Genetics

More Evidence Suggests That Vegetarianism Is Mostly Due to Genes

New research dissects the nature and nurture of giving up meat.

Posted August 29, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Does nature or nurture explain why it is easy for some people to give up eating meat and nearly impossible for others?

- New studies have found genes play a surprisingly large role in meat preferences and the decision to become a vegetarian.

- Recent increases in vegetarianism show that "biology is not destiny."

The relative influence of genes and environment on human behavior is one of the most persistent, interesting, and divisive issues in psychology. The human penchant for eating animals is a good example. Clearly, culture has a huge influence on the amount of flesh people consume. The average American, for example, chows down on about 240 pounds of meat a year while per capita meat consumption in India is only 10 pounds per year. And your chances of being a vegetarian or vegan are nearly seven times higher if you live in India than in the United States (39% versus 6%). Further, cultures vary widely in types of edible animals (cats in Madagascar, termites in Tanzania).

Based on these cultural differences, you might think that nurture trumps nature when it comes to dietary decisions. But you would be wrong. Recent studies have found that differences in the types of meat people consume within cultures, and whether they eat animals at all, are highly influenced by genes.

Dissecting Nature and Nurture

Behavior genetics is the study of the relative influence of genetic and environmental factors on individual differences in behavior. Research on twins has proven particularly valuable in understanding how nature and nurture affect behavior. Identical twins share 100% of their genes while fraternal twins share, on average, 50% of their genes. If individual differences in behavior are largely determined by genes, identical twins should be more alike than fraternal twins. The degree of similarities and differences in pairs of identical compared to fraternal twins can be used to calculate a statistic called heritability, the percentage that individual differences are attributable to the influence of genes. If differences in a trait are almost completely genetic in origin—for example, eye color— heritability would be close to 1.00 (that is, 100% genetic). But, if environmental factors almost completely determine individual differences in a trait—say, religious denomination—heritability would be near 0 (or 100% environmental).

The Behavior Genetics of Giving Up Meat

In a pair of recent studies, Dutch researchers used twins to tease out the relative influences of heredity and environment on the decision to forego the consumption of meat. Their first study was based on the food preferences of 7,197 Finnish twins and their non-twin siblings. The researchers found that, in childhood, genes played a bigger role in individual differences in meat-eating among boys than girls. However, the reverse was true when their subjects grew into adulthood.

But their most important finding was the extent genes were involved in the decision to give up meat. Twin studies typically report that genes account for between 20% to 50% of individual differences in most aspects of human behavior. Yet among the Finnish twins, the heritability of vegetarianism was an astounding 75%.

Would the finding that genes are three times more important than environment hold up if the investigators studied twins in a different group? To answer this question, the team turned to the Netherlands Twins Register, a large ongoing study of Dutch twins. The lead researcher was Dr. Laura Wesseldijk, and their results will appear in the Journal of Food Quality and Preference. The researchers were primarily interested in genetic and environmental influences on vegetarianism (eating no meat or fish) and on pescetarianism (eating fish but not other kinds of meat). In addition, they obtained heritability estimates for abstaining from other types of animal flesh—pork, poultry, fish, and shellfish.

The participants were 8,196 adult twins and triplets, about evenly split between identical and fraternal twins. They were asked whether or not they ate various kinds of food. If participants indicated they did not eat a food item, they were asked why—for example, health reasons, allergies, weight issues, dislike, or beliefs (e.g., religion or veganism.)

The Results

The results were fascinating. First, when it came to the impact of genes on vegetarianism, the results replicated the findings of the study on Finnish twins. If one of the Dutch identical twins was a vegetarian, there was a 25% chance their sibling was a vegetarian compared to only 6% in the fraternal twins. In short, the pairs of identical twins were four times more similar in their meat avoidance than the fraternal twin pairs. This same pattern was true of the fish-eaters. Indeed, the team’s heritability analysis revealed that 76% of individual differences in vegetarianism and 74% of pescetarianism were due to the influence of genes.

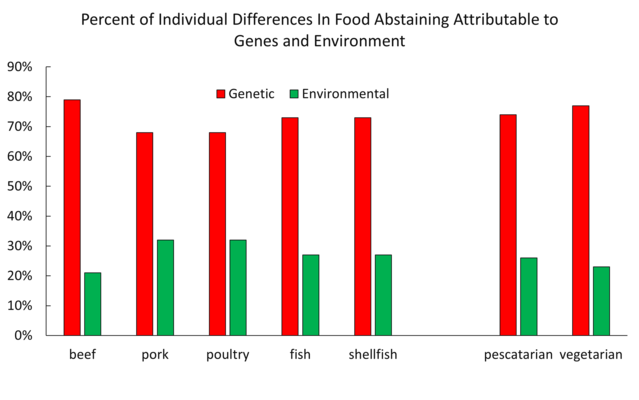

Second, the pattern of high genetic influence applied to decisions to abstain from other forms of animal flesh. The graph compares the percentage of individual differences in not eating beef, pork, poultry, fish, and shellfish that are due to genetic (red) and environmental factors (green). With every type of food, genes were, by far, the most important influence on decisions to forego types of meat.

Third, unlike individuals in the study who did not eat, say pork or chicken, most of the vegetarians and pescatarian twins were motivated to abstain from meat because of their beliefs (e.g., religion, animal welfare) rather than health issues or taste.

The Mystery of Genetic Influence on Vegetarianism

Two large twin studies have found that genes play a remarkably large role in the decision to give up meat. How this happens, however, is a mystery. One thing is certain: there is no “vegetarian” gene. Advances in genomics have shown that complex human behaviors are the result of the interactions of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of genes.

However, I can think of several ways genes might affect dietary decisions.

- Genes can influence taste sensitivity. Some people might find it easy to give up meat while others find it difficult because of differences in how food tastes to them. (See What’s the Deal With Vegetarians Who Hate Vegetables?)

- Do genes influence the ability to digest meat? It is possible that genetic differences in the ability to digest flesh could make meat-eating more unpleasant for some individuals than others. This would make it easier for them to eschew meat or perhaps motivate them to give up meat for health reasons. (While I think this idea is plausible, I could not find any research that supports it.)

- Genes can influence moral values. Behavior geneticists have found that differences in attitudes toward social issues such as capital punishment, racial discrimination, birth control, and euthanasia are roughly 50% attributable to genes. In a 2022 study, Michael Zakharin and Timothy Bates found that basic moral foundations including harm/care are influenced by genes. It is possible—indeed probable—that the whisperings of the genes impel some people to be more empathic and concerned about the welfare of other species. Thus they would be less likely to eat them.

A Few Words of Caution

The evidence is compelling that genes make it easy for some people to give up meat and nearly impossible for others (see Why Do Most Vegetarians Go Back to Eating Meat?). It is important, however, to keep in mind that estimates of heritability only apply to the populations that the subjects in the studies represent. Most of the individual differences in meat-eating among the Dutch are rooted in genes, yet culture is almost entirely responsible for the fact that per capita meat consumption is 20 times higher in the Netherlands than it is in India.

Yet, as Dr. Wesseldijk reminded me in an email, high heritabilities do not imply that biology is destiny. According to surveys by the Vegetarian Resource Group, the percentage of Americans who are vegetarian or vegan jumped six-fold between 1994 and 2022—from 1% to 6%. This impressive change in patterns of meat-eating was due to shifts in cultural attitudes, not changes in our DNA.

For a good overview of the most important findings in human behavior genetics, see Top Ten Replicated Findings In Behavior Genetics.

References

Çınar, Ç., Wesseldijk, L. W., Karinen, A. K., Jern, P., & Tybur, J. M. (2022). Sex differences in the genetic and environmental underpinnings of meat and plant preferences. Food Quality and Preference, 98, 104421.

Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Knopik, V. S., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2016). Top 10 replicated findings from behavioral genetics. Perspectives on psychological science, 11(1), 3-23.

Wesseldijk, L. W., Tybur, J. M., Boomsma, D. I., Willemsen, G., & Vink, J. M. (2022). The heritability of pescetarianism and vegetarianism. Food Quality and Preference, 104705.

Zakharin, M., & Bates, T. C. (2022). Testing heritability of moral foundations: Common pathway models support strong heritability for the five moral foundations. European Journal of Personality, 08902070221103957.