016. Michelle Cobb of the Audiobook Publishers Association stated, ‘26% of the US population has listened to an audiobook in the last 12 months’.”

Humans, you could almost say, have a strong evolutionary need for ingesting narrative. And I mean “ingesting” too, because this need seems to be strong like the need for food. Why evolutionary? Because storytelling is a human habit that won’t go away and it’s one that’s closely associated with being human. So maybe it’s a very good thing that we’re all so keenly pursuing one of the capacities that makes us distinctly human – listening to, watching, or, though less and less, reading stories. Maybe what matters is stories for leisure, not reading for leisure. And perhaps it doesn’t much matter what way you get them.

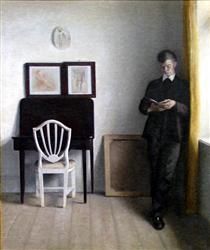

When you come to think of it, the mass market printing of books and of glossy magazines is something that really didn’t take off until as recently as after the second world war. Reading, or at least the possibility for the leisure reading of books is something that became “democratized” in the late 1940s and 1950s. The easy availability of leisure reading books is a pretty recent thing.

Now let’s go back to IQ, whose predicament I reported in my third paragraph. It’s taking a nosedive right now just like leisure reading. Should we worry about IQ as well as reading? To that, all I can say is this: Maybe IQ is a much more complicated measurement than you’d imagine and that we ought to be cautious about lamenting its decline too soon. Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking both had an IQ of 160.

But, as the John’s Hopkins psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison explains in her biography of the US poet Robert Lowell, “Nobel laureates James Watson, the discoverer of the structure of DNA, and Richard Feynman, the theoretical physicist, both tested with IQs of approximately 120.” Robert Lowell scored 121. Redfield Jamison concludes, “It seems that creativity and intelligence often diverge above an IQ of 120.” What can I say? If James Crick, Richard Feynman, and Robert Lowell could get by on 120, then where’s the worry? Now it would be good to read – or listen to – a story about that. You can try it for yourself with Kay Redfield Jamison's audiobook version of Robert Lowell’s life, Setting the River on Fire.