Dunning-Kruger Effect

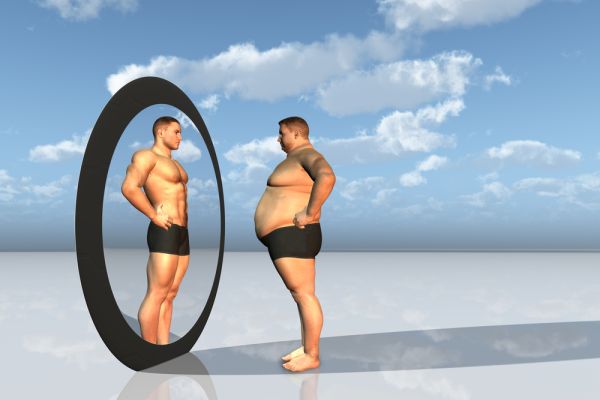

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people wrongly overestimate their knowledge or ability in a specific area. This tends to occur because a lack of self-awareness prevents them from accurately assessing their own skills.

The concept of the Dunning-Kruger effect is based on a 1999 paper by Cornell University psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger. The pair tested participants on their logic, grammar, and sense of humor, and found that those who performed in the bottom quartile rated their skills far above average. For example, those in the 12th percentile self-rated their expertise to be, on average, in the 62nd percentile.

The researchers attributed the trend to a problem of metacognition—the ability to analyze one’s own thoughts or performance. “Those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it,” they wrote.

Confidence is so highly prized that many people would rather pretend to be smart or skilled than risk looking inadequate and losing face. Even smart people can be affected by the Dunning-Kruger effect because having intelligence isn’t the same thing as learning and developing a specific skill. Many individuals mistakenly believe that their experience and skills in one particular area are transferable to another.

Many people would describe themselves as above average in intelligence, humor, and a variety of skills. They can’t accurately judge their own competence, because they lack metacognition, or the ability to step back and examine oneself objectively. In fact, those who are the least skilled are also the most likely to overestimate their abilities.

The Dunning-Kruger effect results in what’s known as a "double curse:" Not only do people perform poorly, but they are not self-aware enough to judge themselves accurately—and are thus unlikely to learn and grow.

If the Dunning-Kruger effect is being overconfident in one’s knowledge or performance, its polar opposite is imposter syndrome or the feeling that one is undeserving of success. People who have imposter syndrome are plagued by self-doubts and constantly feel like frauds who will be unmasked any second.

The Dunning-Kruger effect has been found in domains ranging from logical reasoning to emotional intelligence, financial knowledge, and firearm safety. And the effect isn't spotted only among incompetent individuals; most people have weak points where the bias can take hold. It also applies to people with a seemingly solid knowledge base: Individuals rating as high as the 80th percentile for a skill have still been found to overestimate their ability to some degree.

This tendency may occur because gaining a small amount of knowledge in an area about which one was previously ignorant can make people feel as though they’re suddenly virtual experts. Only after continuing to explore a topic do they realize how extensive it is and how much they still have to master.

One type of overconfidence, called overprecision, occurs when someone is exaggeratedly certain that their answers are correct. These individuals may seem highly competent and persuasive due to their apparent confidence. They are often driven by a desire for status and power and the need to appear smarter than the people around them.

Overestimation, another kind of overconfidence, refers to the discrepancy between someone’s skills and their perception of those skills. People who overestimate themselves frequently engage in wishful thinking with harmful consequences. If someone overestimates their capabilities, they may take dangerous risks and overextend themselves beyond their limits, like an athlete pushing themselves to the point of injury.

Anytime someone believes they are more skilled or knowledgeable than others, they are engaging in overplacement. This form of overconfidence can lead a person to take unnecessary risks (e.g., drive unsafely) because they believe they possess superior skills. Overplacement occurs most frequently in people with low abilities who lack the competence to judge their skill level accurately; it is associated with an egocentric perspective and narcissism.

To avoid falling prey to the Dunning-Kruger effect, people can honestly and routinely question their knowledge base and the conclusions they draw, rather than blindly accepting them. As David Dunning proposes, people can be their own devil’s advocates, by challenging themselves to probe how they might possibly be wrong.

Individuals could also escape the trap by seeking others whose expertise can help cover their own blind spots, such as turning to a colleague or friend for advice or constructive criticism. Continuing to study a specific subject will also bring one’s capacity into a clearer focus.

Ask yourself: Have you ever heard similar criticisms from different people in your life and ignored or discounted them? You may have experienced the Dunning-Kruger effect. Take a look at those areas in your life where you feel 100 percent confident. Acknowledge the possibility that you might not always be right, and you might need to acquire knowledge or practice more.

Question what you know and pay attention to those who have different viewpoints. Seek feedback from people you can trust who you know are highly skilled in your area of interest. Be open to constructive criticism and resist the impulse to become defensive. Don’t pretend to know something you don’t. Make it a priority to continue learning and growing.

Yes. Paradoxically, for many people, the more domain expertise they acquire, the less confidence they have. Experts have greater metacognition on their particular subject (they know what they don't know, so to speak), and are able to see complexities that a person with only a little knowledge in that area would overlook. As a result, they tend to be more aware of any knowledge gaps or weaknesses they may have.