Relationships

The So-Called Bad Dog: The Plight of Marginalized Nonhumans

Harlan Weaver offers a thoughtful discussion of pit bulls and humans.

Posted October 9, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Weaver argues that dog-human relationships are multidimensional and laden with stereotypes and prejudices.

- Nonhuman-human relationships shape and are shaped by nation, race, colonialism, gender, and sexuality.

- Structural violences that harm humans also harm the animals we live with.

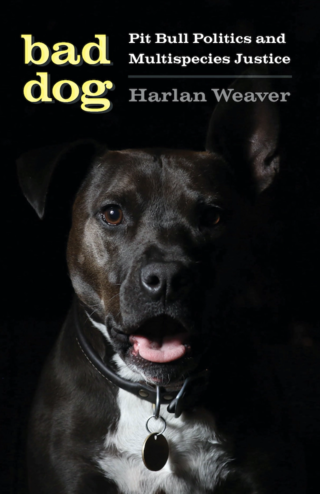

I recently read Dr. Harlan Weaver's book Bad Dog: Pit Bull Politics and Multispecies Justice.1 And I realized that my knowledge of dogs who are called "bad" is extremely limited. This description of his book is right on the mark, his book "explores how relationships between humans and animals not only reflect but actively shape experiences of race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, nation, breed, and species."

Why did you write Bad Dog?

Bad Dog began when I was at my most liminal during my medical transition, after I started testosterone and began to read as not-woman but not quite male. I noticed that when I was out on walks with my dog, Haley, a 65-pound pittie with ears clipped by her first owner, people we encountered would not mess with me in the way they would when I was by myself.

Conversely, people who encountered Haley with me—I’m white and gay—tended to see her as potentially friendly, which was not the case when they encountered her with her dog walker, a woman of color. These experiences made me realize that, at times, “my” gender was made possible by Haley, while her experience of breed was shaped by her connection (or lack thereof) to me. And while I was very aware of the stigma and legislation around pit bulls, not to mention the “I know it when I see it” designation of these dogs, this experience pushed me to explore what I term, borrowing from feminist legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, “interspecies intersectionality,” or the ways human-nonhuman animal relationships shape and are shaped by nation, race, colonialism, gender, and sexuality.

How does your book relate to your background and general areas of interest?

Prior to the project—funded by the NSF in its first year—I had volunteered at a number of shelters, which I expanded into ethnographic research in both shelter and rescue worlds. And while my background in feminist science and technology studies informed the histories of scientific constructions of racial difference via animality the book explores, I also teach and research queer and transgender studies. Queer-of-color critiques of heteronormativity as policing not just overtly gay-queer behavior, but also behavior by straight-reading folks of color—for example, Cathy Cohen’s writing about the Reagan-era rendering of the supposed “welfare queen” as a threat to be controlled by incentivizing marriage and long-term birth control or sterilization, aka eugenics—shaped my understanding of how the structural violence that harm humans also harm the animals we live with.

Who is your intended audience?

Folks in animal shelter and rescue worlds who are curious about how contemporary social justice movements connect to animal advocacy. People invested in understanding their dogs better, especially in terms of positive force-free training. And, of course, pit bull advocates.

What are some of the topics in your book and what are your major messages?

When I start my introductory classes, I always warn students that they’re in for what is called uncomfortable learning—learning that is uncomfortable not just because of its focus on power and oppression, but because it demands that we engage with our own complicity with those oppressions, however involuntary. The book’s first chapter is definitely in this category; in it, I examine the saviorism driving rescue and shelter work and ask readers to consider how colonialism and racism inform the idealized adoptive family-home central to these spaces. Knowledge politics are also key—ethology and training nerds will definitely enjoy the umwelt-inflected discussion of building an understanding of dogs through bodies, emotions, and bodily feelings. I also extend my thinking on human-animal identity production by examining NFL quarterback Michael Vick’s dogfighting case; the racialization by animalization directed at Vick post-conviction helps me get at points where co-productions of human-animal identities urgently need to be disrupted.

The book closes with a combination of policy recommendations and dreamings—concrete steps toward making shelters more socially just by, for example, removing them from the aegis of the police (common in many U.S. cities) join imaginings of what a world where shelters are not necessary would look and feel like. Throughout, I work to counter zero-sum thinking that regards care extended to animals as care taken away from humans; instead, I focus on how structures that are violent—both institutions and ways of thinking—harm humans and animals together.

How does your book differ from similar ones?

While I deeply appreciate Bronwen Dickey’s landmark writing, my own engages and theorizes race, gender, colonialism, and sexuality in ways that Dickey’s does not. More generally, there isn’t enough writing that connects what seem to be human-specific social justice questions to our relationships with nonhuman animals, especially when the relationships in question are about living together rather than eating—I hope my contribution can help change that.

Will people dispense with "bad dog" stereotypes and treat them with more respect and dignity?

Perhaps it’s impractical, but I am actually hopeful that we can build a world where “bad dogs” won’t emerge as such in the first place. I’m hopeful that as folks begin to better understand how movements for racial and indigenous justice connect to human-animal relationships, they will recognize how “bad dogs” become such through social factors—racism, classism, food insecurity, lack of access to veterinary care, lack of funds to fix fences or pay for training help, limited access to clean water, and so on—that are themselves structural violences.

While this recognition would certainly disrupt the pit bull = bad dog equation, it would also entail building better inter-species understandings on a broad scale—think how many fewer bites we’d have if going over dog and cat body language diagrams was a routine part of primary education. If we understand justice as practices and ways of thinking that dismantle structural violences and build better worlds, my hope is that, by questioning the class and racial norms that subtend the moniker “bad dog” and, more materially, by promoting practices such as free veterinary-behavior clinics or force-free shelter playgroups, we can begin to build towards a multi-species justice.

References

In conversation with Kansas State University's Dr. Harlan Weaver.

1) The book's description reads: Fifty-plus years of media fearmongering coupled with targeted breed bans have produced what could be called "America's Most Wanted" dog: the pit bull. However, at the turn of the twenty-first century, competing narratives began to change the meaning of "pit bull." Increasingly represented as loving members of mostly white, middle-class, heteronormative families, pit bulls and pit bull–type dogs are now frequently seen as victims rather than perpetrators, beings deserving not fear or scorn but rather care and compassion. Drawing from the increasingly contentious world of human-dog politics and featuring rich ethnographic research among dogs and their advocates, Bad Dog explores how relationships between humans and animals not only reflect but actively shape experiences of race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, nation, breed, and species. Harlan Weaver proposes a critical and queer reading of pit bull politics and animal advocacy, challenging the zero-sum logic through which care for animals is seen as detracting from care for humans. Introducing understandings rooted in examinations of what it means for humans to touch, feel, sense, and think with and through relationships with nonhuman animals, Weaver suggests powerful ways to seek justice for marginalized humans and animals together.