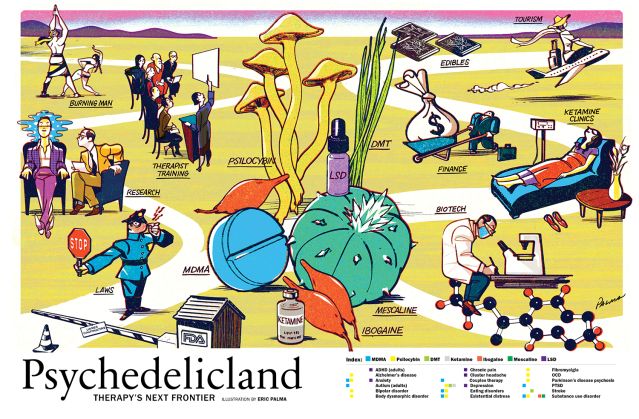

Why Psychedelics Are Therapy's Next Frontier

What psychedelics really feel like, and where they can take us.

By Psychology Today Contributors published January 3, 2023 - last reviewed on January 8, 2023

What Does The Psychedelic Experience Feel Like?

At the center of the psychedelic experience is the sense that you are not the center of it all—and that is liberating, exhilarating, and possibly life-changing.

By Gary Wenk, Ph.D.

Every moment of every day, courtesy of the neurotransmitter serotonin, your brain is processing sensory information, such as sights and sounds, and synthesizing it into your sense of self and your sense of place in the environment. You experience this self-referential awareness of a coherent whole as a “self” or “ego.” This sense of self feels rather fixed, static, but it is not. It’s constantly being updated by incoming sensory experiences.

The psychedelic experience feels as though this self-referential moment-to-moment updating of the ego has suddenly disappeared. The perception of our familiar self vanishes. The name given to this experience is ego death or ego dissolution. This distortion of our subjective experience of self is central to the psychedelic experience. People describe ego-dissolution as a diminished sense of self and an increase in the feeling of being at one with the universe, an experience felt as enriching.

However, my students also describe losing their sense of being grounded in the present, feeling disoriented, as though everything was unfamiliar. One student complained that she “lost all sense of myself.” This aspect of the psychedelic experience can increase feelings of anxiety and fear.

The psychedelic experience also includes an increase in emotional empathy, the ability to respond to another’s mental state. People report a greatly enhanced sociability, as though they have “taken off the mask they wear around others,” or that the personal “wall” that separates them from others has fallen. Because our ego separates us from others, ego-dissolution causes us to feel much closer to other people, whether we know them well or not.

Some psychedelics enhance visual imagery and the mixing of audio and visual sensory experiences so that colors might give off sounds. One student said that she watched the colors in a rug slowly rise up into trails of colorful smoke rings. Another had a conversation with her toaster one morning. Studies of rock carvings from Central America compared to drawings from modern subjects demonstrate that psychedelics produce geometric imagery of a consistent nature, regularly featuring latticework patterning, cobweb structure, and tunnel or funnel effects with spirals. Images tend to pulsate and move toward a center tunnel or away from a bright center. The brightness intensification most users report is due to the dilation of the pupils caused by the drug.

Psychedelics have another feature in common: They have few negative cognitive effects; intellectual or memory impairment is minimal. They do not cause a stupor or narcosis as alcohol and heroin do. And they do not produce excessive stimulation like that experienced with cocaine and amphetamines.

What gives most psychedelics, including the so-called “classics”—LSD, psilocybin, DMT, and mescaline— their many, and many powerful, attributes in common is that they act on the serotonin neurons and receptors in the body and brain. Although there are only a few hundred thousand serotonin neurons in the human brain, they influence the function of virtually every brain region and thus every aspect of normal waking consciousness. Not only is serotonin involved in processing sensory information, it also influences emotional responses, such as fear, excitement, and empathy. Further, serotonin neurons control heart rate, respiration, and the release of hormones by influencing the autonomic nervous system.

Not all psychedelics produce the same experience because not all psychedelics act on serotonin receptors; the psychedelic experience depends on which neurotransmitter receptors the agent is targeting. For example, extracts of the mushroom Amanita muscaria alter the function of acetylcholine neurons. Acetylcholine is involved in processing neural activity in an area of the neocortex devoted to vision. Users of this mushroom report that normal objects appear bigger or smaller than they truly are—an effect called macropsia or micropsia, respectively. Lewis Carroll incorporated the effects of this mushroom into Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Although they have been demonized in the United States since the 1970s, psychedelics, found naturally in a number of plants, have played a significant cultural role since ancient times, notably in religious ceremonies to facilitate communication with the gods. Typically, strict cultural rituals developed around the psychedelic experience. For example, only persons of high religious rank could consume mescaline, extracted from the peyote plant. Those of lesser status were accorded the honor of drinking the urine of these individuals.

Research into natural psychedelics and a growing array of synthetic variants has been accelerating over the past two decades. The commonly reported experience of increased social connectedness—enabled by a decreased sense of self and the dissociating of attention from personal concerns—and the development of wonder and appreciation for life give psychedelics considerable potential for human transformation in troubled times.

A View From The Lab

Psychedelics switch the brain away from existing beliefs toward sensory information—an act of potential benefit to people trapped in repetitive thought or behavior patterns.

By Paul Chadderton, Ph.D., and Caroline Golden, Ph.D.

Psychedelic compounds can produce intense, profound experiences and have shown promise in the treatment of PTSD and treatment-resistant depression, among other psychiatric conditions. Yet what is actually happening in the brain to produce psychedelic effects?

In a paper published in Scientific Reports in July 2022, we looked at the acute effect (or peak experience) of a 2mg/kg dose of psilocybin on the brains of awake mice, using electrodes that enable the recording of neural activity from single neurons, networks of neurons, and cumulative brain-wave activity. While there are different ways to estimate the human equivalent dose that would produce similar effects, we can say with confidence that this is a strong though still clinically relevant dose. We placed electrodes in the anterior cingulate cortex, an area of the brain known to be associated with emotional processing and internal awareness (interoception).

There is evidence that the anterior cingulate is key in the appraisal of fear- and anxiety-evoking stimuli—unsurprising given the strong functional connections that exist with the amygdala, one of the key emotion-processing centers in the brain. The anterior cingulate is part of the broader prefrontal cortex, critical in functions such as cognitive and emotional processing.

Psilocybin had a profound effect on brain-wave oscillations, which are thought to influence the communication patterns both within and among different areas of the brain. Brain oscillations can be divided into different bands, depending on their frequency, and different bands are proposed to serve different roles in brain communication. Slower oscillations, such as theta and delta waves, mediate communication among distal brain regions, whereas faster waves, such as gamma oscillations, are thought to represent local communication within specific regions.

Psilocybin significantly reduced slow-frequency oscillations and increased high-frequency oscillations, suggesting that the anterior cingulate becomes less influential over other brain regions, including the amygdala. In addition, neural activity in the anterior cingulate became more excitable and chaotic: Individual neurons became less synchronised with brain oscillations, consistent with the theory that psychedelics increase brain disorder, or entropy.

Our data suggest that psychedelics disrupt the influence of top-down brain modulation in favor of incoming sensory input, driving the brain to rely less on pre-existing beliefs and potentially enabling novel responses to incoming information. They support the REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics) model of psychedelics.

The switch in focus away from prior beliefs towards sensory information may be of fundamental significance for conditions such as depression. One debilitating aspect of depression is rumination, getting trapped in negative thoughts. Psychedelics may provide opportunities to break the cycle, to propel a person onto a better trajectory.

Psychedelics may also transiently return parts of the brain to a malleable, or plastic, state. Neural plasticity is typically greatest early in life, during childhood and adolescence. Once this window closes, learning ability slows. Psychedelics may reopen brain pathways to learning, enabling the weakening of negative memories and the formation of new, more positive patterning. Either or both actions could be highly beneficial in a variety of psychiatric conditions.

There are now many clinical trials not only of psilocybin but of other tryptamines, such as DMT and LSD, and more pharmacologically divergent psychedelics. Increased brain entropy has been shown with LSD, DMT, and ketamine. Not a true psychedelic but a dissociative agent, ketamine acts upon a different class of brain receptor—glutamate, not serotonergic 5-HT2A receptors. But it also shows promise as a rapid-acting antidepressant. Increased entropy could be reflective of a shared therapeutic mechanism, reachable via different neurotransmitter pathways.

Psilocybin, LSD, and DMT also all decrease functional connectivity within the default mode network (DMN), a group of interacting brain regions most active when the mind is internally focused. The DMN has a host of regulatory functions and is responsible for maintaining our sense of self, or ego, and of our place in the world.

The ego-dissolving effect of psychedelics enables people to see their thoughts and life from a less subjective, more objective standpoint—a feat achieved by experienced meditators as well (meditation has also been shown to reduce functional connectivity within the DMN). Ego dissolution may provide the link between psychedelic action and therapeutic effect in the brain.

A Return To Neural Childhood

There’s evidence that psychedelics pharmacologically restore critical periods of learning that usually close after adolescence.

By Hara Estroff Marano

You’ve no doubt heard the news. The world of psychiatric care is bracing for a major shake-up. Clinical studies of an array of psychedelic agents are underway for an astonishing range of conditions—from depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder to addiction, stroke, and anorexia, not to mention dementia and end-of-life terrors. The psychedelics, which promise lasting benefits with a shockingly short course of therapy, are substances that have been banned under federal statutes since 1970, deemed to have “no therapeutic potential.”

If MDMA passes a second round of Phase 3 clinical trials the way it did its initial ones, it is likely to be the first psychedelic available at a treatment center near you. In those trials, reported in Nature Medicine in June 2021, 67 percent of patients no longer qualified for a diagnosis after three treatment doses, each followed by three sessions of therapy to integrate the insights gained. And symptoms were still improving more than a year later.

“MDMA makes therapy especially effective,” says Rick Doblin, Ph.D., who in 1986 founded the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) as a nonprofit to produce pharmaceutical-grade MDMA and develop research protocols for the agents. Clinical trials of therapy with either inactive placebo or MDMA show that the psychedelic alone had a therapeutic effect size of 0.91—but combined with therapy it jumped to 2.1.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is marching toward approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PTSD in 2024. Depression, anxiety, and substance abuse will not be far behind. Although not a classic psychedelic, MDMA alters perception, and influences the release of serotonin and other neurotransmitters, especially the hormone oxytocin. “It’s the gentlest of all psychedelics,” says Doblin.

“If you combine these agents with really good psychotherapy, you can reach insights that turn life around,” says neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda, Ph.D. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP) works for so many indications, researchers believe, because the substances target the prefrontal cortex— the brain region central to so many neural operations and involved in so many disorders—and revamp its structure.

Drugs that induce the psychedelic experience share a molecular mechanism of action—they activate a specific receptor on neurons, the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor. They are, in the language of neuroscience, receptor agonists. But they act on a particular subset of neurons in the cerebral cortex, so-called layer 3 and layer 5 pyramidal neurons—essential for integrating incoming information across multiple brain areas to give us our experience of reality.

Psychedelics cause the pyramidal neurons to fire in a very disorganized way, messing up all the inputs, says Bryan Roth, M.D., Ph.D., a distinguished professor of pharmacology at the University of North Carolina and the head of its psychoactive drug-screening program. “Beyond that, the brain basically makes up a story,” he says, “with people interpreting the experience in very idiosyncratic ways.”

In 2009, Roth’s lab discovered that psychedelics target the pyramidal neurons to amp up the production of dendritic spines, vastly expanding synapse formation and the neurons’ capacity for incoming information. That is, they jump-start neural plasticity, an effect that has led some to view them as “psychoplastogens.” The neuroplastic effects are not only long-lasting but “we think they are responsible for the therapeutic actions,” says Roth.

Beyond mobilization of the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor, there is no unified theory of psychedelic action; the line from receptor fit to changed life can be only faintly sketched. “We have evidence from mice suggesting that these drugs turn on a whole gene transcriptional network related to synaptic plasticity,” says Roth, and that is “the physical substrate for maintaining the sense of meaning these drugs impart. It has to be encoded in the brain in some way.”

There’s also evidence that psychedelics stimulate hyperconnectivity between sensory brain regions as they relax connectivity in the self-involved default mode network. In doing so, they mimic neurodevelopment, pharmacologically creating the optimal brain state for environmental input to have enduring effects; in short, they reopen critical periods of learning that otherwise close after adolescence.

The opening is felt bodily, says Yehuda, the director of the Traumatic Stress Studies division at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Yehuda is conducting clinical trials of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy with MDMA for PTSD and psilocybin for depression. “Not everybody gets the miracle the first time,” she observes, “but what people do get is a sense that something can be opened up. They have to do a lot of psychological work after taking a psychedelic, but they approach it from the art of the possible.”

Therapy is essential, she believes, to help patients explore material that normally stays hidden “because there is a part of them that is protecting themselves from the wounds that might occur if they confront the distressing material. Therapy helps a person reach deeper to reorganize their consciousness for just a few hours.” As Doblin puts it, “Difficult is not the same as bad.” PTSD patients particularly are dealing with enormously challenging content. “MDMA makes the difficult expressible.”

Therapy helps patients metabolize the newly exposed information so they can begin recalibrating their psychological reality. The insight, Yehuda reports, “is not simply cognitive. It’s deeply experienced.” And it is not comfortably contained in current models of scientific explanation. But with new ways of seeing themselves and their relation to the world, patients can begin rewriting their story.

Whatever else the psychedelic experience is, it is intense. The perceptual effects are as emotional as they are sensory. The experience, says psychiatrist Rick Strassman, long a researcher of DMT at the University of New Mexico and the author of the newly released Psychedelic Handbook, is more real than real. In his studies of human volunteers given large doses of DMT, “almost all of them declared that what they just went through was more convincing, more true, more meaningful than anything they’d ever experienced.” It’s the intensity, he believes, that catalyzes therapeutic change—a “positive trauma” that changes one’s life.

Still, psychedelics are not magic pills. Because patients can approach memories and feelings they were unable to access before, they need good guides for interpreting the contents of their opened minds and integrating the insights into their life. And even before the drug is administered, patients need a soothing environment that conveys complete safety, thus minimizing anxiety, and preparatory therapy that sets expectations for the possibility of real benefit—elements that lead some researchers to contend that the real breakthrough of psychedelics is to supercharge the placebo effect.

The therapy now being designed to maximize the benefit of psychedelics differs significantly from current forms of psychotherapy. “It harkens more to psychodynamic models,” says Yehuda. “The idea is to follow the patient’s process and help them explore material that doesn’t usually come out. Therapists don’t have a clear idea of what’s going to happen but trust the medicine and the patient’s inner healing intelligence. They go with what’s on the patient’s mind in the moment. If you were trained 30 years ago, this isn’t new.”

Psychedelic-assisted therapy will require formal certification of all therapists who want to administer it, and training programs now springing up report no shortage of applicants. But the special conditions, labor intensity, and length of therapeutic sessions are costly and raise serious questions about who will have access to the transformation psychedelics promise.

As a result, a race is on to produce a virgin psychedelic—a molecule that can activate the 5HT2A receptor and ignite neuroplasticity without triggering hallucinogenic effects—safe for at-home use. It’s not clear yet whether subtracting the subjective experience still equals therapeutic effectiveness, but three major labs, including Roth’s, all with biotech support, are on the case.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of this issue.