Cognition

Why Do Humpback Whales Sing?

Whale song may share more features with bat echolocation than with birdsong.

Posted September 15, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Previous analyses of whale song characterize it as a process in which singers produce sequences of repeating sound patterns, like birdsong.

- New analyses suggest humpback whale songs have a dynamic and flexible nature that signifies more sophisticated sound production.

- Whales seem to actively select and adjust acoustic elements of their songs in real-time, rather than just repeating stereotyped sound patterns.

- Instead of a display of reproductive fitness, whale songs may be a way for singers to actively explore their environments.

Whale song is largely considered to be a display of reproductive fitness, akin to the melodies produced by songbirds. But psychologist Eduardo Mercado III of the University at Buffalo thinks the dynamic nature of whale songs might signify a different function.

In their courtship displays, songbirds rely on the repetition of the same sounds sung in the same way. Mercado says whales are more like jazz musicians, constantly varying the acoustic qualities of their songs. In a new study published in the journal Animal Cognition, Mercado and his colleagues suggest the flexibility and sophistication of whale songs suggest the animals aren’t singing to attract mates but to actively explore their environments.

Singing Cetaceans

Male humpback whales are known for producing haunting songs, rhythmic sequences of sounds that can last for hours and be heard 20 miles or 30 kilometers away. The songs are heard most often during the winter breeding season but are also heard in the summer months. Humpback whales are one of the few mammals that produce new sound sequences after reaching maturity, and they seem to do it their whole lives.

Marine biologists have discovered that whales living near each other will sing similar songs, which differ from the songs of males in other groups, and that whale songs gradually change over the years. However, Mercado says, most past analyses of whale song have focused on collective changes in songs made at the population level.

“Researchers have cataloged the kinds of sounds whales make and how they have changed across the years to try to understand what this phenomenon is,” he says. “I was curious about what individual whales were doing when they sing if they repeat songs like birds or modify their songs in a way that would indicate flexible control.”

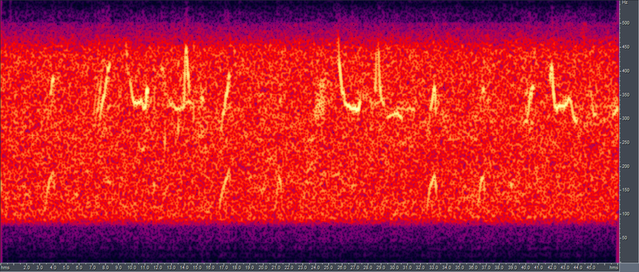

In the new study, Mercado and his colleagues analyzed song sessions produced by individual whales singing off the coast of Hawaii, recorded from a hydrophone on the ocean floor. The researchers thought that the ways in which whales vary their songs while singing could provide clues about how precisely song production is controlled and whether that control is voluntary.

Very Flexible Vocalizers

The analyses showed that individual humpback whales flexibly vary sound production and sound combinations across songs, rather than simply repeating stereotyped sound patterns. In this way, whale song is like jazz, says Mercado. Singing whales and jazz musicians are both capable of precise repetition, but they often choose to improvise.

“It turned out that whales produce these sounds very precisely,” he says. “Then sometimes during one of these very precise sequences, they would deviate and shift a sound’s duration or frequency in a predictable trajectory, suggesting these changes are controlled.”

In fact, Mercado and his colleagues say that singing whales may be intrinsically motivated to continuously vary multiple acoustic elements of their songs in precisely controlled ways.

“No other mammals that use vocal displays as part of reproduction have flexibility like this,” says Mercado. “Birds don’t have comparable control over their songs. I think humpback whales are probably doing something beyond just showing off and that people haven't really caught on to it yet.”

Singing to Themselves?

Although whale song is widely believed to be related to attracting females, there is no evidence that singing humpback whales are intentionally communicating information to other whales. If it’s not potential mates or rivals, who is the intended audience?

As Mercado and his colleagues write in their paper: “Singers appear to be actively constructing auditory scenes in real-time and constantly adjusting the acoustic properties of those scenes based on criteria and goals that have barely begun to be identified.”

“I think the driving force behind all of these changes is the perception of the singer, not the judgment of other whales,” says Mercado. “From his perspective, what is he perceiving that will lead him to change his sounds? He is a solo singer. It's not obvious why he would adjust at all.”

Mercado believes the flexibility of whale song is related to the way whales perceive sounds within their ocean habitats. For instance, he suggests that singing humpbacks may be trying to actively perceive the actions of other whales in the area using songs as sonar signals. If this is the case, the flexible modulation of individual sounds within songs may serve to enhance perception. Mercado suggests that in some ways, whale song may be more similar to bat echolocation than to birdsong. Echolocating bats are able to precisely control the timing and acoustic features of their vocalizations in real-time depending on the circumstances (changing their echolocation pulses in different habitats and during different tasks). Humpback whales may be doing the same thing.

“Part of the problem is that we hear whale song and it sounds mystical to us and we compare it to other songs we’ve heard,” says Mercado. “To the whales, it’s probably totally different. We just don’t know what’s happening inside the whale’s head when he’s singing.”

References

Mercado, E., Ashour, M. & McAllister, S. Cognitive control of song production by humpback whales. Animal Cognition (2022). Doi: 10.1007/s10071-022-01675-9.